November 2, 2022

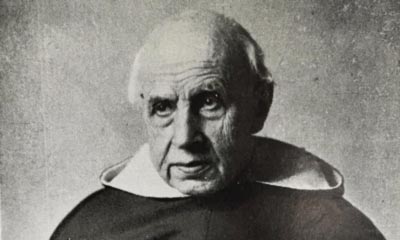

Ernest Psichari

Dear Friends,

At the turn of the 20th century, Catholics in France underwent the onslaught of an anticlerical Republic that established the separation of Church and State in 1905. Simultaneously, a wave of conversions was taking place among young intellectuals; it would later be described by Raïssa Maritain in a beautiful book entitled Les grandes amitiés (translated into English under the title We have been friends together). One of these admirable conversions was that of Renan’s grandson, Ernest Psichari, proving that the Holy Spirit lets his light shine even in the midst of darkness.

Ernest Psichari was born on September 27, 1883 in Paris, the eldest of four children. Jean Psichari, his father, was of Greek descent; he taught Greek philology at the École pratique des Hautes Études. His mother, Noémie, was the daughter of Ernest Renan, a French philosopher and former seminarian who had become an anti-clericalist. Renan was the author of a Life of Jesus marked by positivism and skepticism. Born into an upper-class intellectual family, Ernest Psichari was baptized, at his mother’s request, according to the Orthodox rite; she herself had been brought up a Protestant, and in this way sought to pay tribute to her husband’s parents. Ernest’s religious initiation ended there, and the child grew up in a family devoted entirely to the veneration of Renan, who had left his family a large inheritance that allowed them to live in material comfort.

Ernest Psichari was born on September 27, 1883 in Paris, the eldest of four children. Jean Psichari, his father, was of Greek descent; he taught Greek philology at the École pratique des Hautes Études. His mother, Noémie, was the daughter of Ernest Renan, a French philosopher and former seminarian who had become an anti-clericalist. Renan was the author of a Life of Jesus marked by positivism and skepticism. Born into an upper-class intellectual family, Ernest Psichari was baptized, at his mother’s request, according to the Orthodox rite; she herself had been brought up a Protestant, and in this way sought to pay tribute to her husband’s parents. Ernest’s religious initiation ended there, and the child grew up in a family devoted entirely to the veneration of Renan, who had left his family a large inheritance that allowed them to live in material comfort.

Wearing that old coat for a while

Mr. and Mrs. Psichari had frequent quarrels; Ernest, his brother Michel and his sister Henriette mostly lived with their mother and grandmother. They were the great-nephews and nieces of the painter Ary Scheffer and resided in Paris. Ernest was a very lively boy, with a marked taste for controversy. He was introduced to Renan’s ideas by his mother, while his father provided him with a vast humanistic culture. Jean Psichari, with his choleric temperament, did not take kindly to his son’s somewhat casual intellectual approach, but the two of them liked each other. The younger man revealed himself to be generous by instinct. One day his mother bought him a new coat. Meeting a less than affluent classmate, he pleaded with her: “Let me wear the old one for a while. He has no coat…” His mother ended up by giving in.

Jean Psichari often hosted notorious figures from the anti-clerical and anti-militarist political scene, such as Émile Zola, Jean Jaurès and Georges Clemenceau… Ernest was introduced to socialism by the family cook’s husband, an active socialist. Understandably, he developed a sense of guilt over enjoying all the material advantages of his well-to-do bourgeois social background. When he was fifteen, he met Jacques Maritain at the lycée Henri IV. Their families became friends. He also met Charles Péguy. Having obtained his baccalaureate, he prepared a degree in philosophy at the Sorbonne. Disappointed by the prevailing skepticism and relativism of the faculty, he decided to attend Henri Bergson’s lectures at the Collège de France. He then began to publish symbolist poetry, following a literary movement inspired by Baudelaire and Mallarmé, in various magazines. His was a pleasant existence, living in a world both elegant and liberal where he was fascinated by ideas, enjoyed debating, and studied literature.

At eighteen, Ernest fell in love with Jacques Maritain’s sister Jeanne, seven years his senior. That young woman did not take the teenager’s love for her in earnest, and soon married someone else. Ernest fell apart, plunging into a state of profound depression, with nothing to hold on to. He tried to drown his despair in debauchery, and on two occasions attempted to take his own life; fortunately, two friends intervened in time to save him. Ernest recovered from this breakdown very slowly and spent many months in the country, far from the sophisticated life he had known until then. His reflections led him to desire to establish within himself a deep-held sense of order, and to adhere to a school of discipline which he thought he would find in the army. In November 1903, he therefore anticipated the draft for military service and was posted to the 51st Infantry Regiment in Beauvais. After a period of adjustment, he regained a certain joie de vivre, a story he would tell in 1913 in L’Appel des armes (“The Call to Arms”): “When the author of this story first took up arms to serve France, it felt as if he were beginning a new life. He truly had the feeling that he was leaving the ugliness of the world and that he was taking his first step on a road that would lead him to more noble heights.” In 1904, after his military service, he joined the army; this choice outraged his friends, most of whom were anti-militarists who saw the army as a stronghold of reaction against modern ideas. In his autobiographical novel Le Voyage du centurion (“The Centurion’s Journey”), Ernest explained: “The young lad joined the army, suspending his studies, attracted and soon convinced by the beautiful ideas of order, obedience and sacrifice that are so vital to society.”

“She is crying over you!”

Little by little, his parents themselves came to understand that the military life was allowing their son to recover and mature. Moreover, it renewed his taste for writing. Ernest was appointed to the rank of corporal, then to that of sergeant in 1906. But soon, dissatisfied with garrison and barrack life in France, he obtained a transfer to the colonial troops as a non-commissioned artillery officer. Thanks to his parents’ connections, he joined the Congo mission of Major Lenfant, a friend of his family: its purpose was to explore new routes into Central Africa by land and water. During this stay in the Congo (from February 1907 to January 1908), Ernest was still an unbeliever. Jacques Maritain wrote to him: “I hope you will return from your solitudes believing in God!” In July 1907, playing on the same idea, Jacques wrote to him from La Salette: “We prayed for you from the top of the holy mountain. It seems to me that this so beautiful Virgin is crying over you, and that she wants you. Will you not listen to her?” Maritain’s renewed onslaught astonished Ernest as much as the previous one, and only prompted him to assert to himself his irreligious state. He met the bishop of Brazzaville, Mgr Augouard, a prelate and a missionary of outstanding caliber, as well as several Africans who won his admiration. The untamed wilds of the African continent made a deep impression on him. He described how one day a native, gesturing with his arm towards the horizon, said to him: “God is great!”

On his return to France in January 1908, Ernest was awarded the military medal. In his application for Psichari’s promotion, Lenfant pointed out: “He was in sole charge of launching the Pendé mission (500 men and as many oxen), and he led it with great initiative, energy, dedication, intelligence and care.” Now rejecting the anti-militarism of his youth, Ernest praised the army and the nation. He resumed contact with Maritain, who did not hesitate to incite him to convert, urging him to “receive what is best in time and in eternity: the peace of God, which the world cannot give”. But Psichari was not yet ready: “All I can say to you, for the moment, is that I am attracted to this beautiful spiritual house into which you want to draw me… I am attracted to your house, but I am not entering it.” Charles Péguy, who also exerted a great influence on him, wrote to Henri Massis: “What a pure soul! I, who have never had a brother, love him like a brother and thanks to him, I know what it is to have a brother.” During the eighteen months he spent in France, Ernest became fully aware of his military vocation under the influence of Péguy, to whom he would later dedicate his book L’Appel des armes.

We are beautiful!

After an eleven-month training course at the artillery school in Versailles, Psichari became an officer; he set off for Mauritania in September 1909. France’s presence in this part of the Western Sahara was being challenged by several tribes. Ernest spent three fruitful years there. His life as a méhariste squad leader was one of hard work and austerity, which at last made him break with his habit of laziness; he proved that he could endure hunger, thirst, sandstorms, the scorching heat of the sun and the dreaded ordeal of silence and solitude. While crossing the desert, he experienced the sense of his own nothingness in the midst of this world of still and forceful beauty. “You don’t know what it’s like to live for three years in a country where everyone prays”, he later said (Mauritania is populated by Muslims). He experienced a strong sense of God’s presence and, for the first time in his life, worshipped his Creator. “Question the beauty of the earth, question the beauty of the sea… question the beauty of the sky… question all these realities. All respond: ‘See, we are beautiful.’ Their beauty is a revelation. These beauties are subject to change. Who made them if not the Beautiful One (God), who is not subject to change?” (cf. St Augustine, CCC, no. 32).

Towards the end of January of 1910, Jacques Maritain encouraged Ernest to recite a prayer every day and sent him the text of the Hail Mary. Ernest effectively began to pray the Virgin Mary among the sands and the meharists. But his correspondence shows that he still had a long way to go. One day, while on an expedition in the company of Muslims, one of them who was always eager to talk to him asked him about the religion of the Christians, which he held in deep contempt. Stung to the core, Psichari started defending Jesus! Even though he was Renan’s grandson, he was proud to be French and had to recognize that it was the Catholic religion that had made France great. Understanding that he himself must still wait, and accept to undergo a time of preparation and purification, he became humbler in his supplication: “O my God, since You have brought me this far to give me a glimpse of Your face, abandon me no longer… In the same way that You showed Thomas Your bloody wounds, send me, my God, the sign of Your Presence…”

In an attempt to impress a group of Moroccans, he showed them some of France’s technical achievements. One of the chiefs replied: “Yes, you people of France have the kingdom of the earth, but we, the Moors have the kingdom of heaven.” This answer made him stop and think; he wrote to Bishop Jalabert, of Dakar: “In the six years since I got to know the Muslims of Africa, I have become aware of the madness of certain moderns who want to separate the French race from the religion that made it what it is, and from which all its greatness comes.” He had not been mistaken in seeking salvation in discipline, Jacques Maritain later pointed out. What sustained Ernest during all this time, and provided him with a purpose for living, was not only the power of oblivion and diversion provided by the harsh rule and the exhausting fatigues of army life, but also the understanding he had from the very outset of the formative and spiritual value of discipline freely accepted for a noble end. He sensed that his soul would be rectified, that his free will would be reinforced. “We are those who burn with the desire to submit, in order to be free”, Ernest later wrote in Les Voix qui crient dans le désert (“Voices crying in the desert”). “The more one does good, the freer one becomes”, the Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches. “There is no true freedom except in the service of what is good and just. The choice to disobey and do evil is an abuse of freedom and leads to the slavery of sin” (no. 1733). For Ernest, the ultimate fruit of his obedience as a soldier was freedom and spiritual liberation. The army showed itself to be a school of resolve and a training ground for the free will, and also a school of dedication and a field wide open to the generosity proper to the big-hearted. Is not the entire army essentially devoted to the good of another than itself, to the good of the homeland? “We understand the nature of a soldier’s submission”, he noted. “But we also know that it is only a figure of a much higher submission.” “Human freedom attains its perfection when directed toward God, our beatitude… As Christian experience attests especially in prayer, the more docile we are to the promptings of grace, the more we grow in inner freedom and confidence during trials, such as those we face in the pressures and constraints of the outer world. By the working of grace, the Holy Spirit educates us in spiritual freedom in order to make us free collaborators in his work in the Church and in the world…” (CCC, nos. 1731 and 1742).

Desire for confession

On December 8, Psichari embarked from Dakar; three weeks later, he was in Paris. Jacques Maritain and Ernest started meeting every day and discussing Catholic doctrine together. Ernest soon learned that his baptism in the Greek rite, received from an Orthodox priest on November 25, 1883, two months after his birth, was valid, and that it had forever imprinted “the Redemptive Sign” on his infant soul. On January 31, he met Father Clérissac, and noted in his journal: “Picked up Jacques at Stanislas. We travelled together to Versailles and at his home I discovered Father Clérissac, of the Order of St Dominic. The man has a magnificent head, eyes like fire, a countenance of suffering and faith. You can sense that he is an ardent man, with a solid mind and a big heart, full of an inner, radiant fire. We went for a walk in the park, and I told him of my great desire for confession and of my sense of my own unworthiness. He helped and encouraged me with an inspired goodness that went straight to my heart.”

“Their second meeting took place on Monday, February 3”, Raïssa, Jacques Maritain’s wife later recounted. “Ernest and Father Clérissac had lunch with us. The moment was one of perfect harmony and poignant emotion, because a serious decision was at hand, one that would engage an entire life. After lunch, Father took Ernest to the park. Their absence lasted two hours, during which we did not stop praying. They returned at last… The next day, Ernest Psichari knelt before the statue of Our Lady of La Salette and made his profession of faith, followed by a general confession. He was confirmed on Saturday, February 8 in Versailles by Mgr Gibier. ‘It seems as if I have another soul’, he told the bishop after the ceremony.” He took the name of Paul at his Confirmation, in reparation for the affronts with which Ernest Renan, his grandfather, had covered the Apostle in his book Saint Paul. The next day, on February 9, Ernest Psichari made his First Holy Communion. He experienced that entire day as “magnificent, sun-filled, and full of pure radiance”. It pained him to announce the news to his mother, the daughter of Ernest Renan and the Protestant Cornélie Scheffer, dreading her reaction. “Mama, I have to tell you: I have become a Catholic, and I have made my First Communion. Perhaps this will upset you.—On the contrary: you were right, since you thought you ought to do so.” She went to her jewelry box to fetch the little gold cross that had been given to her first-born child at his Baptism. Ernest fell to his knees to accept it, kissing his mother’s hands. He would never cease to surround her with the most delicate and tender affections, especially since her husband, Jean Psichari, had just deserted her.

Deep fervor

On June 2, Psichari returned to the garrison of the 2nd Colonial Artillery Regiment in Cherbourg. Encouraged by Father Clérissac, he wrote Le Voyage du centurion, an autobiographical novel which was published posthumously in 1916. Under the pen name of Maxence, Ernest wrote an account of his journey, which was at the same time the diary of his spiritual journey. In the months that followed, Ernest ran a giant race, fulfilling the words of Our Lord: Be perfect as your heavenly Father is perfect (Mt 5:48). In October 1913, he made a retreat in a Dominican convent. He received the scapular of the Third Order of St Dominic. Every morning he took communion at seven o’clock Mass; witnesses of these moments would call them unforgettable. “He prayed like a saint”, the parish priest recalled: “Like a saint, with unimaginable fervor.” Ernest visited the Blessed Sacrament every day, even during maneuvers, whenever his service gave him the opportunity. He loved meticulous practices such as novenas, the rosary, the saint of the day, and the Office of hours recited at the appointed time.

On one of his maneuvers, he walked the fifteen miles (24 km) from Cherbourg to Valognes. It was a Sunday and he arrived around noon, for the conclusion of High Mass. He went to the church and asked the priest to give him Holy Communion. “But have you observed the fast?”, the priest asked, astonished (in those days the Eucharistic fast started at midnight).—Yes, Father, because I was hoping to receive Holy Communion when I arrived here.” This intimate love of the Eucharistic Jesus blossomed into a love of the poor and the humble: he gave away all he had and more, thanks to his mother who would often fill his always empty purse. Little by little, he turned to the religious life in the Order of Saint Dominic. Father Clérissac never ceased to tell him: “You must be a saint… God wants it!” Ernest was filled with the desire to make reparation for the offence his grandfather had committed against God, and he asserted in a broader sense: “Our mission is to redeem France with our blood.”

“That I may not hesitate!”

Ernest fought in the First World War as a lieutenant in the 2nd Colonial Artillery Regiment. His regiment left Cherbourg on August 6, 1914, heading for Belgium whose neutrality had been violated by Germany. There he joined the 4th Army, under the command of General de Langle de Cary; it was in charge of covering a 45 miles front (70 km) between Mézières and Montmédy. He was under no illusions: “We are not ready; but I put my trust in the Sacred Heart.” He confided to a priest friend: “Pray for me, that I may never hesitate in the face of duty!” On the day of his departure, he had lunch at the rectory of Notre-Dame du Vœu. The meal was very joyful. On leaving the parish priest, he pronounced these last words in a voice choked with emotion: “Please do pray for my poor mother!” On August 20, he wrote to his mother: “My command, however modest, gives me the greatest satisfaction.” The influence he exerted on his soldiers was amazing: in particular, he succeeded in getting his gunners to stop cursing and, in his battery, they even formed two “living rosaries”: thirty men undertook to recite a decade of the rosary every day.

On August 21, at 6 p.m., Psichari received orders to launch an offensive: he must advance to Neufchâteau, with the mission of attacking the enemy wherever encountered. His petty officer, Galgani, would later report: “We had just started out on the road, entirely without cover, when my lieutenant gestured with his arm, as if to tell me to move quickly because it was a dangerous spot… I heard him shout out to me: “Gal…” He got no further. He spun round and fell with his arms outstretched… Lieutenant Psichari had been shot in the temple…” The military medal he had won in Africa, which he loved so much, remained attached to his jacket… The men who buried Ernest, his comrades, also saw a thin gold chain around his neck, at the end of which hung a small cross, that of his Baptism… An elderly nun, come to offer her prayers for the dead and to help the soldiers in their mournful task, was kneeling beside him: “What is that on the left wrist of this young officer whose features are so pure, almost childlike still?” Lifting up his sleeve, she discovered a rosary with black beads, on which his now livid lips had counted so many prayers. Ernest had worn it wrapped around his arm in the horrors of battle. He fell at Rossignol, Belgium, on August 22, 1914, in one of the very first battles. He was buried in a mass grave; his body was identified on April 9, 1919 thanks to his scapular of the Third Order of St Dominic and the small gold cross of his Baptism.

On May 30, 1913, Ernest wrote in his diary: “In all truth, in all sincerity, I say this before God: my only desire on this earth is to have the Faith, Hope and Charity of the saints; my only desire is to die for the adored name of Our Lord, if he wills us to be his martyrs. My only desire and my only thoughts are of Paradise!” Let us ask the Holy Spirit for a similar disposition.