April 6, 2022

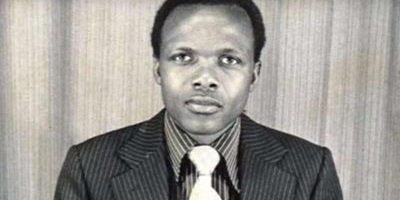

Blessed Benedict Daswa

Dear Friends,

In a country where freedom of religion is guaranteed by the State and where about 80 percent of the population call themselves Christians, can it be that a person is killed because of his or her faith in Jesus Christ? Yet, it is but a few years ago that in South Africa, Benedict Daswa, a devout Catholic, clashed, to the point of laying down his own life, with the mindset of his fellow citizens who believe that atmospheric disasters, illness and death are due not to natural causes, but to the presence of evil spirits manipulated by human beings. Benedict, the father of a large family, was beatified on September 13, 2015. “The Beatification of Benedict is a blessing for the whole Church, for South Africa, for the whole of Africa,” emphasized Cardinal Angelo Amato: his name, “Tshimangadzo means wonder, miracle, and he was an authentic wonder of God… The Holy Spirit had transformed this young South African into an authentic hero of the Gospel… He resembles the first martyrs of the Church who, at the time of the persecutions of the Roman emperors, defended their faith with prayer, courage and forgiveness of their enemies.”

Benedict Daswa was born on June 16, 1946, in the small village of Mbahe, in the Transvaal Province. The region had been evangelized at first by Protestant missionaries, and later by Catholics, mainly from Ireland. The child was identified in the register of births and deaths as follows: Tshimangadzo Samuel Daswa Bakali. Samuel was the Christian name required by the English administration, Daswa was the name of the family, and Bakali was the name of the Lemba tribe to which he belonged. His parents, Petrus and Ida, would go on to give birth to four more children. The family practiced the traditional animist religion, which ascribes a soul to all natural phenomena and practices ancestor worship, and even spiritism at times. The boy’s parents were farmers and stockbreeders, but his father also worked as a builder and woodcarver, to help supplement the meager income from the farm. “Our father showed us that we must work at home and work for ourselves. At the same time, he showed us that we must love one another and even love children that did not belong to our family,” one of his daughters later recalled. Benedict was an always respectful and obedient son. According to Mrs. Daswa, his father had a special love for their eldest son.

Benedict Daswa was born on June 16, 1946, in the small village of Mbahe, in the Transvaal Province. The region had been evangelized at first by Protestant missionaries, and later by Catholics, mainly from Ireland. The child was identified in the register of births and deaths as follows: Tshimangadzo Samuel Daswa Bakali. Samuel was the Christian name required by the English administration, Daswa was the name of the family, and Bakali was the name of the Lemba tribe to which he belonged. His parents, Petrus and Ida, would go on to give birth to four more children. The family practiced the traditional animist religion, which ascribes a soul to all natural phenomena and practices ancestor worship, and even spiritism at times. The boy’s parents were farmers and stockbreeders, but his father also worked as a builder and woodcarver, to help supplement the meager income from the farm. “Our father showed us that we must work at home and work for ourselves. At the same time, he showed us that we must love one another and even love children that did not belong to our family,” one of his daughters later recalled. Benedict was an always respectful and obedient son. According to Mrs. Daswa, his father had a special love for their eldest son.

Benedict’s mother was the heart of her home, both generous and loving. She helped in the fields, mastered the art of brewing beer and sold second-hand clothes to bring a little extra money into the household. After her conversion to Catholicism, following in the footsteps of her son, she showed great fervor in her faith; she was a humble, straightforward woman who was always eager to help those in difficulty. When her children complained that they did not have enough to eat, she would reply: “The little we have, we should share with those in need.” Benedict’s brother thus summed up the spirit of the family: “Welcome everybody, and if we did not have enough beds, we got out of our beds to sleep on the floor and give our beds to guests; that was a sign of our culture. If we did not have enough food, the food would go to the guests and we would eat the remains. The guests eat first in our culture.”

Outright refusal

Before he started school, Benedict herded the family’s flock; his father also taught him the basics of fruit and vegetable growing, providing him with a small plot of land next to the family vegetable garden. In 1957, the child began his schooling in a primary school. From 1962 to 1965, he studied at another school, run by the Salvation Army, and then completed his education at high school in 1968. After receiving specific training, he was awarded a teacher’s license in 1970. He was supported by his uncle, Frank Gundula, who worked in Johannesburg, during his school years. Thanks to a Catholic friend, the schoolboy became aware of the beauty and truth of the faith. A catechist who brought together a group of catechumens every Sunday under a fig tree taught him the beginnings of the faith. After two years of instruction, the young man was baptized on April 21, 1963 by Father Augustine O’Brien. He chose the name Benedict because of his great admiration for the life of the patriarch of the monks of the West, whose motto he adopted: “Ora et labora” (pray and work); three months later, on July 21, he received the Sacrament of Confirmation. Benedict then turned to Father Patrick (“Paddy”) O’Connor who became his spiritual guide. “He called to the mission for a job but, since I did not have any, I offered him the money to complete (his studies). He refused and said he would try Sibasa for a job,” Father O’Connor remembered. There he found work as a hospital cleaner. But one day, having asked Benedict what his religion was, his employer told him that if he wanted to keep his job he must leave the Catholic Church and join his own religion. Benedict refused outright. “I took him to the mission,” Father Patrick continued, and this time he accepted money: “I told him he could return it if he wished when he was working. He returned it and much more.”

Benedict’s fidelity to his Christian commitment, by the grace of the Holy Spirit, is an example of the kind of Christian heroism that St. John Paul II would later describe: there is “a consistent witness which all Christians must daily be ready to make, even at the cost of suffering and grave sacrifice. Indeed, faced with the many difficulties which fidelity to the moral order can demand, even in the most ordinary circumstances, the Christian is called, with the grace of God invoked in prayer, to a sometimes heroic commitment. In this he or she is sustained by the virtue of fortitude, whereby—as Gregory the Great teaches—one can actually ‘love the difficulties of this world for the sake of eternal rewards’” (Encyclical Veritatis Splendor, August 6, 1993, no. 93). “If any man will follow me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross, and follow me. For whosoever will save his life, shall lose it: and whosoever shall lose his life for my sake and the gospel, shall save it” (Mk 8:34-35).

Finding joy in work

Now a teacher, Benedict regarded his work as a true vocation: “He took up teaching,” his sister later explained, “because he liked children and wanted to teach them to become responsible people when they grew up.” At first he taught in a primary school. He obtained a higher qualification in 1973 after following a correspondence course. He taught his pupils good manners, respect for each other, for the law, for elders, but also for the truth. He was particularly sensitive to the plight of children from very poor backgrounds, and allowed them to work in his vegetable garden, paying them so that they could buy books and school uniforms, or even just continue their school education. He was convinced that children should be made used to work and not be dependent on free handouts, and would tell them: “If you do something without being pushed you will enjoy it.”

“Working persons, whatever their job may be, are cooperating with God himself, and in some way become creators of the world around us. The crisis of our time, which is economic, social, cultural and spiritual, can serve as a summons for all of us to rediscover the value, the importance and necessity of work for bringing about a new ‘normal’ from which no one is excluded. Saint Joseph’s work reminds us that God himself, in becoming man, did not disdain work,” writes Pope Francis (Apostolic Letter Patris Corde, December 8, 2020, no. 6).

Starting with a prayer

In his modest way, Benedict did not want his acts of generosity to become public knowledge: he quietly provided financial assistance to parents of children who were in real need of it. He regularly paid visits to families whose children no longer wanted to go to school. “Children are our light of tomorrow,” he said. “We have to do everything we can to make sure they get a good education.” As school principal of Nweli School in 1978, he built five more classrooms, introduced school uniforms and school meals, inaugurated a vegetable garden, and encouraged all kinds of sports, as well as music and singing classes both at school and in the village. He started a football team for the boys, but withdrew from it when some of the players wanted to use performance-enhancing drugs, and set up another team. He also refused to wear amulets that were supposed to ensure victory. In school, he was a demanding principal who expected faultless professional and moral conduct from both students and teachers. With the latter, he formed support groups where he and the other colleagues could be counted on for help when things got difficult. Benedict was particularly strict with regard to punctuality, especially on the part of the teachers: “If we want to maintain discipline with children, we ourselves must be found to be honest in our work and so we should not leave school early.” On one occasion, a teacher broke this rule: Benedict gave chase in his own car and caught up with him, and drove him straight back to school to ensure that the teacher would properly prepare for the next day’s lessons, before driving the culprit home, again in his own car. He became a member of the Transvaal Teachers’ Union and was elected secretary of the local branch. He always opened Union meetings with a prayer, even if he had to say it alone when no-one else was willing to join; he was not ashamed to conduct himself in public in accordance with the Faith. Although he did not make a show of it, or try to impose it on others, he did not hide it.

Benedict, as the eldest child, provided for his family through his work following the death of his father, thereby making it possible for several members of his family to obtain an education. His honesty and integrity earned him the respect of his own village community. In 1974, he married Shadi Eveline Monyai (she died in 2008) and the couple had eight children. In defiance of ancestral customs, he exposed himself to mockery by fetching water from the river, washing the children’s nappies, and helping his wife with the housework; he encouraged his sons to do the same. For him, the equal dignity of both spouses was not just a theory. “Men,” he said, “should not expect all kinds of services from their wives when they are already busy with family chores.” So unusual was his behavior that some people went so far as to claim that he was bewitched. He built a brick house for his family with his own hands. He had a very affectionate relationship with his children. His eldest child, then in secondary school, vividly remembered their last conversation before Benedict’s death: “He drove me to St. Brendan’s and we chatted for a long time. We prayed and then we hugged.” Benedict also extended the same care and concern to his cousins and nephews.

“Their own responsibility”

For Benedict Daswa, faith in Jesus Christ was the source upon which the life of the family was to be nourished so that it might become a true “domestic church” (cf. CCC, no. 1656). “He used to teach us how to say the Rosary, read the Bible and the Order of the Mass. He taught us to take part in Church youth activities. Every evening we used to have family prayer,” one of his daughters recalled. Benedict’s sister-in-law remembered: “What I saw of the relationship between the parents and their children was exemplary. They were trained not to eat before praying, and to pray after meals, to pray before they went to bed and when they woke up.” A catechist who had the privilege of being received into the Daswa home described what he saw: “Before going to bed, the family came together in prayer. He read the Bible, there was singing, then we recited the Act of Contrition, the Our Father, the Hail Mary, prayers known by heart and Prayers of the Faithful. Benedict and Eveline passed on the faith to their children as their responsibility. They didn’t just leave it to the Church or to the grandparents to do so.” On a broader scale, Benedict organized family gatherings for sharing and friendship. At Christmas, they all came together, and everyone would receive a small gift. They took turns having meals in each other’s homes.

“Parents are the principal and first educators of their children… It is in the bosom of the family that parents are by word and example, the first heralds of the faith with regard to their children. They should encourage them in the vocation which is proper to each child, fostering with special care any religious vocation” (CCC, nos. 1653 and 1656).

Benedict’s entire life, both public and private, was shaped by his relationship with Christ. Many were impressed to see the director helping his wife at home, or working in the garden like an ordinary laborer. When a colleague who had just been promoted to a management position came to him for advice, Benedict told him: “Let’s start with a prayer.” He opened his Bible, read a few verses and asked God to guide them through the meeting. Then he said: “A school principal must be humble. He must be humble with his staff. He must be humble with his learners. He must be humble with the parents.” “And do you all insinuate humility one to another,” Saint Peter told the early Christians (1 Pet 5:5).

Benedict was also very committed to his mission as a catechist. Sister Angela, coordinator of catechism courses in his parish, was deeply impressed by the holiness of his life: “I would go so far as to say that everything about him was Christ-like… He was a person who not so much talked about his faith as lived it deeply and quietly.” Benedict’s spiritual life was nourished by prayer and frequent reception of the sacraments. He sometimes conducted the Sunday meeting in the absence of a priest, and belonged to a Small Christian Community that met, sometimes at his home, to pray the rosary and share the Word of God. In his view, the spread of the Gospel depended on strong and lively parishes. When a parish council was set up, he was elected as its president, and urged those who could afford it, especially state-paid teachers, to contribute to the upkeep of priests and catechists. He helped build the church at Nweli, dedicated to the Assumption of Mary, patron saint of South Africa, sometimes even going so far as to transport stones and other building materials in his own vehicle. His influence led young people from the region to agree to participate in this work. Some blamed him for having given priority to the building of the church over the construction of his own house. He devoted his spare time to charitable activities: visiting the sick and the poor, but also Catholics who had abandoned their religious practice. Moreover, he did not limit his charity to Christians. When he was asked to assist in domestic quarrels, he would first gather his own family and ask them to pray for the struggling couple. In some serious cases, his daughter later testified, “he would tell us to fast before attempting to solve problems.” His influence often succeeded in restoring peace.

A dangerous rejection

Benedict showed a keen interest for social life and was indeed the secretary of the traditional village council. The local chief valued his insights and held him in high esteem. But Benedict’s way of life, never hiding his faith, earned him many enemies who condemned him for having abandoned animist traditions and embraced the Christian faith, which they identified with the Western mentality. His clear rejection of witchcraft earned him the enmity of several members of the village council; those jealous of his achievements attributed them to witchcraft, even his flourishing vegetable garden… In the years preceding Benedict’s death, there was a resurgence of superstition-related crimes, especially in the north-eastern region of South Africa.

“All practices of magic or sorcery, by which one attempts to tame occult powers, so as to place them at one’s service and have a supernatural power over others—even if this were for the sake of restoring their health—are gravely contrary to the virtue of religion. These practices are even more to be condemned when accompanied by the intention of harming someone, or when they have recourse to the intervention of demons. Wearing charms is also reprehensible. Spiritism often implies divination or magical practices; the Church for her part warns the faithful against it. Recourse to so-called traditional cures does not justify either the invocation of evil powers or the exploitation of another’s credulity,” the Catechism teaches (CCC, no. 2117).

Just a few cents

Between November 1989 and January 1990, several houses in Benedict’s village were hit by lightning and burnt down. The “wise men” claimed that this was not natural, and due to witchcraft. Some suggested that the Christian teacher was to blame. The village council decided to call in a well-known sorcerer to determine whether this was true, and each family head was asked to contribute to the payment of his fees. Benedict refused to pay the required sum of 5 rand, or less than 50 cents. He tried to explain to the chief and his advisors that lightning and storms are natural phenomena, and that the search for culprits would surely lead to the murder of innocent people. Because of his faith in Jesus he could not accept their decision, he proclaimed. This led to insinuations that his refusal was an indication that he was guilty. Fully aware that he was in danger, Benedict asked his friends to pray for him; on the Sunday preceding his assassination, he spent a particularly long time in church praying with his Bible. On January 25, 1990, an unusually violent storm hit several thatched huts. On the 28th, the chief convened a council where the matter of the lightning strikes was discussed before Benedict arrived. They agreed to collect the funds needed to consult the sorcerer. On being informed, the school principal again refused to contribute.

On February 2, feast of the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple, Benedict drove his sister-in-law to the doctor with her sick baby. On his way back, a young man carrying a heavy bag of vegetable produce asked him for a ride home. After Benedict had dropped him off, night was already falling. He headed towards his own village, but a tree trunk and large stones blocked his way. He got out of his car and was confronted with youths who threw stones at him. Wounded and bloodied, he tried to take refuge in a nearby house, but was forced to leave when his assailants threatened to set it on fire. In vain, he asked to be spared, but obtained a brief moment to pray. While he was kneeling, a young man struck him with a heavy club, breaking his head. Another man poured boiling water on him. So died this exemplary layman, at the age of forty-five.

During the beatification ceremony of Benedict Daswa at the church in Nweli, which he had helped to build, Bishop Rodrigues of the Diocese of Tzaneen commented: “Benedict lived in a spirit of freedom founded on the freedom of Jesus Christ. His faith in Christ freed him from the fear of witchcraft and evil spirits and everything related to these dark forces. Indeed, Blessed Benedict’s life and death testify that witchcraft and all forms of divination are useless and a meaningless burden which enslaves the human spirit by continually playing on our fears and ignorance.” In man, freedom is a force for growth and ripening in truth and goodness. The choice of disobedience and evil is an abuse of freedom and leads to the slavery of sin (cf. Rom 6:17). Freedom reaches its perfection when it is ordered to God, who is our beatitude. Jesus Christ came to show us the way to true freedom. It is important to bear witness to this through our faithfulness to the Gospel: “The fidelity of the baptized is a primordial condition for the proclamation of the Gospel and for the Church’s mission in the world. In order that the message of salvation can show the power of its truth and radiance before men, it must be authenticated by the witness of the life of Christians” (CCC, no. 2044). May Blessed Benedict Daswa obtain for us the grace to bear witness to Christ with our whole lives, so that in all things God may be glorified!