September 21, 2018

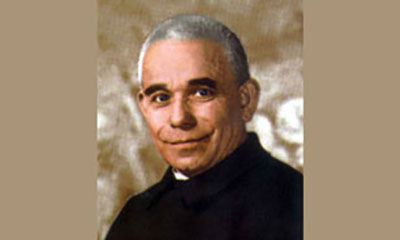

Mgr Buguet

Dear Friends,

The evening of November 1, 1876, Auguste Buguet is ringing the bells at the church of Our Lady of Mortagne-au-Perche, in Normandy. One of the bells breaks loose and, having gone through the vault, leaving its outline there like a hole-punch, falls on the bell ringer, crushing him. The day after this accident, the brother of the deceased, a priest, is deeply struck by the suddenness of this death, writing, “My God, permit me to meditate on Your goodness. Under the dreadful misfortune, I am crushed with sadness. Your goodness alone can sustain me.” Immediately afterwards, a cry bursts from his priestly heart: “And his soul?” Not knowing the spiritual state of his brother at the moment of the accident, he begs, “O my God, tell me that You love us… Tell me that you have saved my brother.” It is a distress most understandable for the human heart, but which ends in an act of abandonment to God: “Everything which happens, the smallest occurrence, the fall of a hair, does not happen without the permission or the will of God, and God cannot want or permit anything unless it is for our good. From this, I conclude that I can leave myself completely at God’s disposal.”

Father Buguet’s attitude came from his faith in the last article of the Creed: “I believe in life everlasting.” The importance of this article escapes no one, for it expresses the term and the goal of God’s plan for humanity. But, in our day, many people, even Christians, feel a certain malaise and anxiety about this topic. Is there anything after death? Doesn’t nothingness wait for us after death?

To shed light on this most important question, the Church affirms the survival of a spiritual element after death called the “soul,” which is gifted with conscience and will, such that the human self lives on. Indeed, the human person, created in the image of God, is a being at once corporal and spiritual. The Bible expresses this reality when it maintains that the Lord God formed man out of the dust of the ground and He blew into his nostrils the breath of life, and so man became a living being (Gen 2:7). This breath of life refers to the deepest part of man, his spiritual “soul,” which renders him most particularly in the “image of God.” Each human soul is directly created by God; it is not “produced” by the parents. Separated from the body at death, it is reunited with it again at the Final Resurrection (cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church, 362-363; 366).

Thanks to his soul, man can reflect on the world in order to understand it, and he can perceive that which is not material (love, goodness, beauty, justice, etc.) “Man is not deceived when he regards himself as superior to bodily things… For by his power to know himself in the depths of his being he rises above the whole universe of mere objects… So when he recognizes in himself a spiritual and immortal soul, he is not being led astray by false imaginings that are due to merely physical or social causes. On the contrary, he grasps what is profoundly true in this matter” (Vatican II, Gaudium et spes, 14).

Eternal destiny

What happens then to the soul after death? “In fidelity to the New Testament and tradition, the Church believes in the happiness of the just who will one day be with Christ. She believes that there will be eternal punishment for the sinner, who will be deprived of the sight of God, and that this punishment will have a repercussion on the whole being of the sinner. She believes in the possibility of a purification for the elect before they see God, a purification altogether different from the punishment of the damned. This is what the Church means when speaking of Hell and Purgatory” (Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Letter of May 17, 1979).

This teaching on the faith shows the seriousness of the problem of the soul’s salvation, for the destiny of man after death is irrevocable and eternal. This is why our Lord could say, “What does it profit a man, if he gain the whole world, but suffer the loss of his own soul?” (Mt 16:26). From this, one can understand Father Buguet’s concern for the eternal destiny of his brother. In the hope of salvation he prayed for him, so as to obtain his entrance into paradise. Then, extending his thought to all the deceased, the priest considered this death as an invitation from Heaven to commit himself to a work of mercy for the dead. He had, however, to work for many years before his plan would be realized.

Who was Father Buguet? Paul-Joseph Buguet was born on March 25, 1843, in Bellavilliers, Orne, France. His impoverished parents barely supported themselves and their two sons. Serious classical studies in a school in Mortagne prepared Paul for his entry into the seminary in Sees in 1862. There, he devoted himself with great care to his studies “for God, the Church, and for souls.” “There are three things to which I must tend: mortification, humility, and cultivation of the inner spirit. With that, I will succeed in becoming a holy priest.” He was ordained on May 26, 1866.

After twelve years of ministry as vicar at Sainte-Honorine-la-Chardonne, then as a parish priest at Saires-la-Verrerie, Father Buguet arrived, the 1st of August 1878, at the 700-member parish of La Chapelle-Montligeon, where he had just been appointed parish priest. The area was poor; departure for the city threatened the region. Crushed by the competition of new factories, the old cottage weaving industries were closing. The young people went to the cities, where their faith was put to a difficult test. “Distressed by this need which showed me the parish would be deserted in the future,” the priest said, “I spent long moments at the foot of the statue of Saint Joseph, begging him to inspire me with a way of giving the people work and bread without requiring them to go seek their living in the cities.”

To this end, he attempted a jersey manufacture, on behalf of a large Parisian producer—it failed. Then lace making—another failure. Then glove making—after an initial success, the invention of glove making machines, which the poor people of La Chapelle-Montligeon were not able to afford, brought about the abandon of this handicraft.

Father Buguet, who did not forget his desire to come to the aid of the deceased, found himself thus pressed by two interests: “I was trying,” he said, “to reconcile this double goal: to have prayers said for the abandoned souls of Purgatory, to free them from their pains by the Sacrifice of the Mass, which contains the supreme expiation, and in return, to obtain thereby the means to support the worker. This was in my mind as a reciprocal gift between the suffering souls of Purgatory and the poor abandoned ones on earth. It was a mutual deliverance.” This double goal would be reached in an entirely providential manner.

The Monday Mass

For a long time, Father Buguet had felt himself commanded by an interior voice to establish a charity for the deliverance of the abandoned souls of Purgatory. Offering the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass one day in the oratory dedicated to Saint Joseph, Patron of a Good Death, he received a “mission” in regard to this intention. An extraordinary occurrence would launch the charity.

“I loved to celebrate the Mass on Mondays for the most abandoned soul of Purgatory, and I felt that these souls obtained many favors for me,” the priest explained. “In May 1884, a person I did not know came to me to ask me to celebrate a Mass for her intentions. Her face indicated that she was about fifty years old; she was dressed very modestly, wearing the clothing of a poor woman of the people; her air inspired respect and confidence. Eight days later, at this Mass that I was celebrating at her request, I was surprised to see her at the back of the church, dressed in a sky blue dress and her head covered by a long white veil, which came just to her waist. Who was she? I have never known… She prayed for a long time before the altar of the Blessed Virgin.” Many people would see this woman, who came twice. When she left for the second time, a dozen people followed her with their eyes. She disappeared suddenly. Those are the facts.

Father Buguet confided to his closest friends: the mysterious lady had praised him and thanked him “for this charity that he had to say the Mass each Monday for the most abandoned soul in Purgatory.” From the time of this “visit,” he felt driven to draw up the rules of “The Work of Expiation.”

A few pennies!

Starting September 3, 1884, he took the necessary steps to organize this charity. He first had to obtain the authorization of the bishop to establish an association so as to have Masses celebrated for the benefit of the most abandoned soul in Purgatory. The dues asked of members of the association amounted to a sou (a few pennies) a year. “My good Father, what will you do with a sou?” the bishop asked him. “Your Grace, it will be the charity of the poor.” “Well, do as you wish. If you do not succeed, you will be to blame; and if God wills it, nothing will stop your work.”

Father Buguet consequently made himself “the traveling salesman of the Souls of Purgatory.” He traveled through the region, from parish to parish. A sou, no one would refuse that. He complemented his visits with a little bulletin, which flew more quickly and farther than he. At the end of three years, all the dioceses of France knew the charity. It also extended to foreign countries: England, the Netherlands, Italy, Spain, Canada, then the Antilles, China, Japan, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Palestine, Russia, Syria… Before the end of the century, Father Buguet, his traveling stick in hand, would cross Europe as well as a part of the United States and Canada.

This apostolate necessitated the printing of a bulletin intended to make known the spiritual initiative of Montligeon. The beginnings were very modest, but one thing led to another, and second-hand printing machines were bought, workers learned the trade, orders came from outside. Little by little, an admirably equipped factory was created. Father Buguet thus providentially realized his desire of obtaining work for his parishioners.

A misunderstood dogma

One of the first bulletins printed by the work noted the little care generally taken for the eternal repose of the deceased. “You are not unaware, dear readers, of how little the people of the world are concerned with the deceased. When the son and the daughter have shed a few tears on the remains of their parents, when they have laid a few wreaths on the grave, and—in good families—when they have asked for some Masses to be said for the repose of their souls, they think they have fulfilled their obligation towards them.”

Even today, the dogma of the purification of sins in Purgatory is often misunderstood. The Catechism of the Catholic Church thus explains this truth of the faith: “All who die in God’s grace and friendship, but still imperfectly purified, are indeed assured of their eternal salvation; but after death they undergo purification, so as to achieve the holiness necessary to enter the joy of Heaven… The tradition of the Church, by reference to certain texts of Scripture (cf. I Cor 3:15; I Peter 1:7), speaks of a cleansing fire” (CCC, 1030-1031). This final purification of the elect is very different from the state of the damned in Hell; for the latter are forever excluded from Paradise and do not know love. The souls of Purgatory love God, and are sure to go to Heaven at the end of their expiation.

“Sin has a double consequence,” explains the Catechism. “Grave sin deprives us of communion with God and therefore makes us incapable of eternal life, the privation of which is called the `eternal punishment’ of sin. On the other hand every sin, even venial, entails an unhealthy attachment to creatures, which must be purified either here on earth, or after death in the state called Purgatory. This purification frees one from what is called the ‘temporal punishment’ of sin. These two punishments must not be conceived of as a kind of vengeance inflicted by God from without, but as following from the very nature of sin” (CCC, 1472).

Supreme mercy

Purgatory is the supreme mercy that God reserves for those who have died in love, but who have not gone through the ultimate demands of love. They would now see God face to face, but they are not able to. “The suffering which results from it is purifying. It is a kind of exile, a suffering in love and from love, but purely expiating and satisfying” (Cardinal Journet [1891-1975], Forgiveness of Sin-Indulgences, 1966-67).

The fire of Purgatory acts as an instrument of Divine Justice and, in an inexpressible way, it touches the soul “to the quick.” Souls which endure it withstand at each instant all the weight and all the depth of a sorrow which they cannot distract themselves from. The Fathers of the Church teach that the sufferings of Purgatory surpass the most severe that one could imagine on earth. Yet these souls are not without consolations. The greatest consists of the certitude of being loved by God and of being unable to lose Him by sin. In addition, the love which torments the souls of Purgatory mysteriously fills them with a profound joy, and hope gives them a very gentle patience.

Beautiful mysteries

The souls of Purgatory can do nothing to alleviate their pains. But “so that they might be relieved of them, the sufferings of the living faithful are useful to them, that is, the offering of Masses, alms, and other works of piety which are performed by the faithful for other faithful” (Council of Florence). “This teaching is also based on the practice of prayer for the dead, already mentioned in Sacred Scripture: ‘Therefore (Judas Maccabeus) made atonement for the dead, that they might be delivered from their sins’ (2 Mac 12:46). From the beginning the Church has honored the memory of the dead and offered prayers in suffrage for them, above all the Eucharistic sacrifice, so that, thus purified, they may attain the beatific vision of God. The Church also commends almsgiving, indulgences, and works of penance undertaken on behalf of the dead: ‘Let us help and commemorate them. If Job’s sons were purified by the their father’s sacrifice (cf. Jb 1:5), why would we doubt that our offerings for the dead bring them some consolation? Let us not hesitate to help those who have died and to offer our prayers for them’ (Saint John Chrysostom)” (CCC, 1032). “We touch on beautiful mysteries,” wrote Cardinal Journet. “Great charity (practiced on earth) being able to purify all the punishment of our sins, Purgatory could be avoided; in this sense it is abnormal, and this explains why the Church of Purgatory, reduced under this aspect to powerlessness, depends entirely upon the charity of the Church on earth.” There exists then between the faithful of Purgatory and those who are still on earth “a perennial link of charity and an abundant exchange of all good things” (Paul VI, cf. CCC, 1475).

Thus the views of Father Buguet are explained, who wrote, “My God, give me the grace to penetrate well this thought: Expiation. Ah! If I understood well all the gentleness that is in this word, I would not have the fear of mortification that I do. I would love penance, and it would be a consolation for me… Well! To diminish Purgatory, do penance. For that, one can offer everything, from dawn to dusk, all one’s afflictions, sorrows, worries…“ And he devoted himself with courage to “the Work of Expiation.” The side chapel of the little old church of Montligeon became its headquarters. Pilgrims came in ever greater numbers to pray at the foot of Our Lady of Deliverance. Six years after the start of this apostolate, Father Buguet, who had been joined by many collaborating priests, envisioned a construction whose majesty would crown it.

A basilica in the country

One day in the summer of 1894, the founder of the Work presented himself to his bishop: “Your Grace, I would like to undertake the building of a great church for the most abandoned souls of Purgatory.” “How much have you collected already?” “Not quite 50,000 gold francs.” “Well, my dear Father, when you have 100,000 francs, you will begin.”

The priest returned disconcerted to Montligeon. He found there a letter from a lady in Paris, inviting him to come to see her for a gift which she wanted to make to him. The gift was precisely 50,000 francs! The surprised bishop gave the authorization to begin the work of construction. To solicit new gifts, the founder created The Quarterly of the Church of Our Lady of Montligeon. The result was and remains extraordinary—a vast basilica in the open field. Its design is in the shape of a Latin cross 74 meters long. Two spires frame the facade. Inside, above the main altar, is placed a statue of the Virgin Mary, carrying the Child Jesus, which she offers to a soul, represented as a human form at the point of entering paradise. Another soul represents the firm expectation of Heaven. The whole was sculpted from a block of marble from Carrare; it measures 3.7 meters tall and weighs 13 tons. Everything draws the viewer to admiration, to prayers for the living and the deceased, to a living and firm hope of Heaven.

The sight of this church is unforgettable. But this building is nothing more than an edifice for facilitating pilgrimages and soliciting the prayers which are the principal and heavenly end of the Work of Expiation. Like all the works of God, this did not fail to undergo contradictions. Anticlerical newspapers often attacked Father Buguet. He was accused of being mercenary, because of the large sums of money he handled for his construction work and for the celebration of Masses. The priest had the wisdom and grace, however, to not be affected by these malicious or libelous insinuations.

Conversely, he received from Pope Leo XIII and Pope Saint Pius X well-merited ecclesiastical honors, with the title of “Monsignor.” His humility was not damaged—he kept his rank in the church with simplicity. His tone remained familiar, even jovial. “Everything is done by the prayer of the humble man,” he used to say. “God blesses the plans of the man who prays and humbles himself.” And when he was asked how he was able to realize his work, he contented himself to reply, “I pray, and it’s the good Lord who does the rest.” Monsignor Buguet expired peacefully in Rome, June 14, 1918.

The fire of love

The example of Monsignor Buguet urges us to intercede for the souls in Purgatory. In 1998 the Church celebrated the one thousandth anniversary of the feast of All Souls, November 2, instituted by Saint Odilon, Abbot of Cluny, and spiritual son of Saint Benedict. “For the souls of Purgatory,” wrote Pope John Paul II on the occasion of this anniversary, “the hope of eternal happiness, of meeting the Beloved, is a source of suffering because of the pain of sin which keeps the individual far from God. But there is also the certitude that, the time of purification completed, the soul will go to meet Him whom it desires… I therefore encourage Catholics to pray with fervor for the deceased, for those in their families and for all our brothers and sisters who have died, so that they might obtain the remission of the punishments due their sins… Confident in the intercession of Our Lady, of Saint Odilon and of Saint Joseph, Patron of a holy death, I wholeheartedly grant the faithful who will pray for the dead my apostolic blessing.”

May we too live in great love of God so as to purify ourselves entirely of our faults here below, according to the words of Saint Thérèse of the Child Jesus and of the Holy Face: “I know that of myself I do not merit even to enter into the place of expiation, since the holy souls alone can have access there, but I know as well that the Fire of Love is more sanctifying than that of Purgatory” (Ms A 84°v).

Let us ask the Holy Spirit to light in us the Fire of His Love and to renew the face of the earth.