May 31, 2023

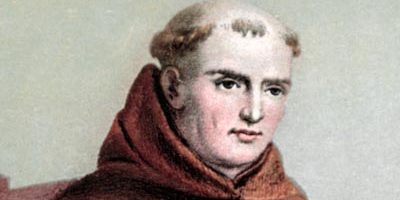

Saint Junipero Serra

Dear Friends,

During an apostolic journey to California in 1988, Saint John Paul II visited the tomb of Junípero Serra, who is now honored as a saint by the Church. The Pope described the significance of his pilgrimage as follows: “At crucial moments in human affairs, God raises up men and women whom he thrusts into roles of decisive importance for the future development of both society and the Church. We rejoice all the more when their achievement is coupled with a holiness of life that can truly be called heroic. So it is with Junípero Serra, who in the providence of God was destined to be the Apostle of California.” A statue of this humble priest may be seen in Washington, D.C. in the Statuary Hall of the Capitol of the United States.

Junípero Serra was born in 1713 in Petra on the island of Mallorca, the largest of the Spanish Balearic Islands. He was christened Miguel José. His parents, Antonio Nadal Serra and Margarita Rosa Ferrer, were peasants who could neither read nor write, but they were rich in faith and true charity. As a child, Miguel would hail passers-by with the pious local greeting, which he would later spread in America and which would survive him there: “Love God!” His parents decided that because of his delicate health, Miguel would never become a farmer or a stonemason, the two most common trades in the village. However, they perceived that he had intellectual potential and allowed him to attend the village school run by the Franciscans. He spent about ten years at the Franciscans as a schoolboy.

Junípero Serra was born in 1713 in Petra on the island of Mallorca, the largest of the Spanish Balearic Islands. He was christened Miguel José. His parents, Antonio Nadal Serra and Margarita Rosa Ferrer, were peasants who could neither read nor write, but they were rich in faith and true charity. As a child, Miguel would hail passers-by with the pious local greeting, which he would later spread in America and which would survive him there: “Love God!” His parents decided that because of his delicate health, Miguel would never become a farmer or a stonemason, the two most common trades in the village. However, they perceived that he had intellectual potential and allowed him to attend the village school run by the Franciscans. He spent about ten years at the Franciscans as a schoolboy.

Valuing the soul more than the body

When he turned sixteen, the young man asked to join the Order as a friar and took the name Junípero, in memory of one of the first companions of Saint Francis of Assisi whose simple and direct personality appealed to him. He joined the convent of St. Francis in Palma as a novice: he was enchanted by the silence, the Divine Office, and the lessons centered on the life of the founder. But to his great regret, his poor health earned him several dispensations, including exemption from rising at night (the friars would get up in the middle of the night to sing Matins), which led him to worry about his final admission. But his superiors valued the quality of the soul more than bodily strength, and received him into the Franciscan Order, in which he made his final commitment through religious profession on September 15, 1731. His physical ailments virtually disappeared from then on, so much so that during his life as a missionary he was able to cover extraordinary distances by running on foot. In Palma, Fray Junípero brilliantly completed a three-year course in philosophy, followed by another in theology. He was ordained a priest in 1737. His superiors directed him towards teaching, for which they considered him to have a natural gift. He became a professor of philosophy, and five years later, also of theology, at the Luliana University in Palma founded by Blessed Ramon Llull (1232-1315), and was highly regarded there. Yet this intellectual ministry proved insufficient to fulfill his aspirations, and in his spare time he went out to preach to the people all over the island.

The young friar had been struck during his studies by the accounts written by the missionaries of his Order who had settled in Latin America. At the age of thirty-five, Fray Junípero responded to a new call from God, which he had been patiently discerning in his heart, and obtained permission from his superior to go to “New Spain” (Mexico) as a missionary. After a stay of eight months in Cadiz, where he was held up by administrative and material setbacks, he embarked on a vessel bound for America with twenty fellow Franciscans as well as ten Dominicans in 1749. The voyage took 90 days; the water supply had been miscalculated and during the final days the passengers had to be severely rationed. “In order to be less thirsty, I resolved to speak less,” Brother Junípero would later explain. His courage and discipline were an encouragement to all. The ship called at Puerto Rico, in the West Indies, to stock water and supplies. A small hermitage provided shelter for the Franciscans, who used it to set up a mission for the time of the stopover, offering relief to the small number of priests living on the island. On his departure, Junípero was able to say that all the Puerto Ricans had gone to confession. On November 1, after a false start that almost ended in shipwreck, the boat set sail for the mainland. The crossing proved difficult because the ship was overloaded. On December 2, the passengers sighted the Mexican coast, but a violent storm drove back their ship. On the 4th, the crew mutinied against the captain and the pilot. The missionaries assembled to pray and agreed that if they were to survive this peril, they would especially honor the saint whose name would be drawn by lot. It turned out to be Saint Barbara, a fourth-century martyr who had her feast on that very day. They arrived in Vera Cruz on December 9 and they celebrated a Mass of thanksgiving on the following day in honor of Saint Barbara, to whom Junípero later dedicated a mission in California: it was to be the birthplace of the city of Santa Barbara.

5,000 miles on foot

While the rest of his companions made the journey to Mexico in horse-drawn carriages provided to them by the government, Father Serra, together with one of his Franciscan friars, decided to cover the 300 miles (500 km) journey to the city on foot in order to save time. On the way, he was bitten by an insect: this caused an inflammation to his leg which he ignored, resulting in an infected wound that would plague him for the rest of his life. They finally arrived at the capital and celebrated a Mass of thanksgiving at the shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe on January 1, 1750, after which they joined the Franciscan missionary college of San Fernando. Before embarking on his apostolate, Father Junípero Serra asked his superiors to find him a director of conscience: his priority always remained his own journey towards perfection. He was soon sent to a mission established in the Sierra Gorda mountain range, northwest of Mexico City (now in the state of Querétaro), among the Pames Indians, who were still pagans. Having rapidly learned the indigenous language, not without the help of the Holy Spirit, he translated the prayers and the catechism; he preached to the natives in their own tongue and taught them hymns. He worked to improve their living conditions by introducing them to agriculture, crafts and trade. Junípero was always to use the same methods of benevolent observation and adaptation to local living conditions. During his nine years in Sierra Gorda, Father Serra founded four missions (now listed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO), and travelled more than 5,000 miles (8,000 km), mostly on foot despite being handicapped by his injured leg: he always had to use a cane. By the time he was recalled to Mexico City, most of the Indians with whom he had been in contact were Catholic; their economic situation and social and individual lifestyles had improved.

In 1767, a decree by King Charles III of Spain ordered the expulsion of the Jesuits from all the crown’s domains, including those of the viceroyalty of New Spain, after he had been convinced by ministers and courtesans steeped in the “philosophical” mindset of the Enlightenment that the Jesuits were spreading the rumor that he was an illegitimate son. In Spanish America, it became necessary to replace the expelled Jesuits; to this end, the government called on the Franciscans. Father Serra was appointed administrator of all missions in Baja California (a peninsula in western Mexico). Shortly after his arrival at the mission of Loreto, he learned that Spain was seeking to colonize the coast of Alta California, which the English and the Russians also coveted, by establishing missions and military posts. This presented an opportunity that Fray Junípero had been dreaming of and praying for since a long time: to sow the good seed of the Gospel in a land that had not yet been tilled. He immediately volunteered “to erect the Holy Cross and establish its standard,” and was appointed head of the new mission.

At the beginning of 1769, Junípero Serra set off on his journey with gusto, although his infected leg forced him to travel by mule. When he arrived in San Diego (today in the United States, in the southern state of California), he was overjoyed. However, the situation was not rosy: on the way, some twenty soldiers had died of scurvy and the provisions had run out. Father Serra wrote to his superiors: “Let those who are to come here as missionaries not imagine that they are coming for any other purpose but to endure hardships for the love of God and the salvation of souls.” San Diego became the site of the first mission in California. The natives of this region lived in a very primitive way: they had no knowledge of agriculture, and their diet was based on gathering wild fruits and roots, hunting and fishing. They wore no clothes and, to protect themselves from the cold in winter, covered their bodies with animal hides, feathers and mud.

The greatest emergency: evangelization

When establishing a mission, Father Junípero always followed the same procedure. After finding a suitable place with plenty of water, he would build, in that order, a chapel for worship, a hut to house the brothers, and then a fortlet (a small fortified building) offering refuge in case of attack. Only then would he warmly receive the indigenous people whose curiosity led them to come to the mission. Once a sufficient degree of trust had been established, he invited them to settle in its vicinity. Fray Junípero never failed to bring farming equipment and livestock (especially horses) with him to share with the Amerindians on his explorations and foundational journeys. The Franciscans and their auxiliaries also taught them wood, iron, and stonework techniques as well as weaving. But the missionaries did not limit themselves to sharing the technical advances of European civilization with the indigenous people. Their ultimate goal was to bring the light of the Gospel and the salvific designs of Jesus Christ for each and every one of these people who had been until then prisoners of animistic superstitions, witchcraft and many vices. Conversions and baptisms abounded.

In his encyclical Redemptoris Missio (December 7, 1990), Saint John Paul II strongly emphasized the legitimacy of evangelization, as well as the Church’s duty to be missionary: “Proclaiming Christ and bearing witness to him, when done in a way that respects consciences, does not violate freedom. Faith demands a free adherence on the part of man, but at the same time faith must also be offered to him, because the ‘multitudes have the right to know the riches of the mystery of Christ-riches in which we believe that the whole of humanity can find, in unsuspected fullness, everything that it is gropingly searching for concerning God, man and his destiny, life and death, and truth… This is why the Church keeps her missionary spirit alive, and even wishes to intensify it in the moment of history in which we are living’” (no. 8). “The Church cannot fail to proclaim that Jesus came to reveal the face of God and to merit salvation for all humanity by his cross and resurrection” (no. 11). “Those who are incorporated in the Catholic Church ought to sense their privilege and for that very reason their greater obligation of bearing witness to the faith and to the Christian life as a service to their brothers and sisters and as a fitting response to God. They should be ever mindful that ‘they owe their distinguished status not to their own merits but to Christ’s special grace; and if they fail to respond to this grace in thought, word and deed, not only will they not be saved, they will be judged more severely’” (no. 11—Second Vatican Council, Lumen gentium). The same Pope, in the post-synodal apostolic exhortation Ecclesia in Asia (November 6, 1999), emphasized that “evangelization as the joyful, patient and progressive preaching of the saving Death and Resurrection of Jesus Christ must be (an) absolute priority.” For there is no other name under heaven given to men [than that of Jesus] whereby we must be saved (Saint Peter’s speech, Acts 4:12).

Always forward!

In 1770, Junípero Serra accompanied a Spanish overland expedition to Alta California, led by Gaspar de Portolá y Rovira. This journey led to the foundation of the “presidio” (military and civilian post) of Monterey, 50 miles (80 km) south of San Francisco, where Father Serra established the St. Charles Borromeo mission on June 3, 1770. The following year, in an attempt to avoid disputes with the governor of the presidio as well as to find better farmland, he moved the mission further south, closer to the Carmel River. This is where he established his headquarters for the remaining fourteen years of his life. Between 1770 and 1782, true to his motto “Always forward!”, he founded the first nine missions in Upper California, despite the opposition of the governor of California, Neves, a disciple of Voltaire. By 1794, they would comprise 4,650 Amerindians and 38 Franciscans. Twelve other Franciscan missions were founded between the death of Father Serra and 1823. In 1776, during another exploratory expedition and under the authority of Father Serra, Father Palou celebrated Mass in front of a hut and founded the mission of Saint Francis of Assisi, which became the starting point of the metropolis of San Francisco. Another mission, St. Mary of the Angels, was named after the shrine in Assisi where Saint Francis died. The present-day metropolis of Los Angeles was built around it.

Junípero and his brothers were sometimes in conflict with the civil authorities. In August 1770, Pedro Fages, governor of the presidio of Monterey, permitted a number of disorders: soldiers mistreated the natives and kidnapped indigenous women to use as concubines. As the governor had complete control over the mail, Serra decided to go to Mexico City himself to submit a “Representación” (complaint) to Viceroy Bucareli, demanding that the Indians be treated as human beings and proposing concrete measures to that end. The journey (2,000 miles [3,200 km] on foot) was further complicated by its secretive nature and the health problems of the sixty-year-old Father; it lasted three years. Father Serra’s “Representación” which has sometimes been described as the “Declaration of Rights of the Amerindians,” was accepted by the Spanish civil authorities and was quite widely implemented.

Obtaining more through gentleness

On November 4, 1775, Kumeyaay Indians attacked the San Diego mission, destroying all its buildings and killing Brother Luis Jaime. This aggression led to prosecution by the civil authorities; two years later, twenty natives were sentenced to death. Not all of them were murderers. Father Serra immediately wrote to the Viceroy and reminded him of a previous request: “If the natives, whether pagans or Christians, were to kill me or other Brothers, they should be forgiven.” Viceroy Moncada knew from experience that the Franciscans obtained more through gentleness than the soldiers through severity, and so he once again acceded to this request: the rebels escaped the death penalty.

Junípero Serra baptized over 5,000 Native Americans in California. After being granted a delegation of faculties by the Pope—a rare occurrence at the time—he administered to a further 6,000 the sacrament of Confirmation, an act normally reserved for the bishop. Sensing that his end was near, he set off on a final tour of his beloved missions. “My life is in California,” he wrote, “and God willing, it is here that I hope to die.” He returned to Monterey in a state of exhaustion on August 20, 1784, but he continued to pray, sing and dance with the natives. A doctor who examined him the next day warned him that his state of health was serious and that he should seek treatment. But the treatments administered to the patient were ineffective. On the night of the 27th to the 28th, Father Serra asked for the last sacraments. Together with the missionaries present, he recited the penitential psalms and the litanies of the saints; more than once, he tried to kneel on his prie-Dieu. He then received absolution with a plenary indulgence. In the morning, Father Palou found him prone, with an expression of profound serenity on his face, holding the large crucifix that he had been carrying with him since his arrival in the New World: Father Junípero Serra had given up his soul to God, virtually without agony. The news of his death immediately spread and crowds of people began to pour in. His corpse was religiously borne to the church. The laypeople obtained that the church remain open all night so that they could wake him. A solemn funeral was held the next day. The small local garrison and the crew of a Spanish ship lying in harbor would have been totally helpless if any disturbance had occurred, but all proceeded calmly and with great fervor. The relics were guarded to prevent them from being stolen by indelicate faithful. The relics of Saint Junípero continue to be venerated in Monterey-Carmel to this day, in the basilica of the mission he himself had founded.

Ahead of his times

Although Saint Junípero has been celebrated for more than two centuries by both religious and secular American leaders, his legacy has been challenged in recent decades by American revolutionary movements. The Franciscan, whom Pope Francis has called “one of the founding fathers of the United States” (in 1848, the US wrested Alta California from Mexico), is accused of having promoted colonialism and enslaved Native Americans. The uproar resulted in the savage removal of statues of Junípero Serra in Los Angeles and San Francisco by rioters in June 2020. In response to these senseless acts, the California bishops stated on June 22: “The historical truth is that Serra repeatedly pressed the Spanish authorities for better treatment of the Native American communities. Serra was not simply a man of his times. In working with Native Americans, he was a man ahead of his times who made great sacrifices to defend and serve the indigenous population and work against an oppression that extends far beyond the mission era.” José H. Gómez, Archbishop of Los Angeles and President of the American Bishops’ Conference, said: “I believe Fray Junípero is a saint for our times, the spiritual founder of Los Angeles, a champion of human rights, and this country’s first Hispanic saint. Saint Junípero came not to conquer, he came to be a brother. ‘We have all come here and remained here for the sole purpose of their well-being and salvation,’ he once wrote” of himself and his brothers.

Junípero Serra was canonized on September 23, 2015 by Pope Francis in Washington D.C. (USA). It was an “equipollent canonization:” because of the proven popular veneration for the Saint, the recognition of a miracle was not required. “Father Junípero Serra,” said the Pope in his homily, “He was the embodiment of ‘a Church which goes forth,’ a Church which sets out to bring everywhere the reconciling tenderness of God. Junípero Serra left his native land and its way of life. He was excited about blazing trails, going forth to meet many people, learning and valuing their particular customs and ways of life. He learned how to bring to birth and nurture God’s life in the faces of everyone he met; he made them his brothers and sisters. Junípero sought to defend the dignity of the native community, to protect it from those who had mistreated and abused it.”

At the end of her short earthly life, Saint Thérèse of Lisieux confided to a sister who was distressed to see her moving about with such difficulty in her convent because of her illness: “I am walking for a missionary!” Following her example, every one of us can participate in the mission, either directly or indirectly, by offering prayers, sacrifices and sufferings to God so that, in accordance with the command of Jesus Christ, the Gospel may be proclaimed with confidence to the ends of the earth (cf. Acts 1:8).