March 2, 2022

Blessed Eugene Bossilkov

Dear Friends,

A child was playing on the bank of the Danube, near the borders of Bulgaria and Romania. It is a river almost 3,000 km (1,770 mi) long; here, it is close to its mouth. Suddenly, the child slipped and tumbled into the water. The tumultuous waters carried him away, threatening to swallow him down; already his distraught mother had lost sight of him. Invoking Our Lady with an energy born of despair, she made a promise there and then: she would consecrate her son to the Blessed Virgin, if only She would save him! Within moments, the child emerged from the water, and succeeded in reaching the shore. His mother hugged him tight. She would not forget her promise: Vincent would belong to Jesus, through Mary.

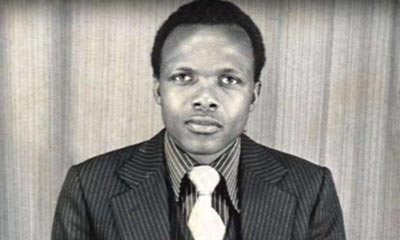

Vincent Bossilkov was born on November 16, 1900 in Belene, in northern Bulgaria. The population in this country is mainly Greek Orthodox, a denomination of Eastern Christians who do not recognize the authority of the Roman Pontiff. However, the Bossilkov family were part of the small Catholic minority made up of peasants of the Danube valley who had been evangelized by Venetian missionaries since the 16th century. Vincent’s parents, Louis and Beatrice, were farmers. A courageous and hard-working boy, Vincent was confirmed in 1909; before long, he told his parents of his desire to become a priest. His mother viewed this as a consequence of having offered up her child to Mary. Two years later, she took him to the minor seminary of the diocese of Nicopolis. This very ancient diocese had been revived by Pope Innocent X in 1644, after a centuries-long interruption. But in 1688, the Turks had almost destroyed it, with the massacre of fifteen of its twenty-five priests, while the others took refuge in Hungary. In 1782, Passionists (an order founded by St. Paul of the Cross, 1694-1775) returned to the villages that had remained Catholic. Although of Latin rite, they celebrated Mass according to the Eastern rite, which was more familiar to the population. Because the political authorities regarded them with suspicion (the country was still under the control of the Ottoman Empire), they exercised their apostolate with the utmost discretion. The priests celebrated Mass, often at night, in barns or in cellars especially dug out for this purpose, or in private houses. Being Catholic meant having to face general hostility. However, in 1878, Bulgaria became independent, and the “tsar”, Ferdinand, ins-tituted religious tolerance.

Vincent Bossilkov was born on November 16, 1900 in Belene, in northern Bulgaria. The population in this country is mainly Greek Orthodox, a denomination of Eastern Christians who do not recognize the authority of the Roman Pontiff. However, the Bossilkov family were part of the small Catholic minority made up of peasants of the Danube valley who had been evangelized by Venetian missionaries since the 16th century. Vincent’s parents, Louis and Beatrice, were farmers. A courageous and hard-working boy, Vincent was confirmed in 1909; before long, he told his parents of his desire to become a priest. His mother viewed this as a consequence of having offered up her child to Mary. Two years later, she took him to the minor seminary of the diocese of Nicopolis. This very ancient diocese had been revived by Pope Innocent X in 1644, after a centuries-long interruption. But in 1688, the Turks had almost destroyed it, with the massacre of fifteen of its twenty-five priests, while the others took refuge in Hungary. In 1782, Passionists (an order founded by St. Paul of the Cross, 1694-1775) returned to the villages that had remained Catholic. Although of Latin rite, they celebrated Mass according to the Eastern rite, which was more familiar to the population. Because the political authorities regarded them with suspicion (the country was still under the control of the Ottoman Empire), they exercised their apostolate with the utmost discretion. The priests celebrated Mass, often at night, in barns or in cellars especially dug out for this purpose, or in private houses. Being Catholic meant having to face general hostility. However, in 1878, Bulgaria became independent, and the “tsar”, Ferdinand, ins-tituted religious tolerance.

By the time Vincent en-tered the Passionist minor seminary at the age of eleven, ten successive Passionist bishops had headed the diocese of Nicopolis since 1804. It was there that he later entered the novitiate, where he took the name of Eugene of the Sacred Heart. He already knew the Passionist priests well, as they had been providing parish services in Belene for many years. Vincent Bossilkov outshone his comrades by his liveliness and his intellectual gifts, but also by his mischievous personality. Gradually his vocation became stronger. The bishop of Nicopolis, Damien Thelen (1877-1946), who lived in Ruse, the most important city in the north of Bulgaria, bore him great affection and often predicted that this child would one day be his successor. In 1914, Vincent was sent by his superiors to Belgium and then to Holland, to ensure that he would receive a better education. The young man would not see his country or his family for ten years, a sacrifice generously accepted by all. At the Passionist convent in Kortrijk, he was profoundly inspired by the example of a brother who was ill with cancer and who lived through his ordeal in a saintly way; the Church would later proclaim Brother Isidore De Loor (1881-1916) blessed. During the German occupation of Belgium, Brother Eugene took refuge in the Dutch convent of Mook where he completed his classical studies and showed great talent for languages. Two Dutch ladies, Johanna and Lamberta Roelofs, decided to support him: they welcomed him into their home during vacations and also financed his studies. Brother Eugene would always remain very fond of them.

He pronounced his religious vows on April 29, 1920: on that day he promised to “make the crucifix the center of his life”. In 1923, he began to study theology and, the following year, he returned to Bulgaria, to Ruse. He was ordained a priest in 1926. His superiors then sent him to Rome where he obtained a degree in theology; back in Bulgaria, he prepared a doctoral thesis in theology which he completed in Rome in 1932, on “the union of Bulgaria with the Roman Church in the first half of the thirteenth century”. The question of Christian unity had become paramount for him, and he now bore the division of Eastern Christians as a personal wound. At that time (1925-1935), the apostolic delegate of the Holy See in Bulgaria, Monsignor Angelo Roncalli, the future Pope John XXIII, worked to promote dialogue between Orthodox and Catholics. Eugene Bossilkov, too, welcomed with great charity the Orthodox who came to him, while clearly confessing that unity could not be achieved without communion with the Bishop of Rome. In 1938, he contributed to the conversion of the superior of an Orthodox monastery to Catholicism.

A call from the Holy Spirit

“‘Christ bestowed unity on his Church from the beginning. This unity, we believe, subsists in the Catholic Church as something she can never lose, and we hope that it will continue to increase until the end of time.’ Christ always gives his Church the gift of unity, but the Church must always pray and work to maintain, reinforce, and perfect the unity that Christ wills for her. This is why Jesus himself prayed at the hour of his Passion, and does not cease praying to his Father, for the unity of his disciples: That they may all be one. As you, Father, are in me and I am in you, may they also be one in us, so that the world may know that you have sent me (John 17:21). The desire to recover the unity of all Christians is a gift of Christ and a call of the Holy Spirit.” (CCC, no. 820). However, “Those ‘who believe in Christ and have been properly baptized are put in a certain, although imperfect, communion with the Catholic Church’. With the Orthodox Churches, this communion is so profound that it lacks little to attain the fullness that would permit a common celebration of the Lord’s Eucharist” (CCC, no. 838).

Eager for apostolic action, Father Bossilkov obtained from his bishop the care of the parish of Bardarski Gheran, in the Danubian plain. There he completed the construction of the church and built a large and modern parish center, organized various religious, cultural and sporting activities, and served as chaplain to the nuns. His area of preference was the pastoral care of young people, whom he worked hard to catechize before anything else. However, he wrote in 1938: “The religious situation in Bulgaria is not rosy. Freemasonry seeks to oppress Catholics. Foreign missionaries no longer have the right to preach. I am Bulgarian, so they cannot do anything against me; but they are keeping a close watch on me and are accusing me of having become westernized. I have not let myself be intimidated.”

In 1941, Germany occupied Bulgaria. Father Bossilkov was able to save many Jews threatened with deportation by the Nazis. At the end of 1944, the Soviets entered Bulgaria as conquerors. In 1946, Stalin established a “people’s republic”, i.e. a Communist dictatorship. On July 2, Father Eugene, now under the surveillance of the authorities, wrote in a pastoral letter: “Christ did not promise men paradise on earth; those who promise it—and they are in charge today in Bulgaria—will turn the earth into hell. I cannot keep silent and I speak out: that is why they summoned me twice to the police. But so far, the eel has slipped through their hands.” Bishop Damien Thelen, the bishop of Nicopolis, died on August 6th of the same year. A week later, the Holy See appointed Eugene Bossilkov apostolic administrator of the diocese, i.e. its temporary head as representative of the Pope. The situation was critical: the youth was being perverted by an atheistic and immoral education, and priests were being physically eliminated or discredited by slander campaigns. The administrator immediately set up an extraordinary popular mission to remind the faithful of the fundamental points of Catholic doctrine and to strengthen them so that they would resist the atheistic propaganda. His missionaries were not afraid to lead public debates against the party’s “doctrinarians”, and, thanks to their culture, the strength of their arguments and their faith, they easily gained the upper hand. Often the Communists would try to get away with insults and blasphemy when facing such opposition; for want of anything better, they would make their retreat shouting, “Dolu Bog!” (“Down with God!”).

The sure promise of a splendid future

On July 26, 1947, Pope Pius XII appointed Eugene Bossilkov as Bishop of Nicopolis. His chosen motto was “Justice and Charity”. Even the Orthodox were delighted with his appointment; he was the first Bulgarian bishop of Nicopolis since the 17th century. His diocese covered the northern half of Bulgaria, with 25,000 faithful, 31 priests, 123 nuns, 25 churches, three colleges and a seminary. He immediately began to visit them. In all the Catholic villages, he was enthusiastically welcomed and often carried in triumph by the faithful, who were proud of their bishop, a cultured prelate who spoke several languages, in whom their faith was embodied. He was said to be the best public speaker in Bulgaria. However, some priests, frightened by his apostolic daring, signified that they were not in the running for martyrdom. The bishop tried to encourage them: “With the Blessed Virgin, everything is possible.” In a pastoral letter of 1948, he confronted the atheist propaganda that was trying to ruin the rational basis of the Catholic faith (apologetics) in the minds of the people. In that same year, the government took measures designed to destroy the Roman Church in Bulgaria through the suppression of feast days and religious events outside churches, as well as the confiscation of ecclesiastical property. Catholic schools attended by six thousand young people were closed, as well as the hospitals, orphanages and dispensaries belonging to the Church. In 1949, foreign priests were forbidden, by decree, to have any ministry whatsoever in Bulgaria. When asked to countersign this decree, Bishop Bossilkov refused. He was well aware of the consequences: “The marks left by our spilt blood”, he said, “will be the sure promise of a splendid future for the Church in Bulgaria. The grain of wheat must die.”

Rising every day at 4:30 a.m., the bishop would pray until 8 a.m. before starting his work. “Prayer”, he said, “is the mother tongue of the soul. There are many things we are not able to do, but it is always possible to pray.” Speaking of small sacrifices, he said: “I sanctify my days by swallowing the many kinds of biscuits that the Lord gives me, be they sweet or bitter; they all come from a loving hand that makes everything sweet and flavorsome.” He phrased his daily resolution as follows: “I want to be good always, I want to bring joy and comfort to all.” To do this, he relied primarily on the daily celebration of Holy Mass, in which he offered himself to the heavenly Father in union with His divine Son, Priest and Victim. Like all members of the Passionists, Bishop Bossilkov had a special devotion to the Virgin of Sorrows. Known for his uprightness as a bishop, he earned the admiration and esteem even of his persecutors. A state official later declared that he had found himself in front of a man of extraordinary faith: “I have never heard anyone speak against Eugene, even among the leaders of the (Communist) Committee of Religious Affairs.”

Free in Christ

In 1948, Bishop Bossilkov was allowed to travel to Rome to meet with Pope Pius XII; he spoke with him at length. However, he was “escorted” by four Bulgarian policemen. He told those who advised him against returning to his diocese: “I am the shepherd of my flock; I cannot abandon it.” After praying for a long time before the icon of the Madonna in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, he confided to a fellow Passionist: “I asked for the grace of martyrdom.” In the West, the bishop rejoiced in breathing the air of freedom, but he also declared: “We in Bulgaria are free in Christ.” Back in Ruse, he said, “We are not afraid; as far as I am concerned, I have been preparing for the worst without hesitation.” Echoing a verse from Isaiah, he added: For Sion’s sake I will not hold my peace, and for the sake of Jerusalem, I will not rest (Is 62:1).

Stalin’s religious strategy in Eastern Europe consisted in founding national churches separated from Rome and headed by prelates who were subservient to the communist regime. Influential government figures promised Bishop Bossilkov many privileges if he would agree to become the head of a “national people’s church” detached from the Pope; the next step, predictably, would be the forced attachment of this schismatic church to the majority Orthodox Church in the country, which was controlled by the authorities. The bishop firmly refused and prescribed special prayers for the Pope in every parish.

Around that time (1946), in Croatia, Blessed Bishop Stepinac was invited by the Communist government to found a national church. His refusal earned him a heavy sentence. On October 7, 1998, four days after having beatified him, Pope John Paul II said of him: “His persecution and show trial resulted from his refusal to comply with the regime’s insistence that he break with the Pope and the Apostolic See and become head of a ‘national Croatian church’. He preferred to remain faithful to the Successor of Peter. For this reason he was slandered and then condemned.” “Particular Churches are fully Catholic through their communion with one of them: the Church of Rome, which presides in charity”, the Catechism teaches. “‘For with this church, by reason of its pre-eminence, the whole Church, that is the faithful everywhere, must necessarily be in accord’ (St. Irenaeus). Indeed, ‘from the incarnate Word’s descent to us, all Christian churches everywhere have held and hold the great Church that is here [at Rome] to be their only basis and foundation since, according to the Saviour’s promise, the gates of hell have never prevailed against her’ (St. Maximus the Confessor)” (CCC, no. 834).

Treated without mercy

In 1949, Bulgaria’s diplomatic relations with the Holy See were broken off. The Minister of the Interior threateningly declared: “We know all the opponents of the People’s Government and we will treat without mercy those who will hinder us. Then neither God nor their imperialist patrons will be able to help them.” On March 1st of that same year, the bishop of Nicopolis was able to gather his Passionist confreres and a large number of the faithful for a last time for a Triduum in Oresch, during which he spoke with complete apostolic liberty. Shortly afterwards, the last twelve foreign priests still in Bulgaria were forced to leave the country. The bishop instructed them to say, in Rome and everywhere else, that the Bulgarian Catholics would remain faithful to God and to the Church. Because the postal mail was being censored, Bishop Bossilkov began to use coded language. He wrote to his foreign correspondents: “You cannot imagine the hell we are going through here.” In 1952, when he was once again approached to become the head of a schismatic Church, he reaffirmed his loyalty to the Pope. On July 16, seven policemen broke into his home in his presence and searched for weapons and radio transmitters. Finding nothing, they used a postcard received from Holland to accuse the bishop of collusion with an enemy power, and arrested him. That same day, a massive police raid led to the incarceration of forty priests and several religious and lay people in a cold and sinister prison.

A public trial was opened on September 29. The friends and relatives of the accused who were able to slip into the court were terrified when they saw him enter, emaciated and unrecognizable: for two months he had been forced to sleep on the floor; food deprivation and torture were inflicted upon him every night in order to make him confess to imaginary crimes. Despite this terrible “brainwashing”, Bishop Bossilkov remained undaunted. An eyewitness recalled that he “dominated everyone with his answers and made his judges uncomfortable”. His family was allowed to see him for ten minutes; he took the opportunity to tell them: “I am ready to do anything to remain faithful to Christ. Pray that I may be worthy of the grace of martyrdom. Tell everyone that I have betrayed neither the Church nor the Pope.” On October 3, the sentence that had been agreed upon long before was proclaimed: the bishop of Nicopolis and three priests of the Assumptionist congregation were sentenced to death and to the confiscation of their property for “spying on behalf of the Vatican and subversive activities against the State”. Bishop Bossilkov received this devastating news with serenity; a smile appeared on his face. A Communist official present at the trial recalled: “We Bulgarians had asked Moscow not to sentence him to death, but Stalin had given precise orders and there was nothing that could be done.”

“I betrayed neither the Church nor the Pope!”

During a final conversation with his niece, Sister Gabrielle, and another nun, the bishop tried to console them: “I feel myself sustained by the grace of God. I willingly die for the faith. I regret that you should remain alone, but the Blessed Virgin will not abandon you. If I had wanted, I could have lived with all the amenities I could have wished. Tell everyone that I have betrayed neither the Church nor the Pope.” While awaiting execution, the condemned prisoners lived isolated from each other in tiny cells, bound by a chain from foot to neck. Every week, Bishop Bossilkov received a hamper of food sent by the nuns. When returned, the hamper always bore a “signature”: a tiny slip of paper marked “+Eug”. On November 18, the basket was returned full. Her heart sinking, Sister Gabrielle understood that the bishop had been executed. Thanks to the compassion of a policeman, she was able to recover the blood-stained clothes and personal belongings of the martyr. The officer informed her unofficially that the bishop was shot on November 11, 1952, at 11:30 p.m., along with the three other condemned priests. This information was later confirmed to Pope St. Paul VI, in 1975, during an interview with the Bulgarian communist leader, Zhivkov.

Eugene Bossilkov was proclaimed Blessed by Pope John Paul II on March 15, 1998, in Rome, in the presence of Sister Gabrielle. The bishop of Nicopolis had predicted “a splendid future” for the Bulgarian Catholic Church; this prophecy began to come true in 1989, the year of the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe. The Catholic Church emerged from the chaos and reconstituted its visible structures with two Latin dioceses (Sofia and Nicopolis), as well as an “eparchy” (diocese) for the Greek Catholics. In 2002, during a trip to Bulgaria, the Holy Father beatified the three other martyred priests: Fathers Kamen Vitcev, Pavel Djidjov and Josaphat Chichkov. Today, there are about 50,000 faithful in Bulgaria, together with their native clergy. Pope Francis visited Bulgaria in May 2019.

During the homily for the beatification of Bishop Eugene Bossilkov, St. John Paul II could say in all truth: “This Bishop and martyr, who throughout his life strove to be a faithful image of the Good Shepherd, became one in an altogether special way at the moment of death when he united his blood with that of the Lamb sacrificed for the world’s salvation. What a shining example for us all, called to bear faithful witness to Christ and his Gospel! What a great encouragement for those who today are still suffering injustice and oppression because of their faith! May the example of this martyr, whom we contemplate today in the glory of the blesseds, instill faith and zeal in all Christians!”