August 24, 2022

Venerable Satoko Kitahara

Dear Friends,

The first snows of winter had fallen on the slopes of Mount Fuji (Japan). From her chaise longue, Satoko never wearied of gazing at the perfect white cone of the volcano, looming up against the deep blue sky. Yet the young girl was eager for the period of rest forced on her by tuberculosis to end. Her desire was to return to Tokyo, and to the ragpickers of Ants Town… The nurse who looked after her had no idea that this upper-class girl’s thoughts were fondly turned towards the inhabitants of a shantytown in the capital.

Satoko Kitahara was born on August 22, 1929, in Tokyo, to an aristocratic family descended from a long line of Shinto priests; the Shinto religion, in which everything is sacred, purports to lead its followers into the harmony of multiple ancestral traditions. Satoko’s father, who was an eldest child, was disinherited for refusing to accept the traditional role of the first-born, that would have prevented him from attending university. He completed a very thorough education in Tokyo, the capital since 1866, and after his father’s death was reintegrated into his family. When his fourth child, Satoko, was born, he was himself in the process of obtaining a prestigious doctorate. From childhood, Satoko was a diligent student and she revealed herself to be a highly gifted pianist, indeed hoping to make a career in this field. Out of obedience to her father, however, she agreed to complete her studies as the war raged on. The young girl was just fifteen when she was called up to serve in an airplane factory where working conditions were very harsh. The first signs of pulmonary tuberculosis began to appear; she hid them as best she could. In Japanese society at the time, many people believed that illness reflected an internal disharmony. Thanks to her mother’s good care, Satoko’s health improved and, in 1946, she embarked on a course of studies in pharmacy.

Satoko Kitahara was born on August 22, 1929, in Tokyo, to an aristocratic family descended from a long line of Shinto priests; the Shinto religion, in which everything is sacred, purports to lead its followers into the harmony of multiple ancestral traditions. Satoko’s father, who was an eldest child, was disinherited for refusing to accept the traditional role of the first-born, that would have prevented him from attending university. He completed a very thorough education in Tokyo, the capital since 1866, and after his father’s death was reintegrated into his family. When his fourth child, Satoko, was born, he was himself in the process of obtaining a prestigious doctorate. From childhood, Satoko was a diligent student and she revealed herself to be a highly gifted pianist, indeed hoping to make a career in this field. Out of obedience to her father, however, she agreed to complete her studies as the war raged on. The young girl was just fifteen when she was called up to serve in an airplane factory where working conditions were very harsh. The first signs of pulmonary tuberculosis began to appear; she hid them as best she could. In Japanese society at the time, many people believed that illness reflected an internal disharmony. Thanks to her mother’s good care, Satoko’s health improved and, in 1946, she embarked on a course of studies in pharmacy.

Satoko learned about Japanese war crimes through the press. She had always held the Japanese nationalism linked to her ancestral religion in high esteem, but she was deeply shocked by her discovery and gradually distanced herself from her traditional beliefs. While in her third year of study, she travelled with another young woman to Yokohama, the port of Tokyo, 20 miles south of the capital. Out of curiosity, she and her friend entered a small Catholic church: they were both struck by the reverent atmosphere of the place. In a side chapel they noticed a statue of Our Lady of Lourdes. With her knowledge of art, Satoko was able to tell her companion that this was Mary, the mother of Jesus Christ. She later recalled: “I still remember the first time I went into a Catholic church and saw a statue of the Blessed Virgin… I was immediately gripped by a strangely appealing force. From childhood, such a strong yearning for purity had dwelt in me that I could not clearly describe this attraction in words.”

The transparency of her gaze

In March 1949, she passed her final exams with flying colors and received several employment offers, which she refused: she wanted to take time to reflect and find her inner harmony. At that time, Mrs. Kitahara, who wanted to give her daughter Choko the best possible education, enrolled her in a Catholic school run by Spanish Sisters of the Congregation of Our Lady of Mercy. Satoko accompanied them to the opening ceremony of the school year. The superior delivered a speech in fluent Japanese: “God, in His providence, has brought your daughter to this school…” The word “providence”, whose use she had noticed among Christians, was a source of profound reflection for Satoko. A few days later, she accompanied her sister to school and met one of the sisters with whom she spoke briefly. The transparency of the nun’s gaze provoked a reaction similar to what she had experienced in front of the Virgin of Yokohama. Feeling perturbed, she tried to find distraction in the movies and the theatre, attending to her personal appearance and clothing. But a few days later, she returned to the institute. The nun who received her suggested that she take a catechism course.

The sister wisely suggested studying catechism, rather than just reading the Bible. Indeed, “the organic presentation of the faith is an indispensable requirement. The Catechism of the Catholic Church, as well as the Compendium of this same Catechism, offer us exactly this full picture of Christian Revelation, to be accepted with faith and gratitude” (Benedict XVI, General Audience, December 30, 2009).

The desire to serve

Satoko attended the course with great assiduity, and went to Mass at the sisters’ convent at six a.m. every day. “After several months of catechesis”, she reported, “I was convinced that I had found the truth, and I asked to be baptized. The Church in Japan usually made catechumens wait for a whole year… but, because of my profound belief, I was baptized under the name of Elizabeth on Sunday, October 30, which in that year was the feast of Christ the King. Two days later I received the sacrament of Confirmation.” Her parents were troubled by the news that their daughter was entering a religion they did not know. But her father, remembering his painful confrontation with his own father, did not want to stand in the way of her freedom. He himself began to study Christianity and the life of St. Elizabeth of Hungary, his daughter’s patron saint, but that was all. Later, he would say that he understood why Satoko had chosen this saint whose fiery soul was like his daughter’s, and who was a Franciscan tertiary, at a time when Satoko was evolving towards the spirituality of St. Francis of Assisi. With the enthusiasm of the neophytes, Satoko was eager to dedicate herself entirely to charity towards her neighbor: “Since the day of my baptism, I have felt a strong desire to serve. I joined a group of women who met regularly at the convent of Our Lady of Mercy. We visited several orphanages and drew biblical scenes that were used to teach catechism to the children. In spite of this, I was still missing something more profound.” She began to ponder the possibility of a vocation to the religious life and discussed it with the Mother Superior, who invited her to spend some time in the Sisters’ novitiate in Japan. But suddenly a bout of tuberculosis forced her to observe a period of complete rest.

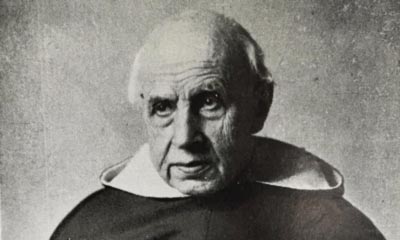

At about the same time, her father, who had been working much too hard to promote higher agricultural studies in Japan, suffered a serious incident of loss of consciousness. His eldest daughter, Kazuko, suggested to her parents that they move near her home at the other end of Tokyo, on the Sumida River. The move took place in September 1950, and Satoko followed her parents to their new home. There she met Brother Zeno Zebrowski, a Polish Franciscan missionary who had arrived in Nagasaki in 1931 with St. Maximilian Kolbe, there to establish the “Militia of the Immaculata” in Japan. Brother Zeno had soon become close to the most destitute, especially the inhabitants of a shantytown in the suburbs of Tokyo, where extreme poverty reigned. These poor souls had become ragpickers, a trade particularly despised by the Japanese, who worship cleanliness. The shantytown was set up on municipal land thanks to a ruined entrepreneur named Ozawa, who paid the ragpickers for the rags, paper and scrap metal they collected by weight. Shocked by the large number of homeless people in the post-war period, Ozawa grouped some of them together, taught them to work as ragpickers and to build shacks near the rubbish dump. In order to obtain a modicum of legal recognition, he consulted a law firm where he met Matsui. A writer-poet with a law degree, Matsui had spent most of the war in Taiwan. He returned to Japan after the war was lost and was attracted to Ozawa and the ragpickers’ community, which he referred to as “Ants Town”, and came to their aid. “Are Ozawa and Matsui Christians?”, asked Satoko. “No”, replied the Franciscan. “Matsui is, I believe, a bitter intellectual who has dabbled in Buddhism and Christianity without finding an answer to his sense of revolt.”

“Nobody likes ragpickers”

Brother Zeno gave the young woman a life of Father Kolbe and an issue of Knight of the Immaculata in Japanese. After reading it, Satoko decided to consecrate herself to the Immaculate Heart of Mary. She then committed herself to the poorest of the poor in the community of ragpickers. “Brother Zeno”, she wrote, “had discovered a Japan that I had never even known to exist. Thousands of people were enduring a life of total destitution, and some of them were less than a mile from my home. I was living in an affluent and well-cultured world, but this humble foreign Brother was giving his all, without any concern for himself, in the reality of this painful world.” Satoko soon stood out because of her dedication, her beneficent initiatives, her constant joy and her religious fervor. People said that she had become the smile and the angel of the ragpickers. She began by helping out at a Christmas party, and then took special care of the children, many of whom were orphans. One day, she asked one of them if he was going to school: “It’s been a long time since we went to school”, he replied. “Nobody likes ragpickers. And as soon as there is a theft, we are the ones who are accused.” So Satoko decided to be a teacher. When a child would reach a satisfactory level, she would enroll him or her in a local school, making sure that the homework was always properly done (under her own supervision). She also saw to the hygiene and cleanliness of these pupils, in order to avoid the scorn of their classmates and unwelcome remarks from headmasters. Her parents were not happy about her new activities; her father warned her about the risks to her health, but he let her make her own choices and witnessed the joy that her dedication brought her. One day, Satoko and Brother Zeno discovered homeless people who, having been chased away from everywhere, had settled in a cemetery. Many of them were addicted to alcohol, and resorted to brutality. “Faced with this new world, which was still strange to me, I felt like a little child”, she wrote.

Together with Matsui, Satoko wrote numerous newspaper articles to make their community known, to dispel prejudice and avoid expulsion: the aim was to make it clear that they were honest people who earned their living by a very particular kind of work, but without breaking any laws. One day Matsui lost his temper, pouring out his anger against Christians on Satoko: “If you were sincere followers of Christ, you would be poor and share the suffering life of the poor… You, in your refined two-story house, have no understanding at all of the misery of people living in misery 365 days a year!” Satoko was speechless. The man concluded: “There has been talk of establishing a church in Ants Town. If you and your kind still want to see this plan come to fruition, there is one condition: you will find it in the Second Letter to the Corinthians.”

Totally a ragpicker

On the day after Easter, following a discussion with a self-confident American missionary full of preconceived notions about the “ants”, Satoko developed a violent fever. Her tuberculosis, which had been under control for several years, had flared up with renewed intensity. She was forced to isolate and to observe complete rest. The children regularly came for news; she could hear their voices, but suffered from not being able to do anything for them. Feeling abandoned by all, she experienced a kind of spiritual night, feeling that she was no longer of any use at all, but only a burden for her family. Her rosary, however, remained her consolation. One morning, however, the grace she had received from Our Lady of Yokohama seemed to reawaken: she abandoned herself to the will of God. A few days later, her temperature returned to normal. “After a month spent in my room, I felt free… The light sound of the Sumida River punctuated my slow pace… All of a sudden, I saw a ragpicker rummaging through a bin. Before my meeting with Brother Zeno, I could only have looked at this scene with a sorrowful and anxious heart; now I admired his resigned countenance and felt as if I were his accomplice.” She had indeed meditated at length on the Second Letter of St. Paul to the Corinthians: Our Lord Jesus Christ, being rich he became poor, for your sakes; that through his poverty you might be rich (2 Cor 8:9). She therefore decided to become herself totally a ragpicker, to the point of fully sharing the lives of her friends.

One of the older boys told her that he and his father would soon be leaving Ants Town. She gave him a New Testament as a going-away present. “I want to learn to be a good ragpicker”, she told him.—“What do you mean? You, a ragpicker?”—“Yes!” A few days later, accompanied by a group of children, she started going through the rubbish bins. Her first excursions caused a scandal: Professor Kitahara’s daughter was assisting the ragpickers! Matsui was stunned, and Ozawa had tears in his eyes. While she was helping to sort out the loot, they both stopped by: “I see that your illness has opened your eyes!”—“It is true! From now on I am a ragpicker!” The children, who had followed the exchange, applauded joyfully. Now fully one of them, she was fully accepted by these poor people. But now she must break the news of her decision to her family: “With a resolute voice I told my parents: during this last month of solitude in my room, I finally realized clearly that, in order to help the ragpickers of the Town in all truth, I had to become one of them.” She later wrote: “The first time I found myself alone pulling a cart, I felt humiliated. The look of a passer-by made my embarrassment twice as bad. Ashamed of myself, I prayed to the Virgin Mary. I wanted to become a joyful servant of the Lord while collecting rubbish… When I lifted the lid of a rubbish bin and found some saleable goods, I got a taste of the pleasure that ragpickers can have at such times. Besides, I was so happy to have done the hardest bit.” She taught others how to sort the rags, wash the best ones and make decent clothes out of them.

“Lourdes of Ants”

On Pentecost day, Satoko went to the Town. She was surprised to see many ragpickers busy constructing a building: “You’ll have your church before long!”, said Matsui, who added, lifting a large cross: “And this is for the top of the roof!” To tell the truth, he was making a calculated move: the shantytown was threatened with demolition by the municipality in order to return the place to its original purpose as a municipal park; yet the municipality would never dare destroy a religious building, which was proof of an organized life, and therefore it would never raze Ants Town to the ground. The ground floor of the building would be a refectory where all the ragpickers could meet, and the first floor would serve as a classroom and a chapel. In the latter, a statue of Mary, procured by Brother Zeno, was called “Lourdes of Ants” by the children. Gradually, sewers, running water and a public bath were installed. Each time the idea came from Satoko, and Ozawa approved it. The fruits of the ragpickers’ labor made it possible to offer a holiday in the mountains to some. Satoko suggested using part of the earnings to set up a center for the elderly.

However, Satoko’s illness was still very active: at the beginning of December 1951, the doctor ordered her to take a complete rest. A great sadness overtook the patient, and Brother Zeno tried to encourage her: “Pray to Mary, she always helps us!” She then went to a sanatorium for six months. One day, when she learned that the Town was again under threat, she returned to Tokyo, determined to share the fate of her protégés. However, she still needed to take care and moved in with her parents, spending long hours answering mail and writing a diary. However, another girl, who had read about her work, had come to take her place with the children. When she met her, Satoko was deeply hurt, and found herself unable to say a word to her. She realized that life in the Town went on without her. A somewhat blunt intervention by Matsui, telling her that God’s will must be done, helped her to accept this new situation that she had not anticipated.

“It won’t be necessary”

Satoko’s illness grew worse. In isolation for fear of contagion, she entered a new night of the soul: her life had been a failure, she had not won anyone over to the Gospel… Yet her example had touched Ozawa. Moved by the fact that she had given her life so completely, he approached Matsui to tell him that he was thinking of becoming a Christian like her. Already shaken, Matsui divested himself of the cynicism in which he had sought refuge. He told his boss that he too wanted to be baptized: “Thanks to Satoko’s life of love, forgiveness, and mercy, my eyes have finally been opened.” Both enrolled in catechism classes. At Satoko’s bedside, they found her parents and her doctor. The doctor suggested a new change of scenery for his patient: why not move her, they wondered, to Ants Town which she loved so well? The ragpickers built her a plywood room in a corner of the warehouse. There she found back her smile, but not her strength. “Bedridden, I have nothing to do but give up my own will”, she thought. “It is difficult to be inactive while everyone is working. In any case, I have offered everything I owned to the Lord. How can I complain about my illness and suffering? Didn’t Jesus carry his cross? By accepting my life as it is, I can truly be the servant of the Lord.” She could still get up, walk a little and help Matsui with his paperwork. Her joy was intense when a grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes was erected near her room, and when several baptisms took place in the Town, including those of the two leaders.

In 1957, Satoko learned of a new plan to destroy the Town. Matsui went to the prefecture with a petition drafted with the help of Satoko, who had become famous for her works. She wanted to obtain another piece of land for Ants Town from the municipality. There was such a plot in the part of Tokyo that had been conquered from the sea. They would need 25 million yen to be able to buy it. Satoko put up a big banner in her room with the words “25 million”, and prayed without respite. At Christmas, her parents came to the Town to attend part of the celebrations. An inspection by a city official was positive. When, in January, a city employee came to announce that the price had gone down, Matsui did not hesitate to give Satoko the credit: “That’s it, we’ve succeeded and it’s thanks to your prayers. Now all you have to do is ask for your healing so you can come with us to organize the new Ants Town on our new land.” Her answer was plain: “No, it won’t be necessary. God has granted us everything we asked for. That is enough.” On January 22, 1958, Satoko received the last rites and died peacefully the next day at the age of twenty-nine. On January 23, 2015, Pope Francis recognized the heroic virtues of Satoko. In 1960, Ants Town moved to the land reclaimed from the sea in Tokyo Bay. In 1951, Abbé Pierre had founded the Emmaus communities in France. One of his collaborators, Father Robert Vallade, came to Tokyo and met Satoko who gave him sound advice on how to establish the movement in Japan. After Satoko’s death, Ants Town joined Emmaus International.

“The worst discrimination which the poor suffer is the lack of spiritual care. The great majority of the poor have a special openness to the faith; they need God and we must not fail to offer them his friendship, his blessing, his word, the celebration of the sacraments and a journey of growth and maturity in the faith,” wrote Pope Francis (Evangelii gaudium, November 24, 2013, no. 200). Won over to the Catholic faith by the example of a disciple of St. Francis, Satoko Kitahara herself gave up all the human advantages with which she had been endowed, to make the treasure of faith that brings Eternal Life, available to the poorest. Let us ask her to help us give concrete witness to our faith.