February 22, 2018

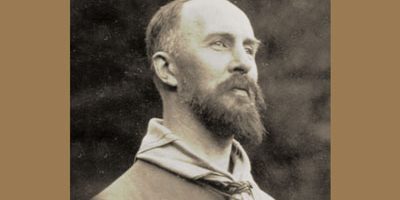

Father Sevin, sj

Dear Friends,

In the 1920s, the youth who came to the camp at Chamarande, in Île-de-France, to be trained as scout leaders or guides were struck, when they arrived, by the presence of an extraordinarily charismatic priest—a bearded, blue-eyed Jesuit, dressed in a khaki cassock. The “camp master,” as was his title, taught them the “secular” subjects such as how to cut down trees and build huts, to be sure, but above all he introduced them to spiritual combat and led them to a life of intimacy with the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Who was this priest whose enchanting smile and deep gaze no one could forget?

On September 7, 1882, Jacques, the eldest son of Adolphe-Marie and Louise Sevin, was born. Adolphe Sevin, a regular practitioner of the Exercises of Saint Ignatius and very involved in the Catholic social sphere, frequently participated in local Catholic conferences, including one on “the best ways to fight against pornography and licentiousness in the streets.” In this fervent family, prayer and leading a truly Christian life were taken very seriously. Jacques spent his early childhood in Dunkirk, a large French port on the North Sea. He dreamed of becoming a sailor, while his father, a businessman in the textile industry, directed him towards trade. But God had other plans for him. In 1888, the Sevins moved to Tourcoing, a city outside Lille that at the time was a center for the textile industry. In 1892, Jacques was sent to the Jesuit school in Amiens, where his father had been a student. Three years later, he lost his brother Joseph. This trial broke his heart, but inspired in him this heroic cry: “For this cross, my God, thank you!”

On September 7, 1882, Jacques, the eldest son of Adolphe-Marie and Louise Sevin, was born. Adolphe Sevin, a regular practitioner of the Exercises of Saint Ignatius and very involved in the Catholic social sphere, frequently participated in local Catholic conferences, including one on “the best ways to fight against pornography and licentiousness in the streets.” In this fervent family, prayer and leading a truly Christian life were taken very seriously. Jacques spent his early childhood in Dunkirk, a large French port on the North Sea. He dreamed of becoming a sailor, while his father, a businessman in the textile industry, directed him towards trade. But God had other plans for him. In 1888, the Sevins moved to Tourcoing, a city outside Lille that at the time was a center for the textile industry. In 1892, Jacques was sent to the Jesuit school in Amiens, where his father had been a student. Three years later, he lost his brother Joseph. This trial broke his heart, but inspired in him this heroic cry: “For this cross, my God, thank you!”

“You have done well”

Jacques wanted to take the entrance exam for the Naval School, but his father asked him to take over the family business instead. The young man consoled himself for the dryness of his studies by passionately devoting himself to poetry, which would remain a major thirst in his soul for the rest of his life. In 1900, he finished high school and began a degree in English. In the midst of the crises of adolescence, Jacques let Jesus Christ form his soul and strengthen it with His grace for the battles against sin and sensuality, and to dedicate his life generously. In 1895, the first divine call echoed in his heart. Retreats taken with the Jesuits in 1897, 1898, and 1900 led him to make his choice: he entered the Society of Jesus. He freely sacrificed his dream of becoming a sailor to follow Christ’s call. He wrote in his “election of a state of life” the reasons for his choice: “To save my soul. To save others’ souls. To have a rule, superiors, and community life. To not be vulgar.” On September 9, 1900, while in novitiate in Saint-Acheul close to Amiens, Jacques informed his parents of his decision. His father replied: “You have done well not to doubt us. God will do with us what He wants. We would not dare want Him not do with you as he wishes.” His mother added tenderly, “The thought that in objecting to your plan I would cause your unhappiness, even in this world, strips me of the courage to be opposed to it. So be happy on this path, and I will be too.”

In 1901, a law requiring religious congregations to have the permission of the government forced the Jesuits to go into exile. The novitiate in Saint-Acheul was moved to Arlon in Belgium. Jacques would not see France again until 1919. Possessing a somewhat rigid piety at the beginning of his novitiate, he soon regained his natural gaiety as well as his poetic vigor, which he used in the service of piety, especially to express devotion to Mary. He made strides in spiritual combat under the direction of Father Louis Pouillier, whose spirituality revolved around the mystery of the redeeming Incarnation. On September 5, 1902, Jacques Sevin made his first vows and received a crucifix that he would keep with him until the day he died. Having received the order to pursue his degree in English, Jacques went through a difficult period spiritually while teaching this language in several Jesuit schools, but showed himself talented as an educator. On August 2, 1914, he was ordained a priest with thirty other Jesuits. But when the First World War broke out, Jacques found himself cut off from France by the advance of German troops. Forced to remain in Belgium, in 1916 he was appointed to the school in Mouscron, a stone’s throw from the French border that was closed by the occupying power. He could not even see his parents who were living in Tourcoing, five kilometers away. In February 1917, he made his final vows.

Avoiding every misstep

Now Father Sevin, he began to carry out a new plan: to adapt for Catholic youth the Boy Scout movement founded in England in 1907 by Robert Baden-Powell. In 1913, he had obtained permission to study the implementation of English scouting at the camp in Roehampton. Captivated, from then on he hoped to import this movement to Belgium, but he had to take into account the strong reservations of many priests, who criticized the religious neutrality of English scouting. Indeed, as a Protestant, Baden-Powell had given his Boy Scouts movement an interfaith character; it seemed a Catholic educational effort could not follow this model. So Father Sevin wrote a book in which he responded to these objections while developing his ideas on scouting, but not without asking for the opinions of his superiors. Indeed, he wanted “to avoid every misstep and fully have the grace of obedience.” On February 8, 1918, his superior approved the project, and specified that he must strive “to form a profoundly Catholic group.” In fact, Father Sevin’s intent was to make use of Baden-Powell’s fundamentally sound educational methods, while complementing them with a profound Catholic formation for youth. On the 13th, the first meeting of the leaders took place in Mouscron, and the first scout promises were made. After Belgium was liberated in 1919, the movement took off, and crossed the border that was now reopened. The “Scouts of France” were born in Lille with several troops of boys.

Soon, his superiors sent Father Sevin to Paris to work full-time on scouting. He partnered with Canon Cornette, a parish priest of Saint-Honoré-d’Eylau who was paralyzed in both arms but full of enthusiasm, and Édouard de Macedo, a layman with a charism for education. During a jamboree (a world meeting of scouts) in England, Father Sevin forged ties with other Catholic scout organizations in various European countries; from this was born the International Office of Catholic Scouts. In 1921, Cardinal Dubois, the archbishop of Paris, approved the Catholic Federation of the Scouts of France, of which Father Sevin was secretary general. In these first years, ninety percent of scouts came from working-class families, which the parish youth clubs had found very difficult to reach. Later, the movement would comprise mostly children from more privileged backgrounds, which Father Sevin, who had wanted to go first to those on the fringes, would always regret. “The children we claim as especially ours, are those that existing organizations do not, or no longer, want.”

In November 1921, Father Sevin was assigned to the Jesuit residence in Lille. This measure brought with it the opposition of certain priests who were hostile to scouting, and also complicated his task, as it distanced him from Paris. Indeed, the laws of the movement give a primary role to troop leaders, who are lay people, while asking chaplains to confine themselves ordinarily to their spiritual duties. This correct independence of lay people in temporal matters, like the organization of a camp, revives an idea that was relatively uncommon at the beginning of the twentieth century. However, Father Sevin never lost sight of the ultimate aim of Catholic scouting: to lead young people to a fervent life of union with Jesus Christ, so as to save their souls. In 1922, during the Exercises of Saint Ignatius that he preached to thirty-two scout leaders, he gave them these instructions: “Through prayer and generosity, arrive at a point of intimate contact with Our Lord.” That same year, the first edition of the magazine The Scout appeared, intended for all male and female scout leaders (a scouting branch for girls, The Guides of France, had also been founded).

The Gospel, studied in depth

In 1923, the owners of the château de Chamarande, 40 kilometers south of Paris, made the vast wooded park on their property permanently available to the Scouts of France. At “Cham,” for ten years Father Sevin—who had received praise and encouragement from Baden-Powell—would personally lead countless training camps for male and female scout leaders, deeply touching a thousand leaders. He gave all of them the goal of holiness, a holiness that must rest on “the Gospel, read, reread, and studied in depth.” The construction of an immense chapel was launched at the outset, where, starting in 1929, everyone could come to adore Jesus present in the tabernacle. Father Sevin celebrated Mass outdoors every day, in an open shelter. Mass attendance during the week was not strictly required, but no one would have wanted to miss it, so impressive and edifying was Father Sevin’s celebration of it. The themes he touched upon most during training camps were the scouting spirit, scouting and religion, the state of grace, purity, fidelity to the duties of one’s state, prudence, the meaning and the lessons of the Cross, teamwork, confidence, truth, authority, selflessness, and above all, the example of and openness to the beauty of creation, God’s handiwork. Very much influenced by the ideal of chivalry, he exclaimed, “The proudest epic is to conquer one’s soul and become a saint.”

Father Sevin translated Baden-Powell’s Scout Law into French, and adapted it by prefacing it with three principles: (1) The scout is proud of his faith, and submits to it his entire life. (2) The scout is a son of France, and a good citizen. (3) The scout’s duty begins at home. Taking inspiration from the Divine Office, through which the Church sanctifies the various hours of the day, Father Sevin likewise composed prayers for various times of the scout’s day. We also owe to him a number of hymns that have become classics; e.g. The Promise Song, and Our Lady of the Scouts. He used a frequent image from the Bible (cf. Gen. 12:8), saying that one day every man must “fold up his tent.” Father Sevin wanted this precious moment of death, which ushers each of us into eternity, to be prepared for by many small renunciations woven into the scout’s day: each sacrifice, each “b.a.” (bonne action, or good deed), is a little death to self that sets us on our way to eternal life.

Speaking to 4,000 scouts from Italy on September 4, 1946, Pope Pius XII said: “Your organization’s motto is Estote parati, ‘be prepared’ (cf. Mt. 24:44), that is, always be ready to do your duty. We would like to give these words an even greater and more profound meaning: be ready at all times to consciously do the will of God and observe His commandments. Be ready above all for the moment, known by God alone, when the Lord will call you to render an account of the talents that have been entrusted to you.” Similarly, the Second Vatican Council teaches: “For a true education aims at the formation of the human person in the pursuit of his ultimate end and of the good of the societies of which, as man, he is a member, and in whose obligations, as an adult, he will share” (Declaration on Christian Education).

Going against the current

The scouts’ flag reproduces the Jerusalem Cross, a Greek cross potent. The four “T’s” oriented toward the four cardinal points symbolize the universality of the Redemption. This cross is juxtaposed with the fleur-de-lis, a compass symbol that indicates the right direction. Saint John Paul II, speaking to a gathering of European scouts in Viterbi on August 3, 1994, clarifies what the right direction is: “In a world that offers easy pleasures and deceitful illusions, we must be able to go against the current, inspired by the essential moral values, the only ones that can bring about a happy, prosperous, and peaceful life.”

The power of Father Sevin’s influence came from the way his actions matched his words. He taught that one must not ask others to give what one has not oneself already given to God. Others were inflamed with the interior fire that blazed within him; prayer, adoration, and silence became for these young leaders the indispensable cornerstones of a structure that, without them, would be exposed to the erosion of activism and naturalism. Among many other benefits, the camps in Chamarande became incubators for religious and priestly vocations—more than four hundred during the first ten years of its founding. Yet the Camp Master did not want too much seriousness—scouting was to remain fun, and young people would sanctify themselves while enjoying the fun. Joy reigned in the camps, even on rainy or dreary days. Sports held an important place, as they should. “Sport is a competition, a race to obtain a crown, a cup, a record. But, through our Christian faith, we know that what has the greatest value is the ‘crown that does not fade,’ ‘eternal life’ that we receive from God as a gift, but which is also the result of a daily conquest in living out the virtues” (Saint John Paul II, April 12, 1984).

As chaplain for Troop Nine in Lille, Father Sevin often took his boys to the seaside heliotherapy center at Berck Beach, where many seriously ill youth received care. In 1927, he founded a scouting group there comprised of sixty sick or disabled youth. This “Extension Scouting,” would be spread throughout the world for youth whose health does not allow them to participate in traditional scouting, with its demanding outdoor activities.

A very small movement

But, among the lay scout leaders in France, not everyone appreciated Father Sevin’s personality. He was criticized for going beyond the role of a priest and leading the movement towards mysticism. On the other hand, he was accused of religious indifferentism because of his connection with the Protestant Baden-Powell. Denounced to the Holy Office, Father Sevin was summoned to Rome in 1925. He easily defended himself, and Pope Pius XI expressed to him his confidence and encouragement for his movement. Father Sevin drew from this warning a lesson in humility: “We are a very small movement in Catholic France, and even smaller in the Holy Church.” And he corrected in his writings certain expressions that were insufficiently consistent with Catholic doctrine and faith. In spite of this, opposition and dissenting voices continued. On March 15, 1933, Father Sevin saw his responsibilities as director of formation for leaders, director of the magazine The Leader, and international director, withdrawn, on the grounds that he was unnecessarily filling roles more appropriate for lay people. He would subsequently be removed from all responsibilities with the Scouts of France, and in the end, even from his duties as chaplain for the Ninth Troop of Lille. In reality, these decisions had their origins in enmity and jealousy aroused by Father Sevin’s personal charisma. Father Sevin deeply suffered the bitterness of this definitive removal at the age of fifty-one from the movement he had founded. Until 1939, he continued a very effective ministry in Lille, then was sent to Troyes to fulfill the honorable role, from 1940 to 1946, of superior of the Jesuit residence, which he would save from disappearing during the difficult times of the German occupation.

Affected by this hostility he did not understand, and wounded by the behavior of people he thought he could count on, Father Sevin suffered in private, abstaining from all public recrimination. He applied the teaching he had given to all the leaders during the camps in Chamarande: “We must accept what happens to us, even if we sense that others will think we’ve been taken down a level.” He forgave those who had treated him unjustly, and even succeeded in renewing friendly relations with them, often when they were sick or at the end of their life.

In 1935, during a retreat he was preaching, Father Sevin met Jacqueline Brière, a Cub leader with whom he formed a spiritual circle for girls. Nine years later, a contemplative and missionary congregation, the “Holy Cross of Jerusalem,” would be born from this group. As the author of the statutes and spiritual Father, in 1950, Father Sevin had to offer to God a final detachment: his Provincial asked him, on behalf of the Father General, to turn over his duties as director and confessor of the Holy Cross of Jerusalem to another. That very day, he replied, “The V.R.F. General can count on my absolute obedience, without negotiation. I have wanted to instill this spirit in my daughters too much not to try to give an example of it.” Today, the congregation of the Holy Cross of Jerusalem has seven houses in various countries. On the occasion of opening the process for Father Sevin’s beatification, Father Kolvenbach, at the time Jesuit Superior General, said of him: “Unexpectedly given notice to yield his place, Father Sevin accepted to return to the shadows. Wounded, to be sure, but with no bitterness or resentment, he would make Saint John the Baptist’s attitude his own: He must increase, but I must decrease (Jn. 3:30). And that is where his true greatness lay.”

At all costs

To youth, Father Sevin taught the promises that the Sacred Heart of Jesus gave to Saint Margaret Mary: “Lukewarm souls (who practice this devotion) will become fervent…they will succeed in all their endeavors.” On June 16, 1950, he wrote a final act of consecration that begins: “O beloved Jesus, since I wish to be Yours, take me and make me holy at all costs, even in spite of myself. What is impossible to my poverty is but a game to Your mercy; for if I may rightly despair of myself, I know that I can never hope too much in Your power and Your goodness.”

A bard of Our Lady, Father Sevin wrote numerous poems, canticles, and meditations in honor of Mary. He entrusted the purity of the scouts to the protection of the Immaculate Virgin; the tenth article of the Scouts’ Law states, “A scout is pure in his thoughts, words, and actions.” And to her who Christians ceaselessly ask for the grace of a good death, he prayed:

“Ave Maria!

When my hour comes

Take pity on him who prayed so much to you

And in your love let me die

Saying again Ave Maria!”

In a poem from 1913, Father Sevin addressed Sister Therese of the Child Jesus, who had so profoundly marked his spirituality:

“Give us, when, weary of the steep road

We no longer feel anything but the weight of the effort

‘Little Saint,’ who is followed with such great love,

The generosity to smile at life

That we might have the sweetness of smiling at death.”

Struck with bronchitis in February 1951, Father Sevin spent his final months on earth at Boran-sur-Oise in a convent of the Sisters of the Holy Cross. He progressively weakened and died on July 19 after a long agony during which he edified those around him with his peace and his abandonment to Providence. In his last moments, he gripped in his hands the large crucifix received at his profession, murmuring, “My companion! It’s my companion!” On May 10, 2012, Pope Benedict XVI recognized his heroic virtues, the first step towards beatification.

Father Sevin had given the scouts and guides the “Scout Prayer” attributed to Saint Ignatius of Loyola, for each to make their own:

“Lord Jesus,

Teach us to be generous, to serve You as You deserve,

To give and not count the cost, to fight and not heed the wounds,

To toil and not seek for rest, to labor and not look for any reward

Save that of knowing that we do Your Holy Will.”