November 16, 2021

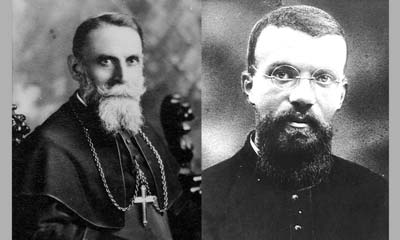

Venerable François Libermann

Dear Friends,

“The task of evangelizing all people constitutes the essential mission of the Church,” wrote Pope John-Paul II. The great missionary epic which took place on the African Continent during the last two centuries is a story that we should not forget. “The splendid growth and achievements of the Church in Africa are due largely to the heroic and selfless dedication of generations of missionaries. This fact is acknowledged by everyone. The hallowed soil of Africa is truly sown with the tombs of courageous heralds of the Gospel… Sacred Scripture admonishes us to ‘Remember your leaders, those who spoke to you the word of God; consider the outcome of their life; and imitate their faith’ (Heb 13:7)” (Exhortation Ecclesia in Africa, September 14th, 1995, nos. 55, 35, 37).

Father François Libermann is one of these evangelizers of Africa. Born Jacob Libermann in Saverne, Alsace, on April 11th, 1802, he was the fifth of the nine children of Lazare Libermann, the town’s rabbi. Jacob was circumcised shortly after his birth and educated in accordance with the most strict Jewish orthodoxy. He was delicate and frail, sensitive to the point of apprehensiveness, meek and gentle, shy, yet very intelligent; but he was also gifted with a practical mind and a persevering will. His father regarded him as his successor. Jacob had the great sorrow of losing his mother at the age of eleven. Until his twentieth year, he lived as a practicing Jew, leading a virtuous life, but the severity of some rabbis was shocking to him. In 1824, he moved to Metz to further his studies at a superior Israelite school where he did not receive the warm welcome he had anticipated, particularly from one of the teachers who had been his father’s student. There he deepened his knowledge of the Law and the Prophets; he also devoted himself especially to the study of French and Latin, two languages that would later be of great use to him.

Father François Libermann is one of these evangelizers of Africa. Born Jacob Libermann in Saverne, Alsace, on April 11th, 1802, he was the fifth of the nine children of Lazare Libermann, the town’s rabbi. Jacob was circumcised shortly after his birth and educated in accordance with the most strict Jewish orthodoxy. He was delicate and frail, sensitive to the point of apprehensiveness, meek and gentle, shy, yet very intelligent; but he was also gifted with a practical mind and a persevering will. His father regarded him as his successor. Jacob had the great sorrow of losing his mother at the age of eleven. Until his twentieth year, he lived as a practicing Jew, leading a virtuous life, but the severity of some rabbis was shocking to him. In 1824, he moved to Metz to further his studies at a superior Israelite school where he did not receive the warm welcome he had anticipated, particularly from one of the teachers who had been his father’s student. There he deepened his knowledge of the Law and the Prophets; he also devoted himself especially to the study of French and Latin, two languages that would later be of great use to him.

All his fears fell away

During his stay in Metz, he learned of the conversion of his older brother Samson, who was baptized in the Catholic Church together with his wife on March 15th, 1824. He attributed this conversion to natural motives and above all blamed his brother for the pain he had caused their father. Nevertheless, he continued to keep up a correspondence with him in which the proofs of the truth of the Catholic faith were often discussed. In November 1826, in Paris, he met Paul-Louis (David) Drach, a former Alsatian rabbi who had converted to Christianity. Jacob soon found himself alone there, in an intimate confrontation with the Christian Doctrine and the History of Religion before the Coming of Jesus Christ by the Abbé Lhomond (†1794). A first “conversion” came about, with the intellectual conviction that the Church holds the entirety of revealed truth. “This moment was extremely painful”, he would later write, for at heart, he still felt attached to the faith of his forebears. “It was then that, remembering the God of my fathers, I threw myself on my knees and begged him to enlighten me about the true religion. The Lord, who is close to those who call upon him from the bottom of their hearts, answered my prayer. Immediately I was enlightened, I saw the truth. Faith entered my mind and my heart.” This grace was so profound that he was allowed to receive Baptism on Christmas Eve of the same year, taking the name of François. On this occasion, the Lord gave him great confidence in His omnipotence; François also received the grace of a fervent love for the Blessed Virgin Mary. On Christmas Day, he made his First Communion: “All my fears and uncertainties suddenly fell away.” He was in his twenty-fifth year. François announced his conversion to his father in a letter, but received nothing but total incomprehension in return.

Filled with the desire to become a priest, François was admitted in 1827 to the Parisian seminary of Saint-Sulpice. “I am always happy, always content,” he wrote to his brother Samson: “My heart is always in perfect tranquility and nothing will have the power to disturb this peace.” And indeed, he would always radiate peace around him. As a superior, he later wrote to his missionaries: “Do not think that the ideal of a missionary is always to be on the move, always in effervescence. You will do a great deal, certainly, but with peace in your soul. If you are restless, troubled, or hurried, it is a sign that you have already forgotten Jesus.”

At this point, epilepsy began to manifest itself, and the disease was to afflict him for many years. In spite of his initial seizures, the year 1828 went relatively well, and the results of his studies were outstanding. However, at the end of the following year, he was struck down by a severe seizure which left no doubt as to the gravity of his condition. Thereafter, periods of remission would occur and, with time, he became capable of anticipating the attacks. He learnt how to look after himself and to practice calmness and equanimity with regard to what he called his “dear disease.” At the time, Church law did not allow epileptics to enter the priesthood. However, because of his good influence on the seminarians, François, who had declared that he could not return to the world, was allowed to remain in the Sulpician house in Issy-les-Moulineaux. “I am happy to have no other resource than God alone,” he said. For six years, he worked as an assistant to the bursar of the house, while continuing his studies. He was entrusted with various material tasks, as well as the work of receiving new seminarians and the spiritual care of the servants. His influence on the seminarians was considerable. His first letters of spiritual direction date from this period. In one of them he wrote: “The great principle of the spiritual life is to simplify things as much as possible. The more simple and uniform our conduct, the more perfect it is.”

Great imprudence

In 1837, he was urged to go to Rennes, to the Eudists (a congregation founded by St. John Eudes in 1643) to serve as assistant to the master of novices. He quickly gained the confidence and esteem of the young religious as well as of the superiors, but he felt neither useful nor in his right place. He remained there for two years. Two seminarians, Mr. Frédéric Le Vavasseur, a Creole from Reunion, and Mr. Eugène Tisserant, separately told him of their plans for the evangelization of the Blacks. Francis perceived that the Holy Spirit was calling him to collaborate in this work of evangelization. The young men asked him to adapt the Eudist rule to their missionary project. Little by little, though without seeking to do so, Francis took the lead in this undertaking, which took shape on July 28th, 1839. He wished to obtain the approval of the Holy See for this intuition, but all his advisors were of the opposite opinion. This was a source of deep dismay for him, which would only cease at the feet of Notre-Dame de Fourvière in Lyon. “I have left Rennes for good,” he wrote his brother Samson. “It is a great imprudence – not to say madness – according to those who judge things as men of this world. My future was assured, I was certain to have enough to live on and even to have a reasonably honourable existence. But woe to me if I seek to gain comfort on earth, and to live in honour and esteem. Remember this one thing: this earth passes away, the life we lead on it lasts only a moment… Have no fear; accept that I am the happiest man in the world, because now I have only God!”

He arrived in Rome in January 1840. There he met once again with Mr. Drach, who was now a librarian at the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith. They both obtained an audience with Pope Gregory XVI on February 17th. François prayed often and hard in the Roman basilicas, at the tombs of the Apostles, while meditating on his missionary design. The following month, he presented a brief to the Congregation. By the beginning of June, he learned that his plan for a work dedicated to the Blacks had found favour, provided that he be ordained to the priesthood. He was thirty-eight years old at the time, and since he had not had any epileptic seizures for a long time, his illness was considered cured. François stayed in Rome a few months more, putting the finishing touches to the rule he had prepared in Rennes, and writing a commentary on the Gospel of St. John.

“You shall turn to the poorest of the poor.”

During a pilgrimage to the holy house of Loreto, he accepted the idea of becoming a priest. Observing that his health was improving, he started to take steps in this direction with the bishopric of Strasbourg, his diocese of origin. On February 23rd, 1841, he entered the major seminary of Strasbourg. At the same time, M. de Brandt, a former seminarian of Saint-Sulpice, offered to rent a house for the new congregation in La Neuville, today a district of Amiens, and presented its candidates to his uncle, Bishop Mioland of Amiens. Following his diaconal ordination in Strasbourg on August 10th, 1841, François Libermann moved to Amiens where Bishop Mioland ordained him a priest on September 18th. On September 25th, he celebrated his first Mass of thanksgiving at the Parisian shrine of Notre-Dame-des-Victoires in the presence of most of his companions. It was, in a way, the founding Mass of the institute, which adopted the name of “Society of the Immaculate Heart of Mary.” On Monday, September 27th, the novitiate of La Neuville was established. A year later, the number of novices reached one dozen, including seven priests. In those early days of the foundation, there was great poverty and many had to sleep in the corridors, but joy and fervour filled them all.

In March 1842, Father Libermann bought the property of La Neuville and began the construction of two wings and a chapel. He himself participated with equal dedication in the gardening work and in the spiritual formation of his brothers: “I am a servant of Jesus. He wants me to love all men as he loves them; but He inspires me to have a greater and more tender love for black men.” The call received from the Lord drove him in this direction: “Thus you shall turn to the poorest of the poor, those whom no one thinks of.” He would later write for the intention of his sons: “It is not possible for you to sanctify yourselves without working with all your strength for the salvation of souls… It is hardly possible to sanctify these souls if you neglect yourselves.”

“It is often said nowadays that the present century thirsts for authenticity,” wrote Pope Paul VI, many years later: “Especially in regard to young people it is said that they have a horror of the artificial or false and that they are searching above all for truth and honesty. These ‘signs of the times’ should find us vigilant. Either tacitly or aloud – but always forcefully – we are being asked: Do you really believe what you are proclaiming? Do you live what you believe? Do you really preach what you live? The witness of life has become more than ever an essential condition for real effectiveness in preaching” (Evangelii Nuntiandi, December 8th, 1975, no. 76). Commenting on the verse: “Let us be concerned for each other, to stir a response in love and good works” (Heb 10:24), Pope Benedict XVI also echoed this advice: “This means that ‘the other’ is part of me, and that his or her life, his or her salvation, concern my own life and salvation. Here we touch upon a profound aspect of communion: our existence is related to that of others, for better or for worse. Both our sins and our acts of love have a social dimension” (Message for Lent in the year 2012).

As servants to their masters

After only four months of novitiate, Mr. Le Vavasseur left for his native land, Bourbon Island (today Reunion Island). Eugene Tisserant went to Martinique where he waited for an opportunity to enter Haiti. Thus, barely one year after the beginning of the new congregation, some of its members were already working in their fields of apostolate. On September 28th, 1842, the Holy See erected in Africa the immense Apostolic Vicariate of the Two Guineas and Sierra Leone; it stretched over eight thousand kilometres of coastline. It was entrusted to Bishop Edward Barron, former Vicar General of Philadelphia (North America). The prelate contacted Father Libermann who offered him the help of seven missionaries. Well aware of the harsh conditions of their mission, Father Libermann collected twenty tons of supplies and demanded that the missionaries undergo physical training. On September 13th, 1843, the seven priests, accompanied by three laymen, set out for Africa. “Strip yourselves of Europe,” the Father instructed them, “of its customs, of its spirit… Make yourselves Blacks with the Blacks to form them as they should be, not in the manner of Europe, but let them keep what is proper to them; adjust to them as servants should adjust to their masters; as they adjust to the customs, the way of being and the habits of their masters; and do all this to perfect them, to sanctify them, to make of them, little by little, over time, a people of God. This is what St. Paul calls making himself all things to all people, in order to win them all to Jesus Christ” (cf. 1 Cor 9:22).

To proclaim Jesus Christ does not contradict the respect due to peoples, but instead promotes it: “The Church,” wrote St. John Paul II, “holds that these multitudes have the right to know the riches of the mystery of Christ (cf. Eph 3:8) – riches in which we believe that the whole of humanity can find, in unsuspected fullness, everything that it is gropingly searching for concerning God, man and his destiny, life and death, and truth” (Ecclesia in Africa, no. 47).

On November 29th, 1843, the missionaries arrived in Liberia, where Bishop Barron had established his residence; however, he was not there himself to welcome them. Without waiting, the missionaries set about studying the local language with great enthusiasm. They adopted an austere way of life and a frugal diet. Their totally inexperienced zeal, in a country with an equatorial climate, produced dire consequences: in less than two weeks, seven fell ill, and by the end of December, death had claimed two of them. The Father wrote to his sons: “All the works that have been undertaken and carried out in the Church have encountered these same difficulties and often even greater ones, and yet these difficulties have not frightened apostolic men… It has always been in the order of Providence to manifest its maternal care in the midst of obstacles, and the happiest results were usually achieved after the greatest difficulties.”

“Walk at his pace!”

Bishop Barron decided to leave only Father Bessieux in Liberia with two companions, and took all the others to Grand Bassam (today in Ivory Coast); there they perished one after the other. In September 1844, the bishop, discouraged by this disaster, returned to Europe. “Above all, be a man of perseverance,” said Father Libermann to himself. “One does not undertake anything for Jesus without encountering difficulties and God likes to take his time. Walk at his pace.” Father Bessieux and Brother Grégoire, the only survivors of the expedition, then travelled to Gabon, and settled in Libreville.

At this point the Fathers of the Immaculate Heart of Mary came into contact with another French missionary congregation, the Spiritans, founded in 1703 by Claude Poullart des Places (1679-1709). This young aristocrat from Brittany was ordained a priest after giving up a career in the Parliament of Rennes. He brought together poor students who wanted to become priests and serve in poor parishes. Thus, on May 27th, 1703, on the feast of Pentecost, the Society and the Seminary of the Holy Spirit were born. From 1816 onwards, the seminary was also responsible for providing clergy for all the French colonies; the Spiritans mainly looked after the Europeans living in Africa. Now the Society founded by Father Libermann abounded in vocations but lacked a precise juridical status; that of Father Poullart des Places existed officially but had few active missionaries, and vocations were rare. Their similarity of purpose made it possible to consider the fusion of the two congregations. A scant number of formalities in Rome allowed the project to materialize on September 28th, 1848. In an address to the two superiors, the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith stated: “It is up to you to bring about the fusion of your two institutes so that, henceforth, the Congregation of the Immaculate Heart of Mary will cease to exist and its members and aspirants will be integrated into the Congregation of the Holy Spirit.” On the following November 3rd, Propaganda Fide approved the election of Father Libermann as superior of the Congregation of the Holy Spirit; he would reside in Paris.

Father Libermann had acquired a building near Amiens in 1846 to replace the house in La Neuville, which was too small. He also needed to find a place to receive his thirty students in their philosophy and theology years. He bought the abbey of Notre-Dame du Gard, a few miles north of Amiens. During his travels across France, the Father noticed that many poor people were just as abandoned there as in mission lands. He sought to include them in the call he had received earlier: “You will turn to the poorest of the poor, those whom no one thinks of,” steering the congregation towards social and religious action among the working class, in parallel with the missions themselves. In May 1851, he wrote his “Instructions to the missionaries,” a booklet of sixty-four pages, which constitutes his spiritual testament.

Zeal for souls

At the end of that same year, a great fatigue fell upon him: his health, which had always been precarious, deteriorated rapidly. Father Le Vavasseur, who had returned to his side after a fine missionary apostolate, wrote to the sick man’s brother, Dr. Libermann: “It is more or less the same illness as three years ago. He can hardly swallow anything.” On January 27th, 1852, he was given Extreme Unction. On the evening of January 30th, before the assembled community, the Founder haltingly pronounced these few words: “I am seeing you for the last time. I am happy to see you. Sacrifice yourselves for Jesus, for Jesus alone. God is everything, man is nothing. A spirit of sacrifice, zeal for the glory of God and for souls!” His death throes lasted until February 2nd. He died at the very moment that the Magnificat of the Vespers of the Purification of Mary was being sung in the nearby chapel. His last words were for God: “My God, my God…” In 1967, his remains were laid to rest in the chapel of the motherhouse of the Congregation of the Holy Spirit, in Paris, rue Lhomond (5th arrondissement), on Mount Sainte-Geneviève. The decree recognizing the heroicity of his virtues, published on June 19th, 1910, officially conferred on Father François Libermann the title of “Venerable.”

Father Libermann wanted his missionaries not only to make a genuine and profound effort at inculturation, but also to involve Africans in the evangelization of their own countries, by forming catechists, religious communities, and then indigenous priests. Pope John Paul II also exhorted young Africans in a special way: “I wish to appeal to the youth: Dear young people, the Synod asks you to take in hand the development of your countries, to love the culture of your people, and to work for its renewal with fidelity to your cultural heritage, through a sharpening of your scientific and technical expertise, and above all through the witness of your Christian faith” (ibid., no. 115).

Let us ask Venerable Francis Libermann for the grace of an ardent zeal for evangelization, on which the eternal salvation of countless souls depends. After his Resurrection, Jesus sent out his apostles: Go ye into the whole world, and preach the gospel to every creature. He that believeth and is baptized, shall be saved: but he that believeth not shall be condemned (Mk 16:15-16). “Evangelizing is in fact the grace and vocation proper to the Church, her deepest identity,” said St. John Paul II. “She exists in order to evangelize. Born of the evangelizing mission of Jesus and the Twelve… Like the Apostle to the Gentiles, the Church can say: I preach the Gospel… For necessity is laid upon me. Woe to me if I do not preach the Gospel! (1 Cor 9:16).” (ibid., no. 55).