March 22, 2023

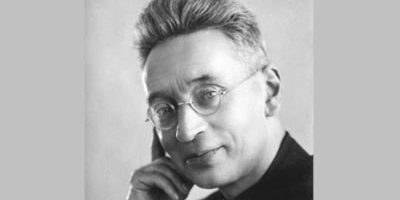

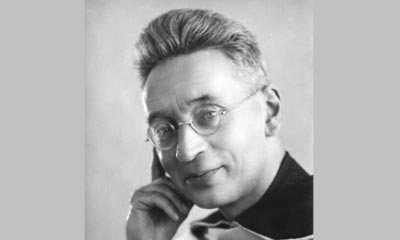

Saint Titus Brandsma

Dear Friends,

“Father Titus Brandsma appears almost as a contemporary figure, remarkable for his high moral stature,” said Pope John Paul II; “he was an upright priest, a university lecturer, an ecclesiastical consultant for the Catholic press, a writer and a journalist. His was a life spent for Christ, even unto heroic immolation in defense of truth and of the Catholic faith against the aggressions of totalitarianism, in the dark period of the Nazi invasion of Holland… Father Titus faced his ordeal with dauntless courage, of the same ilk as the clear serenity of his soul, moving from prison to prison amidst the harrowing atrocities inflicted on the inmates, and sealing his witness to Christ with his own supreme sacrifice in the concentration camp of Dachau” (Speech to faithful gathered in Rome for the beatification, November 4, 1985). He was canonized by Pope Francis on May 15, 2022.

His father, Titus Brandsma, along with his wife, Tjitje Postma, was a farmer in Dutch Friesland (northern Netherlands). They already had four daughters when, on February 23, 1881, Tjitje gave birth to their first son who was baptized Anno the next day. A little brother followed as the last child of the family. In this predominantly Protestant region, they were devout Catholics, attending Mass each day and praying together as a family every evening. The father was a member both of the parish council and the town council; he was also a cantor at Sunday Mass. Five vocations would blossom in this family (three of the girls and the two boys).

His father, Titus Brandsma, along with his wife, Tjitje Postma, was a farmer in Dutch Friesland (northern Netherlands). They already had four daughters when, on February 23, 1881, Tjitje gave birth to their first son who was baptized Anno the next day. A little brother followed as the last child of the family. In this predominantly Protestant region, they were devout Catholics, attending Mass each day and praying together as a family every evening. The father was a member both of the parish council and the town council; he was also a cantor at Sunday Mass. Five vocations would blossom in this family (three of the girls and the two boys).

A royal livery

Frail at birth, Anno would remain so all his life, but his intelligence and sensitivity were keen. His prodigious memory soon led him to the top of his class at the Franciscan school he attended. Although he had frequent stomach aches, that did not prevent him from skating when the river Maas was frozen. He was attracted to the religious life at a very early age. His particular devotion to Mary and his spirit of prayer drew him to the Carmelites, and he entered their convent in Boxmeer. There, discipline was harsh: the novitiate cells were heated only by a stove in the corridor. All the same, he wrote to his parents, “The spirit of the Carmel has captivated me.” On September 22, 1898, he received the religious habit, along with the name Brother Titus. In his eyes, the scapular of Our Lady of Mount Carmel was like the uniform of Mary’s guard of honor: “Neither talisman nor amulet, but a mark of honor and a royal livery.” He pronounced his first vows on October 3, 1899. But his poor health led him to be excused from some of the liturgical hours, especially from the night office. He was not yet twenty when he composed a three-hundred-page anthology of the works of St. Teresa of Avila, which his superiors deemed appropriate to publish.

In 1901, Father Hubert Driessen, a Carmelite Doctor of Philosophy, arrived from Rome to give a new momentum to studies in the Flemish province. Brother Titus tried to help the students who had difficulty understanding the master, but after three months, suffering from severe stomach pains, he was forced to take to his bed for some time. Before long, Father Driessen, who had been appointed Procurator General, returned to Rome. After his perpetual profession, Brother Titus went to the convent of Oss to study theology. Ordained a priest on June 17, 1905, he left to continue his studies in Rome, where he obtained a doctorate in philosophy in 1909. He was then appointed professor of philosophy and theology at the convent of Oss. Father Hubert Driessen, who had been named provincial for the Netherlands, entrusted him with the direction of studies for the Dutch Carmelites. In his low and somewhat monotonous voice, Father Titus succeeded in convincing the students that philosophy and theology are not purely speculative sciences, but that they allow for a better knowledge of God, and nurture the spiritual life.

In 1916, Father Titus started translating the works of St. Teresa of Avila into Dutch. As a member and secretary of the Catholic Union of Friesland, he translated the Imitation of Jesus Christ into Frisian (a Germanic language), and he was one of the driving forces behind the establishment of a chair of Frisian at the Catholic University of Nijmegen. In his daily life, he rendered every possible service, providing counsel to those who sought his advice, correcting articles for publication, and helping the homeless to find shelter. After the Great War, he introduced missionary weeks to finance the works of the Carmelites in Brazil. He preached missions in the Netherlands during the summer of 1921. But exhaustion and intestinal bleeding got the better of him, and he was forced to confine himself to his bed. However, his courage and his determination to recover allowed him to resume work in October.

Father Titus generously applied to join the Carmelite mission in Java, a Dutch colony at the time. But his superiors considered his presence more useful in the Flemish province, especially after his appointment in 1923 as professor at the new Catholic University of Nijmegen. There, everything needed to be organized, from the construction of a new Carmelite convent in the vicinity—of which he would incidentally be appointed prior—to the admission of students. He set up annual conferences to make the university and Flemish Catholic culture better known, even abroad. In the enthusiasm that accompanied the establishment of the feast of Christ the King by Pope Pius XI in 1925, he contributed to the raising of a giant statue of Christ the King in Oss.

Eyes and ears captivated

In 1926, he took part in the movement of the Apostolate of Reunification for the union of the separated Eastern Churches with the Roman Church, and he succeeded in founding a chair of Eastern theology in Nijmegen. He also showed sympathy for the persecuted Armenians and extended his charity to all non-Catholic Christians. His leadership at the university went hand in hand with his concern for secondary education and the founding of high schools. He made several visits to the Ministry of Education in order to obtain state subsidies for them. Elected rector of the University of Nijmegen in 1932 for three years, he proved to be an excellent administrator, capable of managing very delicate situations. The day after he left office, in 1935, he serenely returned to his lectures and apostolates. He also devoted himself to the ministry of the sacrament of Penance. He was soon invited to the United States for a lecture tour and showed a keen interest in minorities as well as in the Catholic press. During the journey, he stayed at the monastery of Niagara Falls: the beauty and immensity of nature immersed him in the mystery of God the Creator, and made him perceive his Love, while his eyes and ears remained captivated by the splendors of Niagara Falls.

In the midst of so many occupations, Father Titus always maintained an intense interior life. He strove to transform all his actions into prayer and worship: “Prayer is life,” he said, “not an oasis in a desert.” Pope Benedict XVI later expanded on the same thought: “True prayer consists precisely in uniting our will with that of God. For a Christian, therefore, to pray is not to evade reality and the responsibilities it brings but rather, to fully assume them, trusting in the faithful and inexhaustible love of the Lord. Dear brothers and sisters, prayer is not an accessory or ‘optional,’ but a question of life or death. In fact, only those who pray, in other words, who entrust themselves to God with filial love, can enter eternal life, which is God himself.” (March 4, 2007).

Father Titus wrote: “If only every human being wanted to live in the presence of God, and if we all lived in total dependence on this presence, the light of the Lord would shine so bright within us that we could but act in conformity with his laws. Men must find God and live in his light: that is what is meant by mysticism. The mystical spirit is not opposed to nature, on the contrary: is it not the calling of man to see God?” Having studied the mystics extensively, especially those of his Order and his country, he became the apostle of spiritual theology, focusing more on the teachings of the saints than on extraordinary manifestations. On the occasion of the beatification of St. Thérèse of Lisieux in 1923, he wrote: “We tend to expect something special from a saint, something out of the ordinary… Here, however, we witness a saintliness so prosaic and so ordinary that from the outside, we do not even see saintliness. But true holiness is precisely that.” Poverty was very dear to his heart: “Without poverty, a religious is only a Pharisee. Here in the Netherlands, more than anywhere else, we are too attached to all sorts of things, and we use all kinds of comfort.” But he took care to provide himself with adequate heating and any books he might need, in order to work well. His spiritual life also made him very attentive to others; he was prompt to offer a guest a cigar or a cup of coffee, although he himself would go without.

A forceful voice

In 1933, Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany. He achieved a spectacular economic recovery, but established a dictatorship based on an extremely harmful ideology, shaped by racism. Father Titus was one of the first to expose it. As early as 1934, in a pastoral letter, the bishops of Holland forbade Catholics to spread propaganda for Nazism. In 1935, a brochure entitled Dutch voices on the treatment of the Jews in Germany was published in Amsterdam. Professor Brandsma’s own forceful voice was among them. Father Titus’ stance did not go unnoticed in Germany: in Berlin, a newspaper published an insulting article entitled “This nasty professor.” In its wake, a smear campaign was launched in Nijmegen, accusing him of favoring communism. 1937 saw the condemnation by Pius XI, within a few days of each other, of Nazism (Encyclical Mit Brennender Sorge) and communism (Encyclical Divini Redemptoris). In Nazism, the Pope discerned a neo-paganism that must lead to apostasy and rejection of the one Church of Christ.

In his philosophy courses, Father Titus was not afraid to emphasize the perverseness of Nazi ideology, which stemmed from the philosophy of Nietzsche and was based on the will to power. In his book entitled: Spiritual Itinerary of Carmel, he wrote: “Neo-paganism may reject love, but history teaches us that, despite everything, we will be victorious over this neo-paganism through love. We will not abandon love. Love will win back the hearts of these pagans. Nature is stronger than philosophy. Let a philosophy reject and condemn love and call it weakness, the living testimony of love will always renew its power to conquer and captivate the hearts of men.” Pius XI declared: “The first, the most natural gift of love of the priest to his environment is the service of truth, and indeed of the whole truth: the unmasking and refutation of error, whatever form it may take, whatever disguise, whatever cosmetics it may wear.” (Mit Brennender Sorge, no. 44.)

Facing persecution

Despite Dutch neutrality in the European conflict, German troops invaded the Netherlands in May 1940. One year later, religious and priests were deprived of the right to run schools. The Archbishop of Utrecht asked Father Brandsma to speak in favor of freedom of education with the government department, in his capacity as president of the Union of Catholic Schools. Promises were made to him, but they would not be kept. In August 1941, Catholic schools were ordered to expel Jewish students. Titus declared: “The Church does not discriminate on the basis of race or belonging to a people. We cannot do otherwise than admit these children to our schools.” The Catholic press was also a bone of contention with the occupant. Father Titus, who had been appointed ecclesiastical advisor to Catholic journalists in 1935, declared that freedom of conscience must be upheld. On December 18, the Ministry of Propaganda informed the Dutch press that it was prohibited from refusing to publish articles produced by the National Socialist movement. On December 31, Titus wrote a letter to Catholic journalists urging them to disregard the order: any newspaper that agreed to insert such articles would lose its Catholic character. The Archbishop had a conversation with Father Titus advising caution: “They will arrest you sooner than me”—“I know” replied the Carmelite, “but I am freer to act than you.”

In January 1942, Father Brandsma travelled throughout the country at the Archbishop’s behest to meet the Bishops and the editors of Catholic newspapers, in order to convince them to implement the guidelines of his letter of the previous month. On January 15, the German authorities required all newspapers to publish two communiqués within two days. On January 16, the Archbishop threatened those who supported the Nazi movement with sanctions. Mindful of his shrewd and determined opposition, the Gestapo kept a close eye on Father Titus, “a small Brother, small but dangerous.” On January 19, two visitors presented themselves at his convent: they were Gestapo agents come to arrest him. Father Titus, who had just returned from giving a lecture, but who had been anticipating his arrest, presented himself: “Here I am!” They told him that they were to put him on the 6:30 p.m. train to Arnhem, and then began a thorough search of his room, which brought up nothing incriminating. As the train’s time of departure drew near, Father Titus exclaimed, “Gentlemen, it’s time to leave! Dutch trains are not used to being late, not even to wait for German policemen!” On their way downstairs, they met the director of the Catholic daily newspaper in Nijmegen, who had come to consult Father Titus: “I’m sorry, but I won’t be able to see you,” said the latter: “These gentlemen have come to arrest me… Better postpone the interview!” The whole community had assembled to see him leave the building. Father Titus asked the prior for permission to leave…

A dangerous element

On January 20, he was transferred to the political section of the Scheveningen prison in the Netherlands and underwent his first interrogation. Some bishops had advised him to put all the blame on them, but he had refused. Father Titus told officer Hardegen how faith gives the sons of the Church the strength to endure all sacrifices. The officer concluded that the Archbishop and Father Titus were the main architects of resistance to the orders of the party. The next day, the Carmelite gave his interrogators a written report on the incapacity of the Dutch Nazi party to influence Dutch society, which was so deeply rooted in Christian culture. The officer’s conclusion to his interrogation did not seek to hide his admiration for the Father’s determination, but it expressed the opinion that the religious should be kept in prison pending the decision of the higher authorities, as a dangerous element for the policy of the Reich. Father Titus remained in Scheveningen for fifty days. He transformed his prison cell into a religious cell: in the morning, he recited the prayers of the Mass and made spiritual Communion; then came personal prayer and the Hours of the Breviary. During his imprisonment, he wrote seven chapters of a biography of St. Teresa of Avila which he had undertaken, and which one of his confreres would complete after his death. Addressing the Lord, he said: “When I look at You, O Jesus, I understand that You love me as the dearest of Your friends!” And again, “You, O Jesus, stay close to me, I have never been so close to You. Stay with me. Stay with me, my sweet Jesus. Your closeness makes all things good to me.” Later he would confide: “I have rarely felt so happy.”

On March 12, he was transferred to the forced labor camp of Amersfoort: he must work nearly ten hours a day, digging up the frozen earth to lay out a firing range. However, he wrote to his confreres: “I have the opportunity to be in the open air and to talk with people I know. Everything is going well for me; don’t worry.” Poorly nourished, the prisoners rapidly lost weight. Father Titus suffered from dizziness and fainting spells; when dysentery set in, he was sent to the infirmary. However, he found the strength to support the morale of the other prisoners: they called him “Uncle Titus,” and everyone sought his company. Taking advantage of a certain tolerance on the part of the guards, he gave a conference to a hundred inmates on Good Friday on the significance of suffering: “Jesus is our example; He is our strength; His life and His Passion are the primary object of our contemplation.”

“In suffering,” noted St. John Paul II, “Father Titus knew that he was deeply connected to Christ. This is what granted him Christian serenity even in facing his tormentors, and gave him the strength to respond with love to the hatred he encountered. His solidarity with his fellow prisoners and his living faith—which made him pray even for his executioners—transmitted light and hope to all those who shared with him the cruelty and inhumanity of the camp” (November 4, 1985).

“That, we cannot tolerate!”

After his return to Scheveningen he was again interrogated at length on April 28 by Hardegen, who noted that the ordeal of hard labor had not shaken his resolve. The officer pronounced the following sentence: Titus “is not anti-German but opposed to Nazism, and that we cannot tolerate.” The Father shared his cell with two young Protestant prisoners. During their long conversations, he told them about his vocation. Together they meditated on the Bible and prayed, even for their guards. One of these, impressed by Titus’ irradiating joy, confessed to him. “We consider it a marvelous thing to have had Father Brandsma as a companion in prison,” the two prisoners later witnessed. “We are convinced that he was an extraordinary man and that he is now in heaven. He died a martyr for his faith.” On Saturday, May 16, Father Brandsma was transferred to Kleve, Germany, to a prison serving as a sorting station for deportees. Life there was more bearable. The prisoners were not condemned to work and enjoyed relative calm. There was a chapel where Titus could attend Mass and receive Holy Communion on Sundays and holidays. At that time his greatest suffering was that of hunger. On June 13, he was included in a group of prisoners to be sent to the concentration camp of Dachau. Every day, during the forced marches, and then in the camp, the guards beat him. Of his executioners, he went so far as to say: “They too are children of God, and perhaps something of it remains in them.” Declared fit for work despite his state of exhaustion, he had to walk two hours and work for eleven hours a day to landscape a park. On July 12, he wrote to his family: “I am well. Once again, with God’s help, I am adapting.” But his strength declined, and he struggled to follow the pace, which earned him new beatings, despite the protection of his fellow inmates. He spent 37 days in Dachau, where he often received Holy Communion because imprisoned German priests were able to celebrate Mass in secret. In five years, 2,600 clergymen passed through the camp, of whom 1,600 died. On July 26, 1942, a nurse killed Father Titus by injecting him with phenic acid.

On July 20, the Catholic bishops of Holland had published a letter condemning the Nazi persecution of the Jews. On the 27th, a decree from the Reich Commissioner for the Netherlands ordered: “All Catholic Jews will be deported during the course of this week.” St. Edith Stein was arrested and deported with her sister and thousands of other Jews to the Auschwitz extermination camp, where she was executed in a gas chamber on August 9.

After the beatification of Father Titus, St. John Paul II told the pilgrims: “Blessed Titus Brandsma used to say: ‘Whoever wants to win the world to Christ must have the courage to come into conflict with it.’ He himself lived in this way and thereby gave us an example. You too should have the courage, for Christ’s sake, not to conform to the world, to resist its beguiling temptations, and to walk faithfully in God’s ways alone.”