May 2, 2018

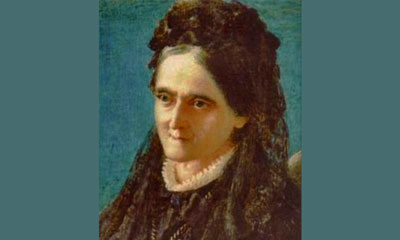

Blessed Louise-Thérèse de Montaignac

Dear Friends,

“In this nineteenth century, when there is so much division, frequently even within families, our mission is to unite… To firmly unite souls in a bond of true devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus.” These heartfelt words of Blessed Louise-Thérèse de Montaignac reveal the spirit of the foundress of the Oblates of the Heart of Jesus. “A daughter of the Church and a woman in the Church,” said Saint John Paul II, “Louise-Thérèse wished to serve the Lord and the Church, which are one. Animated by an ardent apostolic desire and sustained by a great devotion to the Heart of Jesus, she began the work in close cooperation with her bishop, with the priests of her parish, and with the lay faithful. She founded the Oblates who, through their union among themselves, were called to be agents of unity.” (Beatification Homily, Nov. 4, 1990)

Louise-Thérèse was born in Le Havre on May 14, 1820, to a profoundly Christian family which passed on the faith to her as a precious heritance. She was baptized the next day. Later, she would express her happiness at being a daughter of God and would celebrate each anniversary of her Baptism.

Louise-Thérèse was born in Le Havre on May 14, 1820, to a profoundly Christian family which passed on the faith to her as a precious heritance. She was baptized the next day. Later, she would express her happiness at being a daughter of God and would celebrate each anniversary of her Baptism.

Eternal life

On January 8, 2014, Pope Francis reminded us that Baptism “is not a formality! It is an act that touches the depths of our existence. … We, by Baptism, are immersed in that inexhaustible source of life which is the death of Jesus, the greatest act of love in all of history; and thanks to this love we can live a new life, no longer at the mercy of evil, of sin and of death, but in communion with God and with our brothers and sisters. … To know the date of our Baptism is to know a blessed day. The danger of not knowing is that we can lose awareness of what the Lord has done in us, the memory of the gift we have received. Thus, we end up considering it only as an event that took place in the past—and not by our own will but by that of our parents—and that it has no impact on the present. We must reawaken the memory of our Baptism. We are called to live out our Baptism every day as the present reality of our lives.”

Pope Benedict XVI noted that: “[in] the classical form of the rite of Baptism, first of all the priest asked what name the parents had chosen for the child, and then he continued with the question: ‘What do you ask of the Church?’ Answer: ‘Faith’. ‘And what does faith give you?’ ‘Eternal life’. According to this dialogue, the parents were seeking access to the faith for their child, communion with believers, because they saw in faith the key to ‘eternal life’. Today as in the past, this is what being baptized, becoming Christians, is all about: it is not just an act of socialization within the community, not simply a welcome into the Church. The parents expect more for the one to be baptized: they expect that faith, which includes the corporeal nature of the Church and her sacraments, will give life to their child—eternal life.” (Encyclical Spe Salvi, November 30, 2007, no. 10).

From her father, Raymond de Montaignac de Chauvance, a civil servant, and her mother, Anne de Raffin, Louise-Thérèse received the example of a life open to all. She was very close to her older sister Anna and her four brothers; she strove to make them happy. As a child, Louise was lively, spontaneous, always active: “I was made to love, so I desperately clung to all that was good or unfortunate.” Her spontaneous nature played tricks on her; she made lots of foolish mistakes and did stupid things, but her confidence disarmed all severity. The little girl loved to pray. One day, after a long search, she was found snuggled in a closet. “I was saying my prayers,” she said, and when asked the reason for this strange behavior, she explained, “It’s so that I don’t do wrong to God.”

In 1827, Louise went off to boarding school in Châteauroux, at the monastery of the Faithful Companions of Jesus, and then, for the following two years, at the des Oiseaux convent, run by the Daughters of Our Lady. Boarding school rules did not suit her in the least. During her first stay, she was still afraid of punishments. However, she received a grace at Christmas: in contemplating the crèche she discovered the touching mystery of a God-child, poor and suffering. She allowed herself to be taken by Him and began to love Him. At des Oiseaux, she was “so scatterbrained that she was always in penance and in tears.” In class, she “consented to study only because her companions were ahead of her.” In the chapel, she made commendable efforts to be recollected, but her good resolutions were always short lived. Louise would nevertheless always keep from these years the memory of happy days, in which her heart opened to God through her confessions as a child, her confidences to the Mother Superior “Mama Sophie,” and her first friendships. But, it must be acknowledged, her studies scarcely progressed. A change was needed; her parents entrusted her to her aunt, Madame de Raffin, who was also her godmother. Over the years, the affection that united the young woman and her goddaughter would turn into a profound closeness. For fifteen years, Louise lived in the Raffin home, sometimes in Nevers, sometimes in the country, without losing the bond with her family. “It was,” she would say, “one of the greatest graces of my life.”

A “reedy” girl

Her First Communion took place on June 6, 1833. “The little girl, the reediest there ever was,” she would say, had changed into a serious adolescent: “Since my First Communion, I have always remained under divine action.” The Eucharist became the center of her life. Madame de Raffin was a woman of tempered faith, but more energetic than tender. In school, Louise learned to control her natural energy without destroying its dynamism. She received a solid education, cultivated her artistic gifts, and started learning the role of lady of the house. Under the direction of Father Gaume (1802-1879), the director of the minor seminary, then vicar general of the diocese of Nevers, she likewise benefitted from a spiritual and doctrinal formation. Louise immersed herself in the Gospels, the Psalms, and read the Fathers of the Church and Saint Teresa of Avila, who became her main patroness. In 1837, when she returned to the des Oiseaux convent, she re-found the force of the faith that was the mark of this house, which radiated devotion to the Heart of Jesus. She was received into the Children of Mary. The Most Blessed Virgin, to whom “she confided all her sorrows” when she was a child, would from then on be her “teacher at every moment.”

On Christmas 1836, Louise-Thérèse came out of midnight Mass with her friend Camille de Breathier, who was murmuring the verse from Revelations: it is these who follow the Lamb wherever He goes (Rev. 14:4). Louise was overcome… To follow Jesus wherever He goes! From that moment on, the white light of the Lamb illumined her steps, tracing out the radiant path on which she strove to follow Him. On November 21, 1838, Father Gaume gave her permission to take the vow of virginity. Four years later, at the age of twenty-two, Louise-Thérèse was bedridden for ten months with a bone disease: the first health ordeal which would unite her more intimately with God. Madame de Raffin helped her to live this time of suffering in recognition that in all things, “God’s will is pure love.” Following this illness, her aunt asked Louise-Thérèse this blunt question: “If Our Lord said to you: ‘Do you wish to be attached to the Cross with Me up to the point of death,’ would you accept?” “Yes,” she replied, “and with all my heart!” She would fully live out this “folly of love that does not calculate, does not reason, that runs without resting after the Savior.”

A source for good

In the era following the Revolution, in a world contaminated by skepticism, many people’s faith was shaken. In response, fervent Christians dedicated themselves to God through a vow to the Sacred Heart. The formula of this vow, written by Father Roothaan, the Father General of the Jesuits, spread throughout France. From this source sprang a veritable spiritual renewal. Madame de Raffin had heard about it from Father Ronsin, the spiritual director for the des Oiseaux convent and, in 1841, she made the consecration. On September 8, 1843, Louise-Thérèse also made it. This vow is a response of our love to God’s first loving us, revealed by the Heart of Jesus, a response that engages the whole person in carrying out the Father’s plan. It was already the Oblation that would make the future Oblates. Forty years later, Louise-Thérèse could not recall the memory of this blessed day without profound emotion: “The vow to the Sacred Heart made my life. It was for me the source of all graces, of all joys.” To revive the faith, Madame de Raffin conceived a vast plan of uniting Christian women in devotion to the Heart of Jesus: “Little scattered pieces of coal,” she said, “can produce neither flame, nor warmth: gathered together, they can light a great fire capable of illumining and reheating the world.” Initially associated with the project, Louise-Thérèse took it over with the death of her aunt in 1845. She recalled its inspiration in light of the Gospel: “I came to cast fire upon the earth; and would that it were already kindled!” (Lk. 12:49). She dreamed of entering Carmel, but gave it up on Father Gaume’s recommendation: “Your vocation,” he told her, “is to carry Carmel into the midst of the world.”

The Revolution of 1848 shook France. Monsieur de Montaignac resigned as a civil servant. The family left Paris and settled in Montluçon, in the province of Bourbonnais, where its real roots were. Louise-Thérèse wondered how to awaken the faith in this city that was rapidly growing but marked by religious indifference. Every day, she spent two hours in prayer in the deserted parish church. Steadfast Christian groups were active in Montluçon, organized by a priest with a fervent heart, Father Guilhomet. Louise-Thérèse joined forces with him, and agreed to lead the congregation of the Children of Mary. She founded the orphanage of the Sacred Heart, and enlisted friends to teach catechism to the most abandoned. Having witnessed the abandonment of churches in the countryside, she established the Charity of Poor Churches, helped spread adoration of the Blessed Sacrament, organized retreats and endeavored to develop her aunt’s project—the association of Christian women. Thanks to support from her bishop, Bishop de Dreux-Brézé, and from her parish priest, these works spread in the diocese of Moulins and beyond. However, at this time the bone disease in her legs that Louise-Thérèse had been stricken with returned. For more than thirty years, suffering became her “inseparable companion”. Handicapped, she could move only with crutches or transported in a little carriage. She needed all the energy of love to remain tirelessly devoted to others, and to maintain the overflowing activity that characterized her life.

The first of the directors

In 1859, Mademoiselle de Montaignac met Father Gautrelet, a Jesuit, who in 1844 had founded the Apostolate of Prayer. Seeing his seminarians’ impatience to enter missionary life, this priest had told them: “Be apostles right now, apostles of prayer! Offer what you do each day in union with the Heart of Our Lord Jesus Christ, and for what He wants: the spread of the Kingdom of God for the salvation of souls.” A priest with a great deal of experience, Father Gautrelet would be Louise-Thérèse’s advisor for more than twenty-five years. With humility, he admitted: “I have great confidence in the direction of the Holy Spirit, the first of all directors!” That same year, he put his directee in touch with his confrere Father Ramière, who had just taken over the leadership of the Apostolate of Prayer. An ardent apostle of the Sacred Heart, Father Ramière launched Louise-Thérèse full sail into this movement. Louise-Thérèse saw in this spirituality the “most universal means for the sanctification of souls,” and found his organization to be “an excellent way to penetrate society.”

Speaking about Jesus’ friends, Martha and Mary, Pope Francis reminds us of the necessity of prayer: “Martha learned that the work of hospitality, though important, is not everything, but that listening to the Lord, as Mary did, was the really essential thing, the “best kind” of time … Do we have the Gospel at home? Do we open it sometimes to read it together? Do we meditate on it while reciting the Rosary? The Gospel read and meditated on as a family is like good bread that nourishes everyone’s heart. In the morning and in the evening, and when we sit at the table, we learn to say together a prayer with great simplicity: it is Jesus who comes among us, as he was with the family of Martha, Mary and Lazarus” (August 26, 2015).

At the beginning of the 1860s, Louise-Thérèse began the construction of a beautiful chapel in the heart of Montluçon, to “unceasingly remind us of the love of the heart of Jesus.” Dedicated on May 31, 1864, it would become the chapel of the mother house of the Association of Christian Women. The same year, an attempt was made to unite this organization with the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart in Issoudun. But in 1874, the Association broke off, and became the Pious Union of the Oblates of the Heart of Jesus, under its own rule approved by the Bishop of Moulins. These years were fruitful: the Christian women consecrated by vow to the Heart of Jesus were growing in number. In December 1875, Louise-Thérèse was appointed secretary general of the Apostolate of Prayer. Her correspondence—more than 1800 letters have been preserved—testifies to the quality of these relationships. Very practical, she entered with her innate common sense into the most minute details of material life, the organization of houses, health; and quite naturally, with tact and discretion, she became a spiritual guide who taught how to live in the light of faith. Strong friendships, born from these exchanges, marked her life: “Saint Teresa of Avila,” she said, “greatly loved her friends and this has always encouraged me to warmly love my friends.”

Two different forms

In Montluçon a small team surrounded Louise-Thérèse. These first companions led a common life of prayer and hospitality, for they received many individuals. The chapel was a center for retreats, for spiritual encounters. Thus a first community took shape. Soon, a House was founded in Paray-le-Monial, then another in Paris. At the start of the 1880s, the future face of the institute took shape—two different forms of the Oblation for women destined to serve God and neighbor were proposed. Some, married or not, would remain in their environment, harmonizing their family obligations with quite varied forms of apostolate. They formed “Re-unions” in the true sense of the word: “re-uniting,” that is meeting again, in a group regularly to pray together and practice fraternal charity; these are secular oblates. The others made vows of religion, poverty, chastity, and obedience, in accordance with Louise-Thérèse’s inspiration. These professed oblates lived in community in the Houses, which were houses of prayer, intended first and foremost for the revitalization of the secular oblates. Each of the Houses took on one or more apostolates.

On May 17, 1880, Louise-Thérèse was elected superior general. Her role was to ensure “unity of spirit and tendencies, freedom in works and deeds, whether collective or individual.” The oblates’ chapter defined the mission of the institute: “To unite souls strongly through the bond of a true devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, drawing them to prayer, reparation, and devotion in union with Him, and manifesting their love in the performance of works for His glory.” For the foundress, devotion to the Heart of Jesus is a life of union and conformity with Him Who is eternal life which was with the Father (1 Jn. 1:2). “Our primary code of life,” she said, “is Jesus’ priestly Prayer,” which appears in Chapter 17 of Saint John’s Gospel: that they may be one even as we are one. On October 4, 1881, this mission was officially recognized by Pope Leo XIII. The communities multiplied: Lyon, Montélimar…

In the last years of her life, Louise-Thérèse experienced an even greater intimacy with Our Lord, and grew in her service to others. Restricted to her chair or sickbed, she burned with a fervor more infectious than ever. “I am,” she gaily said, “like a young, frisky horse that has all four hooves tied down, but is whipped to make it walk. … When I see all the work that Our Lord presents to me, I wish to do everything, to undertake everything.” In Montluçon, newcomers had taken the place of the workers of the first hour. Louise-Thérèse made formation of these daughters a priority, for they would have to pass on that which they had received, as in a family. Saint John Paul II reminded parents: “To hand on to your children the faith you received from your parents is your first duty and your greatest privilege as parents. The home should be the first school of religion, as it must be the first school of prayer” (Ireland, October 1, 1979).

No barrier

Louise-Thérèse invites us to “an intimate communication, continual and full of love, with God, to a respectful and filial familiarity… God must be the breath of our soul, we must move and act only in Him… True contemplation consists of having one’s mind and heart united with Jesus, speaking, acting, thinking like Him. What life could be more active and yet more contemplative than His? Always united to His Father, He is our model, our sole guide. Such are the fervent and energetic souls who are called to make the greatest progress in contemplative life. Such are the ones who best carry out Our Lord’s plans. What is the use of contemplating a model if one does not have the energy to reproduce it? The active soul acts on the fruit of one’s prayer, puts into action the lights it has received. It works in prayer, in humility, in devotion, in self-sacrifice. This is the true way of putting the life of Jesus into practice.” If someone close to her was a little stressed by external occupations, she would calm her: “You work for God, without doubt, but one must work in God.” The formation she gave was completely directed toward the freedom of love: “There is no barrier between Jesus and the oblate. Every soul goes where the Spirit leads it; Love is its only guide.” She also demanded that all be treated with respect, attention paid to each and to what God wanted of each. Returning to this humility that is the welcome of God, that He has a place for all, she noted, “Love dies where there is no humility.”

Christmas was a special time each year for Louise-Thérèse. In 1882, as this feast drew near, she invited the youngest of the oblates to follow “this little Child Who calls us to His crèche to lead us to Calvary where His Heart is always open.” And she vigorously insisted: “How could we resist Him? He shows Himself always to be the Savior. Let us be it with Him as his littlest disciples.” This sums up Louise-Thérèse’s entire life. Struck by the person of Jesus in the mystery of His Incarnation, she handed herself over to Him so that He might live in her, so that He might continue His mission in her. By patiently enduring her intensely painful illness, which left her little respite, she united herself ever more closely with the Savior’s Passion. “If You wish for me to continue to suffer, I will not complain,” she told Him in 1881. She nevertheless had to undergo a night of the spirit: “I see nothing, I feel nothing. But I have faith in You, and that is enough for me.” During the last hours of her life, she relied upon her Savior: “I am counting on Divine Mercy, I will say: I have loved.” On June 27, 1885, she died as she was replying simply to the name of Jesus that someone close to her was saying: “My all!” The institute soon saw a rapid expansion. The secular oblates’ first foundations were established abroad: Portugal (1887), El Salvador and Poland (1894), and Nicaragua (1903). Today, the institute is also established in Belgium, South America and Africa.

“Let us ask Blessed Louise-Thérèse of Montaignac de Chauvance to help us recognize the love of the Heart of Jesus and to remind men and women of it unceasingly, as she did so well during her life” (Saint John Paul II).