July 11, 2018

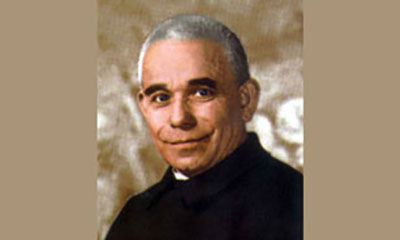

Saint John of Britto- sj

Dear Friends,

One day in 1663 or 1664, the Infante of Portugal, Don Pedro, heir to the crown, accompanied by his pages, arrived at the door of the Jesuit novitiate in Lisbon, Portugal. All the novices rushed to greet the illustrious visitor, except for John de Britto. John who, as a page had rubbed shoulders with the future king, eventually arrived wearing an apron—he had been busy caring for a servant of the community, stricken by an epidemic. “I’m charmed,” exclaimed the prince in an outburst of faith, “to find you in the service of this new master! You will earn greater rewards from him than you ever could from me…”

John de Britto was born on March 1, 1647, to a family of Portugal’s high nobility. His father, Don Salvador de Britto Preyra, would be viceroy of Brazil. When the child fell gravely ill, his mother, Dona Beatrix, consecrated him to Saint Francis Xavier, the great Jesuit missionary to India and Japan, to obtain his cure. At the age of nine, John entered the court in Lisbon as a page. During his adolescence, he was noted for his angelic purity, which was put to the test amidst the young and rich nobles. Indeed, the spectacle of the court led him to withdraw from the world, and on December 17, 1662, at the age of sixteen, he entered the Society of Jesus. Sadly surprised, his mother nevertheless accepted his decision. During his philosophy studies in Coimbra (1666-1669), John asked the Superior General of the Society of Jesus to be sent to the missions in the Indies, for, he stated, “Saint Francis Xavier cured me, and he is calling me to the Indies.” He was ordained to the priesthood in Lisbon in February 1673, and his superiors decided to send him to Madurai, a region in southeast India. In spite of his mother’s opposition, and against the advice of his doctors, the young Jesuit departed Lisbon in March, along with twenty-seven confreres, under the leadership of Father Balthazar da Costa, a veteran of the Indian missions.

John de Britto was born on March 1, 1647, to a family of Portugal’s high nobility. His father, Don Salvador de Britto Preyra, would be viceroy of Brazil. When the child fell gravely ill, his mother, Dona Beatrix, consecrated him to Saint Francis Xavier, the great Jesuit missionary to India and Japan, to obtain his cure. At the age of nine, John entered the court in Lisbon as a page. During his adolescence, he was noted for his angelic purity, which was put to the test amidst the young and rich nobles. Indeed, the spectacle of the court led him to withdraw from the world, and on December 17, 1662, at the age of sixteen, he entered the Society of Jesus. Sadly surprised, his mother nevertheless accepted his decision. During his philosophy studies in Coimbra (1666-1669), John asked the Superior General of the Society of Jesus to be sent to the missions in the Indies, for, he stated, “Saint Francis Xavier cured me, and he is calling me to the Indies.” He was ordained to the priesthood in Lisbon in February 1673, and his superiors decided to send him to Madurai, a region in southeast India. In spite of his mother’s opposition, and against the advice of his doctors, the young Jesuit departed Lisbon in March, along with twenty-seven confreres, under the leadership of Father Balthazar da Costa, a veteran of the Indian missions.

Missionary by nature

“Jesus, the very first and greatest evangelizer… continually sends us forth to proclaim the Gospel of the love of God the Father in the power of the Holy Spirit,” Pope Francis reminds us. “The Church is missionary by nature; otherwise, she would no longer be the Church of Christ, but one group among many others that soon end up serving their purpose and passing away… The Church’s mission, directed to all men and women of good will, is based on the transformative power of the Gospel. The Gospel is Good News filled with contagious joy, for it contains and offers new life: the life of the Risen Christ Who, by bestowing His life-giving Spirit, becomes for us the Way, the Truth and the Life (cf. Jn. 14:6)… In following Jesus as our Way, we experience Truth and receive His Life, which is fullness of communion with God the Father in the power of the Holy Spirit. That life sets us free from every kind of selfishness, and is a source of creativity in love” (Message of June 4, 2017, for World Mission Day).

In September the missionaries arrived in Goa, a Portuguese possession on the west coast of India. There, John immediately went to give thanks at the chapel where the miraculously preserved body of Saint Francis Xavier is venerated. He learned the Tamil language without delay, and the following year, left for Madurai. The young missionary first acquainted himself with the country, in particular with Hinduism and its caste structure, with its rigid and complicated rules. He realized that winning over the highest caste, that of the Brahmins, was key to converting the country. Yet his zeal also led him to the most marginalized, the pariahs or outcasts, whom he visited at night. In order to preach the Gospel to the educated, taking account of positive elements of wisdom found in the Veda, John studied the sacred books of India, written in Sanskrit. Like his predecessor, Father Roberto de Nobili, who died in Madurai some fifteen years earlier, he adopted some of the rules of the ascetic life of the Hindu religious which did not contradict Christian teaching. He even dressed as a “Pandara Swami”, wearing the distinctive garb of those who renounce the world. This austerity seemed excessive to many of his confreres, and he also was reproached for practicing certain Indian rituals. But on the occasion of his beatification, Pope Benedict XIV would free him of all suspicion on this count: “These customs are merely common practices of civil life, and thus without any particular religious meaning.”

Saved by charity

Despite his poor health, John de Britto refused to make use of the horse he was offered, going about on foot instead. Morning and evening, rice was his main meal. In 1676 and 1677, terrible floods resulted in many victims and great destruction. The missions were not spared—the Fathers had to move several times, always beginning again from nothing. Moreover, war raged continuously, accompanied by famines and persecutions against the Christians. During an epidemic of the plague, devotees of Shiva, one of the three principal gods of India, tried to stir up the people against the missionary by blaming him for the scourge, but the charity of the priest, who was caring for the plague victims, managed to prevent the worst.

The missionaries were helped by a number of native catechists. The faithful were widely dispersed, but brave and persevering. They sometimes walked as far as sixty kilometers to receive the sacraments. John’s preaching was validated by miracles, such as, for example, the resurrection of a baptized child struck by lightning. “These graces are so frequent that our Christians are used to them,” observed the missionary. They greatly facilitated the mission, particularly in abolishing polygamy, at that time common among the elite of the country, and which was a great obstacle to evangelization. Nevertheless conversions took place, at the cost of sending away several spouses. However, the pagan authorities’ fierce opposition to the preaching of the Gospel forced Father de Britto to move and, for six months, to evangelize in another region of India. During the year following his return, he baptized some 1,200 pagans. Two years later, at the age of thirty-eight, he was appointed superior of the mission in Madurai. He would remain there from 1685 to 1686. However, slander against him had reached Rome and had already resulted in the Father General removing him from the mission, but a providential change of Provincial allowed him to remain in Madurai. One of his missionaries would say of him: “He greatly multiplied the Christian communities… Once named superior, he used his authority only to relieve his brothers, at his own cost. He always reserved for himself the most unpleasant tasks.” Continuously hunted by the pagans, he had to lead a semi-clandestine life, amidst persecution and civil war. Some Christians were martyred, others died of starvation in the jungle where they had been forced to flee. However, unhoped for assistance also came from sympathetic pagans.

In 1686, Father de Britto’s success in evangelizing Miramar, a neighboring kingdom to Madurai, irritated the Brahmins, who then plotted his murder. A hired gang set off for the very new Christian settlement where the Father was. John and his catechists were beaten with sticks, chained, and imprisoned. They were promised their freedom if they agreed to worship Shiva, or simply receive Shiva’s ashes on their foreheads, a gesture that in fact would be apostasy, and they unanimously refused. Father John de Britto was condemned to death for having preached a foreign religion and having refused to invoke the Hindu god. The same day he was whipped and left for dead. A merciful pagan treated his wounds, and the captives were returned to prison. Once again a death sentence was pronounced. The condemned men then said a Rosary in thanksgiving. Father de Britto was concerned about the effect that so many difficulties could have on the neophytes in the region: “Do not fear men”, he told them (cf. Lk. 12:4t.), “The heavenly Father will care for you. If He allows you to be tormented, He will first give you the courage, then eternal glory.” On July 30, 1686, John managed to send a letter to his Jesuit superior: “We are happy and we bless the Divine Will that deigns to grant us the grace to shed our blood for His holy Law.” The prisoners were held captive for a month in the royal stables. Wishing to take advantage of Father de Britto’s state of exhaustion, some Brahmins challenged him to theological debate, but they soon had to give up. In the end, the prisoners were freed, without knowing why.

Extreme surprise

Father John’s superiors then decided to send him to defend the interests of the Indian mission at the royal court in Lisbon. But he first had to pass through Goa to negotiate with the Portuguese authorities some delicate points about who had control over the Indian missions, a right long ago accorded by the Holy See to the King of Portugal. The negotiations failed, and Father de Britto set sail for Europe. He arrived in Lisbon in September 1687. The news of his having been condemned to death had spread, so the crowd that greeted his ship was very surprised to see him disembark. The missionary’s accounts everywhere aroused such enthusiasm that a number of priests and students asked to follow him to India: “We cannot close all the colleges just to satisfy these noble desires!” exclaimed one of the superiors of the Society. Father de Britto paid a visit to King Don Pedro II. Overcome by the sight of his childhood friend, now an emaciated missionary, aged and scarred by the tortures he had endured, the king tried to keep him in Portugal to entrust him with the education of his children. The missionary refused, asserting that the needs were much greater in India. When called upon to preach, he often stressed the scandal caused in India by the misconduct of some of the Portuguese there. When they did not act with justice, selflessness, and loyalty, he declared, any proclamation of Christianity was perceived as hypocritical. His speech brought about many conversions, for his virtue, far from being dour, attracted others through its gentleness and extraordinary kindness.

Fear of honors

The missionary took to the seas again on March 19, 1690, in the company of nineteen religious, most already priests. Arriving in Goa in November, he received a triumphant welcome. After three months, he went to Madurai, where he took up his itinerant apostolate again. Out of prudence, he never stayed long in the same place. However, the king of Portugal had not given up on his idea; he schemed to have the Superior General of the Jesuits send John back to Portugal, but in vain. The king then thought of having him raised to the honor of archbishop, in India. But Father de Britto, who had a greater fear of honors than of persecution, managed to have this plan quashed. He was then entrusted by his local superiors with a three-year visit to Madurai, where the persecution was intense. He wrote to a brother coadjutor: “Pray much for me, for this land is a very difficult field of action. I have great need of very special assistance from Heaven to succeed. The conversions are many; even more are those who are waiting for me to baptize them. If I am imprisoned again, I hope that this time I will not escape death.” A thought was always present to him: “I will have done nothing for God until I have shed the last drop of my blood.” Nevertheless, he made every effort to observe a healthy caution.

Having arrived in a war zone, constantly patrolled by soldiers, he had to live in the woods: “It is already four months that I have been banished to the woods, living in the midst of tigers and serpents that are found there in great number,” he confided to a bishop. “My abode is in a tree.” Nevertheless, he found the means to maintain a correspondence with his superiors and others. In one locality, in a fortnight he heard a thousand confessions and baptized four hundred well-prepared catechumens. Taking advantage of a lull in the fighting and persecutions, he baptized eight thousand catechumens in the space of eighteen months. He also had to regularize marriages, reconcile apostates, etc. The conversions multiplied, reaching the high castes and the relatives of the king. But, by that very fact, the danger increased. “The second Sunday of Lent,” wrote Father de Britto to a confrere, “they attempted to seize me, but I had left a half-hour before the enemies arrived. They captured a baptized Christian whom they overwhelmed with blows and mistreatment, to force him to renounce his faith. Thanks to God the neophyte remained unshakable.” And to another: “I hear confessions, baptize, and administer the sacraments more than ever. From all sides they ask me for catechists. O my Father, compared to all this, what are all the grandeurs of Europe?” Nevertheless, the neophytes were frightened by the constant threat of persecution. John de Britto sought a propitious occasion to meet with the king of Miramar to try to get from him an edict of tolerance.

A personal offense

Nevertheless, a royal prince, Tadiyathevar, at first an enemy of the missionary, had fallen seriously ill and, having exhausted all human remedies, asked the missionary to cure him. Father de Britto first sent a catechist to make sure of the sincerity of the request, and to propose Baptism to him instead. In spite of the risks of a new persecution from the king, in the end he agreed to meet this prince. The prince, a polygamist, had five wives, and could not receive Baptism before he came into compliance with the Christian law on marriage. But sending away unlawful wives risked antagonizing the king himself, who would see in it a disruption of the established social order in his kingdom. The prince hesitated; nevertheless, he allowed the missionary to organize in the prince’s palace a magnificent ceremony, during which two hundred catechumens were baptized, and Communion given to hundreds of already baptized subjects. Awestruck, the prince finally let himself to be persuaded, and sent away all his wives after having provided for their needs, except for the first whom he considered his lawful spouse. He then received Baptism, along with his lawful wife, on January 6, 1693. But one of the repudiated wives was the niece of the persecuting king, and she rushed to her uncle and complained to him. Enraged, the king considered her having been sent away as a personal offense.

Father John de Britto’s steadfastness on the sanctity of marriage has led to his often being compared to Saint John the Baptist, who paid with his life for his adherence to God’s law, in particular the absolute prohibition of any adulterous union.

In the encyclical Redemptoris Missio, Saint John Paul II reminds us that obeying the teachings of the Gospel leads man to true freedom and to the authentic love to which he aspires: “The Church offers mankind the Gospel, that prophetic message which responds to the needs and aspirations of the human heart and always remains ‘Good News.’ The Church cannot fail to proclaim that Jesus came to reveal the face of God and to merit salvation for all humanity by His cross and resurrection. To the question, ‘why mission?’ we reply with the Church’s faith and experience that true liberation consists in opening oneself to the love of Christ. In Him, and only in Him, are we set free from all alienation and doubt, from slavery to the power of sin and death. Christ is truly our peace (Eph. 2:14); the love of Christ impels us (2 Cor. 5:14), giving meaning and joy to our life. Mission is an issue of faith, an accurate indicator of our faith in Christ and His love for us. The temptation today is to reduce Christianity to merely human wisdom, a pseudo-science of well-being. In our heavily secularized world a gradual secularization of salvation has taken place, so that people strive for the good of man, but man who is truncated, reduced to his merely horizontal dimension. We know, however, that Jesus came to bring integral salvation, one which embraces the whole person and all mankind, and opens up the wondrous prospect of divine filiation” (December 7, 1990, no. 11).

The day of happiness

Aware of the dangers he faced, Father de Britto bid farewell to the Christians and suggested they go into hiding, saying “What God is demanding me, He is not asking of you.” On January 8, he was arrested. When the soldiers approached, he turned himself over to them to allow the Christians around him to flee. A Brahmin who had become Christian and two catechists were taken with him. He was beaten and ordered to invoke Shiva, but instead he invoked Jesus. One night, a powerfully built catechist who had not been captured came to rescue him. Father de Britto refused, saying “Leave that to Providence!” The next day, he was taken on a journey of several days to Ramnad, where he found himself with six other Christians. Father de Britto had been able to keep his breviary; each day he drew from it an account of the life of a martyr for his companions. He also wrote to his French friends in Pondicherry and his Jesuit superiors asking them not to intervene on his behalf, knowing how precious the witness of his blood would be for the neophytes who were still subject to persecution. He was secretly sentenced to death on January 28, but fearing a widespread riot, the authorities announced that he would be exiled, for there were a great number of Christians in this area. Two days later, along with a few other Christians, he was moved to Oriyur, where he wrote his final letters. The governing prince there, who was sick, asked his prisoner to cure him in exchange for sparing his life. The missionary spoke to him of another cure, a moral and spiritual one, but the prince refused to understand and ordered his execution. Father de Britto wrote to his friend, Father John da Costa, a last letter full of faith, humility, and hope: “I have been taken to Oriyur to be beheaded there. I have greatly suffered on the journey, but I have finally arrived. Presented before the tribunal, I endured a long interrogation on the faith, which I defended. From there, I was returned to prison, where I now await the day of happiness. But to obtain it, I need your prayers. The joy of the Lord abounds in my heart and sustains my strength. I am surrounded by guards, I cannot tell you more. Farewell, my dear Father. Please convey this letter to all our Fathers. Your servant and friend in Jesus Christ, John de Britto.”

The new apostle of the Indies was beheaded on February 4, 1693, Ash Wednesday. The soldier who executed him, and whom Father de Britto had embraced beforehand, would convert and receive Baptism, along with great numbers from this land. Beatified on August 21, 1853 by Blessed Pius IX, John de Britto was canonized by Pius XII on June 22, 1947; his feast day is February 4. Oriyur has become a very popular pilgrimage site among the Christians of southern India.

Echoing the life of Saint John de Britto, Pope Francis reminds us today that “the more Jesus occupies the center of our lives, the more He allows us to come out of ourselves; He de-centers us and He brings us closer to others. This dynamic of love is like the movement of the heart… they concentrate to encounter the Lord and immediately open up, coming out of themselves for love, to bear witness to Jesus and speak of Jesus, to preach Jesus. He gives us the example Himself: He would retire to pray to the Father and then He would go immediately to meet those hungry and thirsty for God, to heal them and save them” (Message of July 5, 2017, to participants in the first international catechetical symposium, in Buenos Aires, July 11-14, 2017). Let us ask the Holy Spirit to make us true witnesses of Jesus Christ.