January 11, 2023

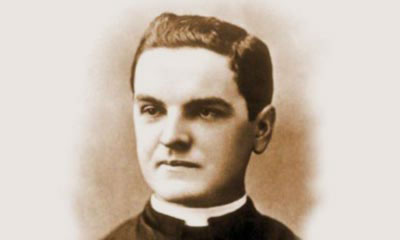

General Gaston de Sonis

Dear Friends,

It was December 2, 1870, just outside the village of Loigny (Eure-et-Loir, France), and night was falling. General de Sonis lay sprawled on the ground. He had been wounded during a legendary charge he had led at the head of the Pontifical Zouaves, preceded by the banner of the Sacred Heart. His heroic act saved the army corps under his command from total destruction. The injured soldier remained for the rest of the night on the battlefield, in freezing temperatures of 0°?F (-20°?C), yet he was fortified and comforted by Our Lady of Lourdes, whom he contemplated in spirit. “Thanks to Our Lady,” he later said, “those hours, though long, were not without consolation. I felt my sufferings so little that I have not kept any memory of them.” The General would receive no assistance until noon of the following day.

Louis-Gaston de Sonis was born in Pointe-à-Pitre (Guadeloupe) on August 25, 1825, into a family originating from Gascogne. His father, Jean-Baptiste, then a lieutenant in the infantry, had married a young widow, Marie-Elisabeth Sylphide—her maiden name was Bébian—who already had a daughter; together, they had five children. Young Gaston grew up in a loving family. He was deeply impressed by the magnificence of nature: “Lying at the bottom of the canoe… my head was turned towards the sky alight with glittering stars… God revealed himself to my soul for the first time at that moment. I must have been about six years old.” In September 1832, Mr. de Sonis returned to the French metropolis with Gaston, while the boy’s mother remained to care for her elderly father. “I embraced my beloved mother,” Gaston later said, “little knowing that it was for the last time.” She was to die in Pointe-à-Pitre in 1835. Gaston, who never returned to Guadeloupe, made his first Holy Communion at the age of ten: “I have always firmly believed that this first Holy Communion was the blessing of my life,” he wrote. He was enrolled in the College of Juilly, run by the Oratorians, and spent three years there, distinguishing himself by his elegance, his piety, his sincere camaraderie and his enthusiasm. Despite a first failed attempt, Gaston was admitted to the military school of Saint-Cyr. In September 1844, his father fell seriously ill. The young man’s faith had waned and he tried to prevent his father from being visited by a priest, fearing that he would lose the will to live. But thanks to his daughters, the ailing man was able to receive the sacraments before he died. Father Poncet, a Jesuit, comforted his children. “He spoke to us for a long time,” Gaston recalled, “and every word he spoke resonated… From the start, my heart was opened wide… When he left us, Jesus Christ had regained possession of my heart.”

Louis-Gaston de Sonis was born in Pointe-à-Pitre (Guadeloupe) on August 25, 1825, into a family originating from Gascogne. His father, Jean-Baptiste, then a lieutenant in the infantry, had married a young widow, Marie-Elisabeth Sylphide—her maiden name was Bébian—who already had a daughter; together, they had five children. Young Gaston grew up in a loving family. He was deeply impressed by the magnificence of nature: “Lying at the bottom of the canoe… my head was turned towards the sky alight with glittering stars… God revealed himself to my soul for the first time at that moment. I must have been about six years old.” In September 1832, Mr. de Sonis returned to the French metropolis with Gaston, while the boy’s mother remained to care for her elderly father. “I embraced my beloved mother,” Gaston later said, “little knowing that it was for the last time.” She was to die in Pointe-à-Pitre in 1835. Gaston, who never returned to Guadeloupe, made his first Holy Communion at the age of ten: “I have always firmly believed that this first Holy Communion was the blessing of my life,” he wrote. He was enrolled in the College of Juilly, run by the Oratorians, and spent three years there, distinguishing himself by his elegance, his piety, his sincere camaraderie and his enthusiasm. Despite a first failed attempt, Gaston was admitted to the military school of Saint-Cyr. In September 1844, his father fell seriously ill. The young man’s faith had waned and he tried to prevent his father from being visited by a priest, fearing that he would lose the will to live. But thanks to his daughters, the ailing man was able to receive the sacraments before he died. Father Poncet, a Jesuit, comforted his children. “He spoke to us for a long time,” Gaston recalled, “and every word he spoke resonated… From the start, my heart was opened wide… When he left us, Jesus Christ had regained possession of my heart.”

At Saint-Cyr, the young man faced a struggle to maintain his faith in a rather irreligious environment. In 1846, he chose the cavalry at the Cadre Noir of Saumur. Around this time, he spent a day of recollection at the Abbey of Solesmes, which had recently been restored by Dom Guéranger. He did not have a monastic vocation, but promised to refuse nothing to the Divine Master: “One must not bargain with God,” he was wont to say. In April 1848, he was appointed second lieutenant in the 5th regiment of Hussars, in Castres. In Saumur, unaware of its condemnations by the Church, he had been initiated into the Freemasonry, which had been presented to him as a charitable society. In Castres, he realized to what extent it was fighting against the Christian Revelation. During a meeting, he stood up politely and explained: “I can stay no longer in an assembly where the religion I profess is being attacked… I took a wrong turn; from now on do not count me as one of your own.”

A treasury of bounty

The young officer was introduced to Anaïs Roger, whom he married on April 18, 1849, in Castres. “Truly, we had but one heart and one soul,” Anaïs would later write. “The heart of my dear Gaston was a treasury of bounty and tenderness, with exquisite sensitivity, while his most virile soul was unusually firm.” Gaston was soon transferred to Brittany, and then to Paris. The young lieutenant was carried away by the sermons of Father Lacordaire, a Dominican, in the cathedral of Paris: “I emerged from Notre-Dame overwhelmed by the love of God and the Church.” In October 1851, he moved to Limoges with his family, which counted two children at the time. Gaston went to Mass every day at five in the morning. He would often make the Way of the Cross in church in the evenings. He enrolled in the conferences of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul, and organized carousels of Hussars or collections of linen for the benefit of the poor.

Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte re-established the Empire in 1852, and asked for the people’s approval. The army was in favor, but Sonis, remembering the role that the prince had played in the insurrection of the Romagnes against Pius IX, spoke out in the negative, not without risk to his career: in his eyes, honor must take precedence over personal interest. After the plebiscite, however, he granted his fidelity to the emperor. He and his wife often went riding on horseback. One day, unseated by a sharp deviation of his mount, he fell on a fence and seriously injured his kidneys. He was given the last rites; thank God and the care of his wife, he survived. The ordeal transformed his life into a long dialogue with God, and at the same time he became more attentive to others. In Limoges, he established nocturnal adoration of the Blessed Sacrament. When invited to a salon where a table was being turned during an improvised seance, he refused to join, and sat down in a corner, reading his newspaper. From that moment, the table remained motionless…

Depriving oneself of one’s wants

and even of one’s needs

Sonis’ spiritual life was based on firm discipline: “Although I was a soldier, married and father of a large family,” he later said, “I knew little of the world; I abstained from entertainments, and if I have earned the reproach of having lived more or less like a monk, I bless heaven for that…” His wife testified: “My husband sought to encourage me to walk with him in more perfect ways, for he loved my soul more than anything in this world. I am ashamed to say that I sometimes experienced a kind of jealousy over his godliness. My excellent husband would gently rebuke me, telling me that I should not be jealous of the good Lord, and that the more we loved Him, the more lasting our mutual attachment would be.” Gaston gave his children a strong Christian education, encouraging them to have a good heart: “Let my children be generous to the poor. Alms purgeth away sins (cf. Tob 12:9). We must know how to deprive ourselves of everything we merely want, and sometimes of what we need, in order to give ourselves the joy of giving alms.” As an officer, he was attentive to his men, giving them advice and sometimes even solace. His example led many of them back to religious practice.

In May 1854, Sonis was promoted to the rank of Captain in the 7th Hussars; he had to go to Algeria. This renewed separation from his family broke his heart. The contrasting landscapes of the Algerian coast, Kabylia and the Atlas Mountains filled him with enthusiasm: “How small I feel in the presence of this gigantic natural environment! Never better have I sensed my nothingness, but at the same time, never have I had better hope in the infinite mercy of this God who has made us so small only to stir us to rise up to Him.” Yet he suffered from encountering only impiety among the colonists and the administrators. Priests were hindered in their work and silence was imposed on them with regard to the local population. “The only way to consolidate our conquest,” he said, “is to show this Arab race, for whom religion is man’s whole being, that it is not dealing with conquerors devoid of prayer and worship.” Saint Charles de Foucauld would express a similar judgment. Thanks to his qualities as a leader and as a Christian, Sonis was respected by all, including the Arabs, whose language he learned. After a retreat at the Trappist monastery of Staouëli, he established nocturnal adoration in Algiers. In May 1859, Sonis was called to participate in the Italian campaign undertaken by Napoleon III to support King Victor-Emmanuel II against Austria. Although he did not approve of the expedition, he participated because he felt it was his duty, and distinguished himself at Solferino by his courage and military valour. After the battle, he visited the wounded. He received the Legion of Honor for his feats of arms, but deplored the many casualties of this battle, and the fact that he had indirectly favored the advancement of the Revolution: indeed, the King of Italy was soon to attack the Papal States.

“Make my father love you more!”

Sonis was then appointed Commander and Chief of Squadrons in the 2nd Spahis. In December 1859, he was able to return to his family for a four-month leave, during which he joined the Third Order of the Carmel. He then left for Algeria with his wife and six children. He followed the events of the Italian War and wrote to his friends that, had he not his family to provide for, he would have joined the Pontifical Zouaves, that had formed to defend the Sovereign Pontiff. He wrote to his son Gaston, who was in boarding school with his younger brother Henri: “I want your prayer for me to be the following: ‘My God, make my father love you more and more each day’… My beloved children, it is for me a great sacrifice to live so far away from you. But this suffering, like all the others, I place at the foot of the Cross of our Divine Master.” In 1861, he was posted to the oasis of Laghouat, at the edge of the desert. He dedicated his first visit to the Blessed Sacrament, the second to the serving priest and the third to the religious communities. Having learned of a massacre of civilians in Djelfa, he set off immediately and surprised the murderers in the early morning. He convened a council of war and had the culprits punished. This fact, which was amplified by those hostile to the army, damaged his career. He was removed and appointed Commander in Saïda. He obeyed without question, taking with him his wife who was expecting their seventh child. His spiritual life remained intense: “I have recently resumed the Exercises of Saint Ignatius, and I am still at the stage of fundamental meditation. That is the truly the foundation, and with God’s help, on it will I build the rest of my life.” On June 15, 1864, the Sonis lost their little Marthe-Carmel, aged three.

In 1865, Napoleon III landed in Algiers and asked for a worthy officer to be his guide. When approached, Sonis declined the offer. In June of the same year, he was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel of the 1st Spahis in Laghouat, from where he had been dismissed four years earlier. The south of Algeria was ablaze, assassinations were counted by the hundreds. Not without difficulty, he managed to pacify the region for several years. In January 1867, his son Henri, aged fourteen, asked him for permission to join the Pontifical Zouaves. He replied: “You had not yet told me that you loved God with passion, that all things noble and beautiful could make your young soul thrill and raise it to great heights. Yes, I permit you to leave for Rome… My child, you are going to serve the greatest cause that exists on earth, since it is that of the Vicar of Jesus Christ.”

Where lies happiness?

The Algerian population was suffering from hunger and cholera. Sonis devoted himself as best he could. In a letter to the Countess de Sèze, he wrote: “Our sufferings are so light compared to those that these unfortunate Muslims endure with such courage. Please do pray that Our Lord may illuminate their darkness, for there is no doubt that this people, once it becomes Christian, will be destined to serve God in a very different way than these bastard nations of Europe who have no more faith than they have courage.” He later wrote, “I do not know where happiness lies, if it is not in the love of God.” “The greatest poverty of peoples is not to know Jesus Christ,” St. Teresa of Calcutta later echoed.

In 1869, the Sonis family welcomed their twelfth and last child, Philomène, and Gaston sent his wife to France to rest and to oversee the studies of their children. “It is my dear children’s souls that are the daily bread of my thoughts… It is for them that I pray, that I work, that I meditate.” Marshal de Mac-Mahon, then governor of Algeria, happily announced to him that France would probably go to war with Prussia. While all the other officers applauded, Sonis declared that France was neither morally nor materially ready. Having observed the shortcomings of the army, he loyally reported them, despite the official propaganda. War broke out on July 28, 1870. The French suffered a series of defeats, and the Emperor was taken prisoner at Sedan. After many orders and counter-orders, Sonis, now a Brigadier General, was informed that he was to command the 17th Corps. He was soon joined by an elite troop of former Pontifical Zouaves, commanded by Colonel de Charette. Mr. Dupont, the “holy man” of Tours, sent them a banner bearing this motto: “Sacred Heart of Jesus, save France!”

On November 23, a Prussian army commanded by the Grand Duke of Mecklenburg launched an attack in the vicinity of Orleans. On December 2, the first Friday of the month, Sonis received Holy Communion at the chaplain’s Mass at three o’clock in the morning, with a large group of Pontifical Zouaves. Summoned urgently to help by General Chanzy, Commander of the 16th Corps, whose mobile troops were being disbanded, Sonis agreed to take command in his place. The Prussians had retreated to Loigny, and Sonis understood that he must recapture that village, an essential position. He ordered one of his Generals, whose division was not far away, to join him, but the General never came. Moreover, the soldiers at the center of his own formation had also fled. At this point he unfurled his banner and launched an assault to drive the Prussians out of Loigny. “Three hundred Zouaves had joined the attack by my side,” he said. “My only intent was for them to produce a great moral effect capable of drawing the demoralized troops back to their duty. I myself was wounded by a shot to the thigh fired at point blank range. I no longer had the strength to hold my horse. I shouted to my orderly: “My friend, take me in your arms; it is over for today!” He laid me down on the ground… There I was, alone, motionless, lying on the earth and snow. Around me lay noble victims who had not bargained for their lives, but had given them freely for the great cause of the fatherland and of honor.” Sonis later noted, “If everyone had done his duty, we would have taken possession of Loigny.”

General de Sonis did his duty to the full. The rapporteur of the commission of inquiry, which met in August 1871, testified that Sonis, by stopping the enemy’s progress, had saved the 16th Corps (Chanzy’s) from imminent defeat, as well as the artillery of his own 17th Corps: “The charge of Loigny,” the rapporteur added, “will have its rightful place in our military celebrations.” On December 4, Sonis was amputated up to the upper third of his thigh; his other foot was frozen and had to be curetted to prevent gangrene. He was unable to sleep for forty-five days, suffering to the point of madness… After nineteen days of searching, Mme de Sonis at last located her husband. She was a comfort to all the wounded of Loigny. On March 22, 1871, the General returned to Castres after the armistice was signed. In October of that same year, Thiers, the provisional head of state, appointed him to head the 16th Military Division of Rennes. In spite of his infirmity and the suffering it caused him, Sonis remounted his horse and displayed a high level of professionalism in his work that won him the admiration of the other officers.

Like an obscure grain of sand

On December 2, 1871, the General was in Paris, and he asked Father du Lac to lock him up in his chapel to pray, explaining: “On the battlefield of Loigny, I made a vow to the Sacred Heart to spend this anniversary night in adoration.” His inner life was a faithful echo of a prayer written by his own hand, which would be found on him at his death: “My God! Here I am before Thee, poor, small, devoid of everything. I am nothing, I have nothing, I can do nothing… Thou art my all, Thou art my riches! My God! I thank Thee for having wanted me to be nothing before Thee… I thank Thee for the disappointments, the injustices, the humiliations. I recognize that I needed them… O my God! blessed art Thou when Thou testeth me… Annihilate me ever more. May I be part of the edifice, not like the stone shaped and polished by the hand of the workman, but like an obscure grain of sand, robbed from the dust of the path… I have no regret but that I did not love Thee enough. I desire nothing, but that Thy will be done.” He looked after his children and taught them. “What a joy,” he wrote, “to fashion these young souls for Heaven, and to prepare these young Christian hearts for the struggles of this world! I would rather see them die in misery than to know them ungodly or even indifferent.” In 1872, his eldest daughter Marie entered the Convent of the Sacred Heart. The three eldest sons of the General entered the military career and got married. Sonis took care of their wives as if they were his own daughters. In 1873, following a fall from a horse which broke his good leg, he was immobilized for forty days, and would suffer from the injury for a long time.

An old friend

In March 1880, he was posted to Châteauroux, and placed at the head of the 17th Division, under the orders of General de Galliffet. General de Galliffet surrounded him with thoughtful attentions and marks of veneration. He had him named Grand Officer of the Legion of Honor. Jules Ferry, a Freemason politician, who had just been promoted to the position of Director of Public Instruction, prepared a bill that excluded members of unauthorized congregations from teaching. The following November, the expulsion of the religious was implemented with the help of the army. General de Sonis did not want to take part in this operation and asked the Minister of War to be relieved of his command: “By entering the army, I sacrificed my life,” he wrote, “but I had no intention of sacrificing my honor.” The minister placed him on leave of absence, and Sonis left the Military Hotel for very poor lodgings in Châteauroux: “I must sacrifice my well-being to my honor as a Christian,” he wrote. “Poverty is an old friend.” However, he continued to receive his friends with exquisite politeness. On the subject of Providence, he noted: “Whilst God was giving me a large family, I never doubted that He would come to my aid in a quite supernatural way.”

In May 1881, General de Galliffet forced the hand of the Minister of War, who appointed Sonis as permanent Inspector General of the Cavalry. He accepted this position, which allowed him to remain independent from politics, and moved back to Limoges. The nocturnal adoration that he founded there is still very much alive. “I was happy to take up my place in the guard of honor of Our Lord. I take comfort in the Gospel’s account that, lacking the great and the rich, the poor, the lame and the crippled of my sort are invited to the wedding feast!” In May 1882, no longer able to ride and exhausted, the General applied for his retirement. He left Limoges for Paris on February 1, 1883. The Gospel and the “Life of Jesus Christ” by Ludolph of Saxony were the main objects of his study. On August 14, 1887, Mme de Sonis, finding him very weak, called a doctor and a priest. He confessed and received Holy Communion in his room. The next day, on the Feast of the Assumption, he received the last sacraments while fully lucid, and then entered into a protracted agony before gently surrendering his soul to God. “Mary is placed at the threshold of eternity to inspire confidence in those who must cross it,” he had told the dying at Loigny. At his request, a simple stone adorns his tomb, with the inscription: “Miles Christi” (soldier of Christ). He lies in the crypt of the church of Loigny-la-Bataille next to the tomb of General de Charette and the ossuary containing the bones of the 1,200 soldiers who fell at Loigny. The body of Gaston de Sonis was exhumed in 1929 and found intact. His beatification process is underway.

“We firmly believe that God is master of the world and of its history. But the ways of his providence are often unknown to us… We know that in everything God works for good for those who love him (Rom 8:28). The constant witness of the saints confirms this truth: St. Thomas More, shortly before his martyrdom, consoled his daughter: “Nothing can come but that that God wills. And I make me very sure that whatsoever that be, seem it never so bad in sight, it shall indeed be the best.” (CCC, nos. 314, 313.)

Following the example of General de Sonis, let us, as cooperators of the divine will supported by grace, enter deliberately into the divine plan, by our actions, our prayers, and also our sufferings.