September 8, 2021

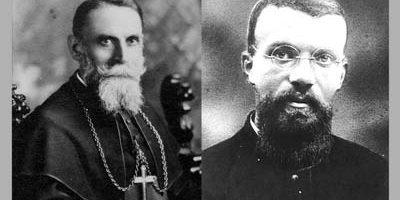

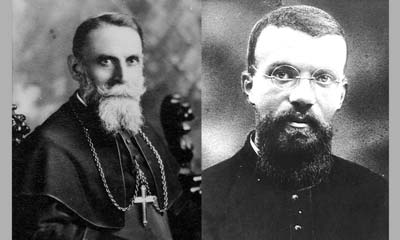

Saints Louis Versiglia et Calistus Caravario

Dear Friends,

China held a great attraction for the heart of St. John Bosco. Indeed, in a dream the saint saw two great chalices rise from that immense country to heaven, one filled with the sweat and the other with the blood of his spiritual sons, the Salesians. On February 25, 1930, two of these, Bishop Luigi Versiglia, the first Vicar Apostolic of Shiu Chow, and Don Callisto Caravario, a recently-ordained young priest, died defending faith and chastity, thus making Don Bosco’s dream a reality. “Following the example of Christ, they embodied to perfection the ideal of the shepherd of the Gospel: a shepherd who is both the Lamb (cf. Rev 7:17) and the one who gives his life for the flock (Jn 10:11), an expression of the Father’s mercy and tenderness; but also, a lamb which is in the midst of the throne (Rev 7:17) and a victorious lion (cf. Rev 5:5), a valiant fighter for the cause of truth and justice, a defender of the weak and the poor, a conqueror of evil, sin and death” (St. John Paul II, beatification homily, May 15, 1983).

Luigi Versiglia was born in Oliva Gessi, near Pavia, in Lombardy, on June 5, 1873. He was a lively child, gifted in arithmetic, and he had a passion for horses. At a very young age, he served Mass with great piety, so much so that people saw in him a future priest; but Luigi, whose dream was to become a veterinarian, did not listen. In September 1885, he was welcomed at the Valdocco Oratory in Turin by Don Bosco, who touched him so deeply that he ended up changing his mind. On June 24, 1887, the name-day of Don Giovanni Bosco, he was asked to pay him a compliment on behalf of the students. After the homage, as he kissed the old priest’s hand, the latter whispered in his ear: “Come and see me later, I have something to tell you.” The illness and death of the saint prevented this conversation, but the boy had been won over. In 1888, moved by the ceremony of the presentation of the crucifix to seven departing missionaries, Luigi decided to enter the Salesian Congregation, hoping to join the missions himself. In August, he began his novitiate in Foglizzo. On October 11, 1889, he took his vows. After completing a master’s degree in philosophy at the Gregorian University in Rome, he returned to Foglizzo where he taught logic to the novices. On December 21, 1895, he was ordained a priest with a dispensation from the Holy See because of his age, as he was not yet twenty-three.

Luigi Versiglia was born in Oliva Gessi, near Pavia, in Lombardy, on June 5, 1873. He was a lively child, gifted in arithmetic, and he had a passion for horses. At a very young age, he served Mass with great piety, so much so that people saw in him a future priest; but Luigi, whose dream was to become a veterinarian, did not listen. In September 1885, he was welcomed at the Valdocco Oratory in Turin by Don Bosco, who touched him so deeply that he ended up changing his mind. On June 24, 1887, the name-day of Don Giovanni Bosco, he was asked to pay him a compliment on behalf of the students. After the homage, as he kissed the old priest’s hand, the latter whispered in his ear: “Come and see me later, I have something to tell you.” The illness and death of the saint prevented this conversation, but the boy had been won over. In 1888, moved by the ceremony of the presentation of the crucifix to seven departing missionaries, Luigi decided to enter the Salesian Congregation, hoping to join the missions himself. In August, he began his novitiate in Foglizzo. On October 11, 1889, he took his vows. After completing a master’s degree in philosophy at the Gregorian University in Rome, he returned to Foglizzo where he taught logic to the novices. On December 21, 1895, he was ordained a priest with a dispensation from the Holy See because of his age, as he was not yet twenty-three.

In 1896, Don Versiglia was appointed director and master of novices at the Genzano house in Rome. He remained there for nine years. A novice wrote: “He is demanding of us, but he is much more demanding of himself. He does not spare us corrections, which he makes when and where appropriate with great charity and even-temperedness. Himself a tireless worker, he is like an iron hand in a velvet glove towards those who show a tendency to laziness. He is lenient towards those who are slow to learn and spares no effort to help them, or to give them his encouragement.” However, Don Versiglia still aspired to the missionary life, and he even prepared for it with physical exercises. In 1905, his lifelong dream came true at last: he was chosen to lead the first Salesian expedition to China. Arriving in Macao in 1906, the brothers began by opening a modest orphanage. In 1917, Bishop de Guébriant, of the Foreign Missions of Paris, who governed the province of Canton as Vicar Apostolic, transferred the region of Leng Nam Tou to their care. In 1920, it was erected as the apostolic vicariate of Shiu Chow. On that occasion Don Albera, Superior General of the Salesians, sent a chalice to Don Versiglia. With premonition, the latter told the brother who presented him with it: “You have brought me a chalice, and I accept it. Don Bosco saw that the missions in China would flourish when a chalice would be filled with the blood of his sons. The chalice has been sent to me: it is I who must fill it.”

“A missionary who is not united to God is a canal that detaches itself from its source,” he wrote. “A missionary who prays abundantly will also do much. Have great love for souls: this love will be the master of all industries to do them good.” Don Luigi was appointed Vicar Apostolic of Shiu Chow on May 4, 1920, and received the episcopal ordination on January 9, 1921. The following years were dominated by work, travel, and foundations: Bishop Versiglia performed wonders in a land hostile to Catholics, and displayed his abilities in organizing the vicariate. His constant concern was the care of his missionaries, Christian formation and the conversion of the infidels. As a superior, he strove to be more a father and brother than a man who gave orders, and the missionaries and Christians loved and obeyed him willingly. He founded elementary schools in almost all the missionary centres of the vicariate. When he arrived, there were eighteen such centres; in 1930, there were fifty-five. In the local capital, he opened schools for teachers and catechists, a professional school, a hospice for the elderly, a medical dispensary and a minor seminary. He ordained twenty-one priests in twelve years.

The mandate of Christ

Faced with contemporary objections to the need for missions, Pope St. John Paul II wrote: “As a result of the changes which have taken place in modern times and the spread of new theological ideas, some people wonder: Is missionary work among non-Christians still relevant? Has it not been replaced by inter-religious dialogue? Is not human development an adequate goal of the Church’s mission? Does not respect for conscience and for freedom exclude all efforts at conversion? Is it not possible to attain salvation in any religion? Why then should there be missionary activity?… We answer: The Church cannot elude Christ’s explicit mandate (Go ye into the whole world, and preach the gospel to every creature… [Mk 16:15]). The subject of proclamation is Christ who was crucified, died and is risen: through him is accomplished our full and authentic liberation from evil, sin and death; through him God bestows ‘new life’ that is divine and eternal. This is the ‘Good News’ which changes man and his history, and which all peoples have a right to hear” (Encyclical Redemptoris missio, 1990, nos. 4, 11, 44).

Bishop Versiglia’s missionary labours took place in a turbulent political context: one year after the proclamation of the Chinese Republic in Nanjing on October 10, 1911, the abdication of the emperor, a seven-year-old child, ensued. After the death of the first president of the Republic, Yuan Che-K’ai in 1916, a period of anarchy set in, which General Chiang Kai-shek ended with his 1927 victory over the “warlords” who were tyrannizing several regions. But Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists clashed with the Communists of Mao Zedong. In the midst of this chaos, the missionaries, described as “white devils,” were the object of violence, especially on the part of the Communist soldiers for whom the destruction of Christianity was a programmatic duty. In a letter dated January 1926, Bishop Versiglia wrote: “As you can see, we are in the midst of Bolshevism and we do not know where it will lead us… We know well that everything is in the hands of the Lord, and we are resolved to fulfill his holy Will, even at the cost of our lives.” He wrote to one of his collaborators, “If the Lord desires a victim for the good of the Mission, I am ready!”

All the way to China

In 1922, Bishop Versiglia had returned to Turin to participate in the General Chapter of the Salesian Congregation. Many religious had been touched by this missionary bishop: among them, young Callisto Caravario generously offered himself to join him: “Yes, Monsignore, you shall see. I will keep my word. I will follow you all the way to China.” Callisto Caravario was born in Cuorgnè, in the province of Turin, on June 8, 1903. His parents’ only riches were their profound faith. In 1908, the family moved to Turin. There Callisto was enrolled in the public school. Together with a few friends, he attended a retreat at the Sisters of the Cenacle in preparation of his First Holy Communion. The good-natured teenager showed himself to be obedient, obliging and temperate. He showed a tender affection for his mother; when he noticed sadness on her face, he would take her hands and tenderly say: “Courage, mother, I will pray for you!” Callisto attended St. Joseph’s Oratory run by the Salesians, and then, beginning in 1913, classes at their St. John the Evangelist College. At the Oratory, he played games, but he also helped keep the rooms clean and tidy. He revealed himself as a little apostle to his classmates, cultivating their good humour and piety. Serving Mass was a joy: for that he would rise early, at the risk of waiting for a long time at the door of the school, even in winter. Following the example of St. Dominic Savio, he gave the example of his angelic purity of conduct, nourished by frequent Communion.

Despite the opposition of some family members, Callisto made no mystery of his aspirations to the religious life. The superior of his school was in no doubt as to the boy’s vocation, and he took it upon himself to find benefactors to finance his education, since his parents could not afford it. In the fall of 1914, Callisto began to study Latin. Four years later, having barely turned fifteen, he asked to enter the Salesian Congregation. On November 21, 1918, he donned the cassock, and in September of the following year, he took his first vows. From 1921 on, he continued his training, first at St. John’s College, and later as an apprentice at Valdocco. But his great desire was always to go to the Missions of China. The flame of apostolic zeal was consuming him, and he was ready to sacrifice everything for the spread of the Kingdom of God among non-Christians. In October 1924, his desire was fulfilled: on the 7th, he sailed for Hong Kong. “The Lord has given me the strength to make the sacrifice of myself willingly, and better still, joyfully,” he wrote to his mother. “Continue to pray for me!” From Macau, on December 11, he confirmed: “As for me, I do not regret having left Italy: on the contrary, I am happy. It was a great sacrifice, I know; but the Lord will help me. I know that my departure has done good to many and will continue to do so.”

Don Caravario was assigned to the St. Joseph’s Orphanage in Shanghai, where he doggedly applied himself to the study of Chinese, French and English. Before long, he was able to make himself understood by the children taken in there. His first concern was to teach the catechism, in order to prepare the many children who asked to be baptized. He was attentive to indigenous vocations, choosing among the youngsters those who showed signs of a calling, and followed them more closely, educating them in piety, purity and joyfulness. He had the satisfaction of seeing two of them enter the Salesian Congregation. His charity was no less towards the physical needs of the students, most of whom were brought to the orphanage not only dirty and clothed in rags, but also in a miserable state of health. Thanks to his care, about a hundred children were soon healed in body and soul.

A discreet visitor

At the same time, Don Callisto continued to study theology. But the advance of the Communist troops in 1926 forced the Salesians to leave Shanghai, and he was sent to Timor (an island in the Indonesian archipelago, under Portuguese rule at the time), where he arrived in April 1927. The two years he spent there among the boys of the school of Dili revealed his qualities as an educator. “For me, Don Caravario was the ideal Salesian: humble, obedient, pious and energetic… Here, I thought, was the future superior of the Mission of Timor! In a few years, this island could be entirely Christian thanks to his piety and zeal. His visits to the Blessed Sacrament were frequent and prolonged. Every evening, after prayers, when everyone had withdrawn to rest and he thought that no inquisitive eyes were watching, he would go down to the chapel, slowly and on bare feet; kneeling on the little step of the altar, straight, motionless, head bowed, hands joined, he would spend a good half hour in adoration.”

In January 1929, Don Callisto announced to his mother his imminent ordination to the priesthood: “May the Lord make of me a priest according to his Heart!” He left Timor in March 1929. His regret to leave the island was softened, Don Rossetti later testified, by the great probability of martyrdom that China was offering him: “This supreme test of love for God and for souls was, one might say, a daily topic of conversation: it was a discussion that I gladly triggered, in my delight at seeing him flare up, and at hearing him respond to the reasoning of those who did not share his enthusiasm.” When bidding his farewells, Don Callisto stated that he was returning to China, “where martyrdom awaited him.” On June 18, he was ordained a priest at Shiu Chow by Bishop Versiglia. That same evening, he wrote these lines to his mother, the confidante of his apostle’s heart: “I am writing to you today, my good mother, with a heart full of joy. This morning I was ordained a priest… Thank the Lord with me for this truly extraordinary grace… The greatest desire of my heart has been fulfilled. Tomorrow I will go up to the altar for my First Mass… What shall I say to you, my good mother? That you should thank the Lord with me and ask Him to grant me fidelity to the solemn promises I have made to Him.” Then, under the action of the Holy Spirit, as if foreseeing what awaited him, he asked this question: “Will my priesthood be long or short? I know not. The important thing is that I do good and that, when I come into the presence of the Lord, I be able to tell Him that, with His help, I have made the graces He has given me bear fruit.”

Winning their friendship

At the beginning of July, Don Caravario arrived at Lin Chow, the first missionary territory entrusted to him by Bishop Versiglia. Accompanied by a Chinese catechist, he visited every one of the Christian families. Neither difficulties nor prejudice prevented him from adapting to local customs and habits. He showed himself pleased with everything, concealing his fatigue and discomfort, and was always ready to exercise his ministry. He soon won the friendship of the students of the school and impressed upon them the devotion to the Holy Eucharist. Several times during the day, Christian and pagan students would go to the chapel to visit the Blessed Sacrament. They all studied the catechism diligently. Don Callisto’s successor later testified: “I noticed how flourishing the mission was in which Don Caravario had worked for six months. Religious practice was fervent, the schools were well kept, the catechists were well prepared to teach doctrine. It was a fully efficient mission, rich in promise for the future.”

In February 1930, Don Caravario journeyed to Shiu Chow to visit Bishop Versiglia, whom he had been asked to accompany for the pastoral visit of his mission in Lin Chow. However, a guerrilla war was raging in the southern territories of China: pirates and communist revolutionaries made travel dangerous. Bishop Versiglia decided to set out anyway: “If we wait until the roads are safe,” he said, “we will never leave. No, woe betide if fear should get the better of us! Let happen what God wills.” Besides the bishop and the young priest, the group consisted of two boys who were returning home for the holidays, two sisters, and a young woman, Maria Thong, who intended to become a nun in an indigenous community founded by the bishop. These had all delayed their trip so as to be accompanied by the missionaries.

On February 24, they left by train for Ling Kong How. The next day, they continued by boat on the Pak-kong River. At noon, while they were reciting the Angelus, a savage cry suddenly erupted from the shore: a dozen men armed with guns were yelling: “Stop the boat! Disembark!—It is not necessary, we are from the Mission.—Disembark anyway!” The boatman approached the shore. In the boat, under the roof of the shelter, the young women prayed, trembling. “Under whose protection do you travel?—Under no-one’s,” replied the boatman, “no one has ever imposed this on the missionaries.—Your fine will be five hundred dollars.—But we don’t have such an amount of money!” Two men stormed the boat and spotted the women: “Let’s take the women!” But already the bishop and the priest were shielding them with their bodies. The pirates rushed at them and, swearing and cursing, hit them with the butts of their rifles. The bishop fell to the ground. Don Callisto resisted the attackers, before collapsing in turn, murmuring, “Jesus… Mary!” The young women still resisted. “Daughter,” Bishop Versiglia whispered to Maria Thong, “increase your faith!” The struggle continued, but the forces were now unequal. It was no longer a question of transit permits, nor of taxes to be paid: the real motives for so much violence were hatred against the missionaries and passion for the women. An inquiry would later reveal that this was a well-prepared ambush: the target was the young candidate to the religious life, who for several years had refused to marry a brigand chieftain.

They died happy

The missionaries were dragged into a nearby wood. Bishop Versiglia made a last attempt, offering money to rescue the young women from the clutches of the pirates. One of them cried out, “The Catholic Church must be destroyed!” The young women trembled as they clutched the crucifix. It was snatched from them: “Why do you love this crucifix? We hate it!” Bishop Versiglia and Don Caravario realized that the time had come to witness to Christ even by the gift of their lives. Serenely, they prayed aloud and managed to confess to each other. Once more, the bishop tried to save his companion: “I am old, kill me; but he is young. Spare him!” Suddenly, five sharp rifle shots echoed in the air: the sacrifice had been made complete. “It is inexplicable,” said the murderers, “we have seen so many, and all were afraid to die. These two, on the contrary, died happy, and as to these (alluding to the young girls), they only wish to die.” In tears, the girls were forced to follow their attackers; the two boys were ordered to leave without looking back. The latter warned the authorities, who send squads of soldiers. On March 2, the soldiers reached the hideout of the bandits who, after a brief gunfight, fled, letting the girls go free: they were now invaluable witnesses to the martyrdom of the two missionaries. Recognized as martyrs, Bishop Versiglia and Don Caravario were canonized on October 1, 2000 by St. John Paul II.

“It is always because of his witness to the faith that a martyr is killed… The killers prove their hatred of the faith not only when their violence is unleashed against the explicit proclamation of the faith… but also when this violence is directed against works of charity in favour of one’s neighbor, works that objectively and truly have their justification and reason in the faith. They hate that which springs from faith, and they show their hatred of the faith which is at source of these works. This is the case of the two Salesian martyrs… They gave their lives for the salvation and moral integrity of their neighbor. They stood as shields to defend the persons of three young girls, students at the mission… At the cost of their blood, they defended the responsible choice of chastity made by these young people who were in danger of falling into the hands of people who would not have respected them. Theirs was a heroic testimony, therefore, in favour of chastity, which reminds today’s society of the value and the very high price of this virtue, the safeguarding of which, linked to the respect and promotion of human life, is well worth risking one’s life for, as we can see and admire in other shining examples in the history of Christianity” (St. John Paul II, ibid.).

May the Lord, through the intercession of the two holy martyrs, grant us the grace to meditate on their example and to imitate them, according to the particular responsibilities and circumstances of our lives!