December 3, 2020

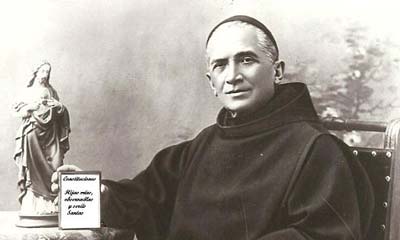

Father Giacomo da Balduina

Dear Friends,

“The confessor is called daily to the ‘peripheries of evil and of sin,’ and his work represents an authentic pastoral priority,” said Pope Francis on March 17, 2017. “Hearing confessions is a pastoral priority. Please, let there be no such signs as: ‘Confessions heard only on Mondays and Wednesdays from a certain time to a certain time.’ Hear confession every time you are asked. And if you are there [in the confessional] praying, keep the confessional open, as God’s heart is open.” Father Giacomo da Balduina fulfilled his mission as a confessor in a spirit of deep faith.

Beniamino Angelo was the eighth of ten children born to Giacomo Filon and Guiseppina Marin. He was born on August 2, 1900, near Padua, Veneto, in northern Italy. His father amply provided for the family by managing the extensive agricultural lands belonging to Baron Ugo Treves. Guiseppina was the soul of the family at their home in Balduina. Under her pious and dedicated guidance, Beniamino enjoyed a peaceful childhood in the lively environment of his family. He was always eager to help others and readily gave way to the desires of his brothers and sisters. As a boy, he was captivated by the religious ceremonies the family attended at the nearby parish church. He admired the priests and soon learned to serve Mass. At home, he organized a small parish made up of local children. He said his “Mass” on an altar made by his older brother, Francesco; his mother’s aprons served as liturgical vestments. Lacking a pulpit, he delivered his sermons standing on a chair. He held solemn funerals to lay dead animals to rest. He even went so far as to “wed” some of his playmates, with all seriousness and gravity. For Beniamino, these childish games were the natural continuation of his inner life, that expressed itself in the seclusion of personal prayer and the assiduity of his service to the priest at the altar. At the age of ten, he received the sacrament of Confirmation; his First Holy Communion took place the following year.

Beniamino Angelo was the eighth of ten children born to Giacomo Filon and Guiseppina Marin. He was born on August 2, 1900, near Padua, Veneto, in northern Italy. His father amply provided for the family by managing the extensive agricultural lands belonging to Baron Ugo Treves. Guiseppina was the soul of the family at their home in Balduina. Under her pious and dedicated guidance, Beniamino enjoyed a peaceful childhood in the lively environment of his family. He was always eager to help others and readily gave way to the desires of his brothers and sisters. As a boy, he was captivated by the religious ceremonies the family attended at the nearby parish church. He admired the priests and soon learned to serve Mass. At home, he organized a small parish made up of local children. He said his “Mass” on an altar made by his older brother, Francesco; his mother’s aprons served as liturgical vestments. Lacking a pulpit, he delivered his sermons standing on a chair. He held solemn funerals to lay dead animals to rest. He even went so far as to “wed” some of his playmates, with all seriousness and gravity. For Beniamino, these childish games were the natural continuation of his inner life, that expressed itself in the seclusion of personal prayer and the assiduity of his service to the priest at the altar. At the age of ten, he received the sacrament of Confirmation; his First Holy Communion took place the following year.

The Count of Padua

Meanwhile, young Beniamino struggled at school. He had difficulty learning his lessons and his marks were poor. During his three years of elementary school in Balduina, the only things his teacher could praise were his punctuality, his spirit of discipline and his positive attitude. For the next four years, he attended a school in Lendinaria, in the neighboring province of Rovigo. His reserved and solitary nature soon made him the target of local hoodlums, especially since Paduans were seen as rivals. Beniamino used to ride to school on his bicycle, a rare luxury. One day, he was attacked by two jealous fools: “There goes the Count of Padua; let us bow to him and throw a stone at him.” The peaceable child was hit on the head, but he forgave his companions. More than once, he returned home injured. In Lendinaria, he discovered a Capuchin convent. Everything there appealed to him. He fell under the charm of the friendliness of the Friars and their smiling welcome; and of their habits, girded by a cord with three knots, and the office they sang in the chapel. From the outset, he made himself fully at home in the convent. His parents often offered hospitality to the mendicant Friars on their travels, and many disciples of the “Poverello,” Saint Francis of Assisi, shared meals with the family. It was through his proximity with these barefoot Friars, with their untrimmed beards and their simple and joyful poverty that the child heard the call of God.

His parents rejoiced when he revealed to them his desire to answer that call. But their parish was torn by quarrels, which delayed the young man’s entry into the minor seminary several times. Finally, Father Carlo Trentin, a priest of strong character, took Beniamino under his wing and recommended him to the Capuchin Fathers: “My young parishioner has always been irreproachable. He is humble, modest, obedient, attends church assiduously, and loves religious ceremonies. He serves Mass with truly impressive reverence. He is an attentive teacher to the children who come to catechism classes. He receives Holy Communion every day: he has never had any other desire than to fulfil his familial and religious duties to the best of his ability. This is why I can confidently say that he has always been the most edifying example of what a pious, modest, true Christian son should be.” Beniamino entered the Seraphic college (the minor seminary that trains future Capuchins) in Rovigo on October 13, 1917. He was seventeen years old, while the other students were all ten or eleven. But he fit in well and willingly submitted to school discipline. A former classmate, Father Albert de Dueville, described him with these words: “Reserved, very shy, perhaps even a little melancholy, with somewhat limited abilities. He was of normal height but his constitution was frail; he was rather sickly. His pale, anemic face always radiated a sweet gentleness. He spoke little, but when he did, his conversation was always calm, simple, brief, but full of wisdom… On the rare occasions when he received a rebuke, he remained calm and dignified.”

Not made for religious life

In March 1918, Beniamino was drafted into the army. He was assigned to the 68th infantry regiment in Milan, where he was quick to share his rations with his comrades; he never complained. When on leave, he would go to the nearest parish to offer his services. He struck people as a pious, peaceful, patient, and smiling young man. After he was discharged in 1921, he rapidly resumed his studies at the minor seminary. On September 28, 1922, he adopted the brown Capuchin habit in Bassano del Grappa, where he was given the name of Friar Giacomo of Balduina. During his year of novitiate, he familiarized himself with convent life, the daily liturgical office and housework. One day, the Master of Novices bluntly told him: “Dear son, you are not made for the religious life. You are not doing well in your studies, you are too shy to beg.” Friar Giacomo insisted: “If truly, I cannot become a religious, please be patient and charitable with me; I will do the dishes, I will sleep in the stable if there is no room for me in the convent.” His reply satisfied the Father, and Friar Giacomo took his temporary vows on September 29, 1923. On that occasion, he heard the following words of praise spoken to his mother: “Dear Madam, I must admit that your son is quite perplexing, for he doesn’t know how to do anything but pray.”

As a young professed Friar, he then embarked on three more years of study. During this period, a fellow student praised a brotherhood called the “Pious Union of Victim Souls.” Friar Giacomo replied that he had nothing left to give: he had already offered himself up as a victim for priests, and pronounced the heroic act of charity for the souls in Purgatory: “Dear God, in union with the merits of Jesus Christ, your Son, and the most Blessed Virgin Mary, I offer to you for the sake of the poor souls all the satisfactory value of my works during life, as well as all that will be done for me after death.” On December 8, 1926, the young Capuchin made his solemn profession before the Provincial Vicar. He then embarked on three years of theological studies in Venice. To the surprise of his superiors, his work was quite satisfactory. However, in 1927-1928, his health suddenly declined and he experienced alarming symptoms. He could only walk slowly, in small hurried steps, as if he were going to fall forward. Although he was generally in full possession of his intellectual faculties, he expressed himself with difficulty. In hot weather, he was tongue-tied; he could neither remember nor reason. He also had intestinal problems and insomnia. As a result, he would remain alone in his cell for hours.

Peaceful joy

In May 1928, a doctor diagnosed him with Parkinson’s disease, which worsened continually. He still attended some classes, and Father Paolino of Premariacco gave him private lessons, summarizing and explaining the other courses. His superiors in the Province of Venice wondered whether it would be appropriate to ordain him. However, following the advice of Father Paolino, Brother Giacomo was dispensed from one year of study. As his illness was not yet too advanced, he received minor orders, the sub-diaconate, and the diaconate. On July 21, 1929, he finally received the priesthood from the hands of the venerable Pietro La Fontaine, Patriarch of Venice. On August 4, he sang his first Mass in his parish of Balduina. Father Carlo Trentin proudly welcomed him and gave a vibrant speech for the occasion. Father Giacomo, now a priest for all eternity, radiated peaceful joy. Every year, he would offer thanksgiving for the beautiful day of his ordination, which he always viewed as a gift from Heaven. He continued to study theology in Venice for another year, to the extent of his abilities.

He was then sent to Slovenia for fifteen months, and after that to Udine in Friuli. The Capuchin convent there was a haven that welcomed those who wanted to be reconciled with God and discretely begin a new life. Father Giacomo dedicated his life to the ministry of confession. A cell was arranged for him with a grille in the wall, allowing him to hear penitents without having to move. For sixteen years, he received dozens of people there every day. At all hours, in front of an image of Christ crowned with thorns, he welcomed all those who came, as if to a dispensary of God’s forgiveness.

The power to forgive sins, which Christ gave to his Apostles on the very evening of his Resurrection (cf. Jn 20:23) as the first fruit of his Passion and death, applies to the greatest evil that can affect us. As the Catechism of the Catholic Church reminds us, “To the eyes of faith no evil is graver than sin and nothing has worse consequences for sinners themselves, for the Church, and for the whole world” (CCC, No. 1488). However, St. John Paul II said, “the specific ministry of priests does not exclude, but rather includes the ‘common priesthood’ of the faithful. ‘He who created us without our help will not save us without our consent,’ said St. Augustine. The active role of the Christian in the Sacrament of Penance consists in acknowledging one’s own faults through confession which, save in exceptional cases, is made individually before the priest; in expressing repentance for the offense to God, that is, contrition; in humbly submitting to the institutional priesthood of the Church to receive the “efficient sign” of divine forgiveness, absolution; to offer the satisfaction imposed by the priest as a sign of personal participation in the reparatory sacrifice of Christ who gave himself to the Father as a Host for our faults; and thanksgiving for the forgiveness obtained” (General Audience on 15 April 1992, No. 7).

“My joy remains unchanged”

Father Giacomo became the ordinary confessor of two-thirds of the clergy of Udine. He was always available and offered great comfort to his penitents, even interrupting his meal or his afternoon sleep, despite suffering from a persistent inflammation of the brain. The Auxiliary Bishop of Udine, Bishop Luigi Cicuttini, later wrote: “For years I was a penitent of the revered Father Giacomo. He always welcomed me with the heart of a father, and I always felt comforted when I left. He spoke little, but his smiling face, his paternal kindness were such that they impressed heavenly comfort upon the heart.” Yet Father Giacomo experienced some failures in his ministry, but these very disappointments grounded him more deeply in faith, hope, and charity, as expressed in a prayer he left us: “Dear Lord, the creatures I have loved out of love for you may have forsaken me, but my joy remains unchanged, because you alone, Lord, will not forsake me. And I hope, with your grace, never to forsake you.”

“Receive the Holy Spirit. For those whose sins you forgive, they are forgiven; for those whose sins you retain, they are retained” (Jn 20:22-23). With these words, Jesus established his Apostles as true judges of the inner dispositions of those who seek forgiveness for their sins. This is a great burden for a man who is himself a sinner! How can priests acquit themselves of this task if they do not maintain an intimate relationship with the One who gave his life to save sinners? “The ‘good confessor,’” says Pope Francis, “is, first and foremost, a true friend of Jesus the Good Shepherd. Without this friendship, it will be quite difficult for that paternity to mature, the paternity so necessary in the ministry of Reconciliation. Being friends of Jesus means first of all cultivating prayer: be it personal prayer with the Lord, asking ceaselessly for the gift of pastoral charity, or a specific prayer for the exercise of the task of confessors and for the faithful, the brothers and sisters who approach us in search of God’s mercy. A minister of Reconciliation who is ‘wrapped in prayer’ will be the credible reflection of God’s mercy and will prevent the harshness and misunderstandings that, at times, can be generated even in the sacramental encounter. A confessor who prays clearly knows that he himself is the first to sin and the first to be forgiven. One cannot forgive in the Sacrament without the awareness of having been forgiven first. Therefore, prayer is the first guarantee to avoid any attitude of harshness, which pointlessly judges the sinner and not the sin. In prayer it is necessary to ask for the gift of a wounded heart, capable of understanding the wounds of another and of healing them with the oil of mercy, that which the Good Samaritan poured on the wounds of the unfortunate man, on whom no one had taken pity (cf. Lk 10:24). In prayer, we must ask for the precious gift of humility, so it may always clearly emerge that forgiveness is a free and supernatural gift of God, of which we are always simple, albeit necessary, administrators, through the very will of Jesus. And he will surely be pleased if we make broad use of his mercy. In prayer, then, let us always invoke the Holy Spirit, who is the Spirit of discernment and compassion” (March 17, 2017).

Safety close to the Tabernacle

One day, Father Giacomo was sent to consult an eminent professor of neuropathology in Udine. The doctor’s diagnosis was incontrovertible: “I note that this Father has post-encephalitic Parkinsonism. The disease will worsen progressively, and with fatal consequences, and the patient will be unable to fight it within a few years.” Father Giacomo was treated with scopolamine, a substance that delays the progression of the disease and diminishes its symptoms. In 1934, his superior wrote: “The Bulgarian treatment has had a truly miraculous effect on Father Giacomo, who now walks straight, speaks easily, and no longer trembles. His right leg does still drag a bit… This treatment will take long: we have written to Bulgaria to obtain the medication.” But World War II broke out, and scopolamine became almost impossible to obtain. Permission was asked for Father Giacomo always to celebrate the votive Mass of the Blessed Virgin seated in his room. The air-raid alerts terrified him. When the sirens wailed and everyone went to the shelters, he would take refuge in the chapel close to the tabernacle, where he felt safe and could regain his calm.

Father Giacomo offered up his difficulties in silence, even when the pain was intense: “I am fine,” he would often repeat. Indeed, his face was usually serene, relaxed, and calm. But a letter to his sister Cesira in 1938 discreetly revealed another side of him: “I have so much I could tell you… for the time being it’s best that I keep quiet and pray, so that the Lord may accomplish through us all that is good for us, and give us the strength to endure, with Christian resignation, the ordeals of this poor life.” “Bear everything for the love of Jesus” became his motto. A priest later revealed that when he fell ill as a seminarian, Father Giacomo said to him, “I, on the other hand, cannot hope to improve. I offered myself as a victim to God for the sanctification of priests. God accepted my offering and made lethargic encephalitis the best way for me to accomplish my ideal.” Yet Father Giacomo did not radiate sadness. Not liking to see worried faces around him, he did not hesitate to brighten anxious brows by sharing cakes or opening a bottle that generous penitents had brought him and which he kept with the superior’s permission. He nevertheless maintained a spirit of mortification: despite his dispensation, he continued bravely to recite the liturgical office. And although he was exempt from the Eucharistic fast, which took effect from midnight at the time, prior to his Mass he took only the Belladonna tea prescribed to him.

“Guess where?”

In 1941, he shared with his sister Cesira a grace he had received when praying for his deceased parents. “I thought of them so much that my soul ardently longed for the day when it could be reunited with our dear parents in the paradise where they are waiting for us, and I heard a voice say, ‘Take heart, your exile will soon end, because the day when you can be reunited with your dear parents in paradise is not very far away.’ Forgive me, dear sister, if my words sadden you, but it is the pure truth.” And he did his best to comfort her. He felt freer to broach the subject within his community. As one Friar said, “He spoke quite often about his impending death with authentic joy. He gave the impression that he knew something about it: ‘I will die soon,’ he would say. ‘Guess where I will die?’ We asked him if he was joking. ‘I’m not joking at all… I will die soon, close to Our Lady, my mother.’”

One day in 1948, he asked his superior for permission to go to Lourdes. When he was told that such a trip was impossible due to his poor health, he humbly argued that the priests of the city wanted him to accompany them, and could easily assist him. He too wanted to go to the Blessed Virgin, even if it cost him his life. Permission was finally granted, and glowing with joy, he told his provincial, “I am going to Lourdes, but I will not return.” On July 20, he boarded the special train, and the next day, after 35 hours of travel, he reached his destination. His fatigue, however, prevented him from going directly to the baths. He asked to be accompanied in his recitation of the rosary. His condition quickly worsened, and at 11 p.m., after reciting the Magnificat, he gave up his soul to God. It was the nineteenth anniversary of his ordination; he was forty-eight years old. On July 23, he was buried in the cemetery of Lourdes. Ever since, many faithful come to visit his grave and decorate it with fresh flowers, even in winter. Graces are granted, and many ex-votos give witness to them.

His beatification process began on December 2, 1977. Father Bernardino of Siena, General Postulator of the Capuchins, wrote to the Archbishop of Udine: “Father Giacomo’s activities during his short forty-eight-year lifespan, twenty-six of which were spent in the convent, were limited: as a sick person, to suffering; and as a priest, to granting forgiveness in the Sacrament of Reconciliation. In the first activity, he showed how a Christian, with help from on high, can face both physical and emotional suffering without complaint, and even with a smile, while offering himself to God as a victim for the sanctification of priests. And in the ministry of confession, which he exercised with the same endurance and benevolence as his contemporary, St. Leopold Mandi´c, he showed how this hidden ministry can enhance the life of a priest and uphold his brothers in grace and goodness. He was, especially for the priests of the diocese of Udine, what St. Leopold Mandi´c was for the diocese of Padua: a manifestation of the merciful goodness of God.”

In Lourdes, the Virgin without sin is ever more welcoming to sinners. The guiltiest of souls seek out the purifying contact of the one who called herself the “Immaculate Conception.” An unfailing instinct tells them that she will know how to understand them, love them, console them, and renew their heart and spirit. With Father Giacomo of Balduina, and at the invitation of Our Lady of Lourdes, “Let us pray and do penance for the conversion of sinners.”