July 16, 2020

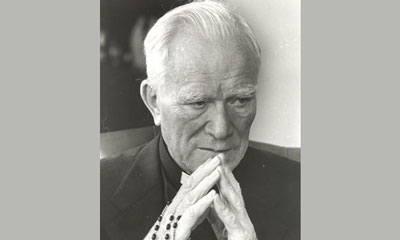

Don Francesco da Cruz

Dear Friends,

On June 3, 2016, the Feast of the Sacred Heart—a day specially dedicated to priests during the Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy—Pope Francis declared, “The great riches of the Heart of Jesus are two: the Father and ourselves. His days were divided between prayer to the Father and encountering people… So too the heart of Christ’s priests knows only two directions: the Lord and his people. The heart of the priest is a heart pierced by the love of the Lord. For this reason, he no longer looks to himself, or should look to himself, but is instead turned towards God and his brothers and sisters. It is no longer ‘a fluttering heart,’ allured by momentary whims, shunning disagreements and seeking petty satisfactions. Rather, it is a heart rooted firmly in the Lord, warmed by the Holy Spirit, open and available to our brothers and sisters.” There have been countless priests who lived exemplary lives throughout the Church’s history. One of these was God’s servant Francisco da Cruz, who edified Portugal through a life entirely devoted to God and human souls.

Francisco da Cruz was born on July 29, 1859, in Alcochete, near Lisbon (Portugal). His father ran a prosperous lumber business, and owned lands farmed by sharecroppers. His mother took care of the family, which already included Mary of Piety, Emmanuel, and Joseph when Francisco was born. Anthony and Isabel soon followed. The da Cruz family was deeply religious, and at the age of nine, Francisco unsurprisingly told his parents he wanted to become a priest. However, anticlerical sentiment reigned in Portugal at that time. The sirens of science, which were supposed to bring prosperity and happiness to the world with no thought of God, were charming humanity. In October 1875, Francisco began theology studies at the University of Coimbra. Though he was a serious student, his piety was limited to the minimum required by the Church: Sunday Mass, and yearly Confession and Communion. His desire to become a priest did not prevent him from enjoying life’s pleasures: he loved hunting, games, good food, and good cigars. He sang marvelously and attracted the attention of young women. He avoided near occasions of grave sin, but did not consistently resist bad thoughts, as he would later admit. Worried about him, his mother tried to hold him fast in the grip of her rosaries.

Francisco da Cruz was born on July 29, 1859, in Alcochete, near Lisbon (Portugal). His father ran a prosperous lumber business, and owned lands farmed by sharecroppers. His mother took care of the family, which already included Mary of Piety, Emmanuel, and Joseph when Francisco was born. Anthony and Isabel soon followed. The da Cruz family was deeply religious, and at the age of nine, Francisco unsurprisingly told his parents he wanted to become a priest. However, anticlerical sentiment reigned in Portugal at that time. The sirens of science, which were supposed to bring prosperity and happiness to the world with no thought of God, were charming humanity. In October 1875, Francisco began theology studies at the University of Coimbra. Though he was a serious student, his piety was limited to the minimum required by the Church: Sunday Mass, and yearly Confession and Communion. His desire to become a priest did not prevent him from enjoying life’s pleasures: he loved hunting, games, good food, and good cigars. He sang marvelously and attracted the attention of young women. He avoided near occasions of grave sin, but did not consistently resist bad thoughts, as he would later admit. Worried about him, his mother tried to hold him fast in the grip of her rosaries.

During family vacations, Francisco, for practice, would shoot sparrows in the courtyard with his rifle. One time, he failed to notice his young cousin lying in the grass under a bush. A bullet hit the child, blinding him in one eye. Sick with grief, Francisco decided to pay for the child’s education in reparation. Around the same time, he met Father Joseph Pires Antunes, a priest eleven years his elder. Francisco admired the older priest’s piety, but it took a grave illness before he began to follow his example. Finally understanding the precariousness of life and of sensory pleasures, Francisco grew closer to Christ, who alone never disappoints. Father Joseph spoke often with him about souls needing to be saved, and one day confided his decision to join the Jesuits and follow in the footsteps of Saint John de Britto, a Portuguese Jesuit missionary martyred in India in the 17th century. While waiting to enter, he prepared Francisco for his general confession and convinced him to join a Marian congregation. From then on, Francisco clearly belonged to Jesus through Mary, and abandoned his worldly life.

Attracting sympathy

Don Joseph was soon named professor at the seminary in Santarém. After obtaining his degree in theology, Francisco became a philosophy professor at the same seminary. Despite the headaches that had tormented him since his final exams, he accepted the appointment as Providence. On December 19, 1880, the young professor received minor orders. On August 15, 1881, his mother died from anthrax. With a fervor renewed and ripened by this trial, Francisco received priestly ordination on June 3, 1882. Lively and eloquent, others were attracted to him. His patience, gentleness, and goodness were greatly appreciated. But his long-standing struggle with his own temperament exhausted him and aggravated his headaches. At the beginning of the 1886 school year, he had to admit that he was unable to teach. It was the unravelling of all his hopes, despite so much effort. He was then named director of a school for poor orphans who were bound for the seminary, in the city of Braga. There everyone respected and admired him for his humble and calm authority. He never hit the children. When a child misbehaved, he had him kneel while he said himself the rosary. The children were rarely slow to respond to the Hail Mary’s. The great joy of the best students was to serve his Mass, and many sought to accompany him while he said his rosary in the park. The “good and saintly” Father Cruz, as he was called, taught French and Latin classes, and devoted a lot of money to rewarding his students’ efforts. But he soon found it difficult to celebrate Mass. In 1894, his body, once again exhausted, forced him to resign.

An immense task

After six months of rest in his hometown of Alcochete, Father Cruz went back to work. In October 1895, he was named spiritual director of the students in a minor seminary near Lisbon, which soon moved into the city. He devoted his free time to helping the poor and sick there: from the seminary overlooking the Tagus River he would walk down into the town and visit the slums. Powerless to single-handedly alleviate all the misery he found, he sought out the generosity of neighbors. He brought the hope of the Gospel to prisoners; even if everyone else rejected them, Jesus loved them as he had loved the good thief. Father Cruz’ reputation soon spread throughout the city, and his confessional was besieged by the faithful. Father Cruz’ duties as chaplain of the seminary, initially light, grew immense, and he gave himself to them without counting the cost, to the point that he ended up contracting pleurisy in 1899. He was forced to return to Alcochete once again to recover. His sister Isabel’s tenderness, along with the care of his brother Emmanuel, a doctor, slowly put him back on his feet. During his long recovery, he learned to accept his fragility, and determined to follow his Good Master without regret or restriction.

As Pope Benedict XVI said, “Being united to Christ calls for renunciation. It means not wanting to impose our own way and our own will, not desiring to become someone else, but abandoning ourselves to him, however and wherever he wants to use us. As Saint Paul said: ‘It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me’ (Gal 2:20). In the words ‘I do’, spoken at our priestly ordination, we made this fundamental renunciation of our desire to be independent, ‘self-made.’ But day by day, this great ‘yes’ has to be lived out in the many little ‘yeses’ and small sacrifices. This ‘yes’ made up of tiny steps which together make up the great ‘yes’, can be lived out without bitterness and self-pity only if Christ is truly the center of our lives” (Holy Thursday, April 9, 2009).

Anticlerical passions

In 1900, Father Cruz resumed his role of chaplain, but unable to keep up with all of his commitments, he resigned again in 1902. On February 2, 1908, King Carlos I and the Crown Prince were assassinated in Lisbon. Prince Emmanuel became king, but two years later had to flee to England following a military coup d’état. A Republic was declared, and anticlerical passions were immediately unleashed. Jesuits were blamed as the root cause of all problems. Starting in October 1910, monasteries were shut down and their assets seized. Separation of Church and State was instituted. Many Jesuits were imprisoned, others exiled. The persecution included forbidding the wearing of clerical clothes in public. Father Cruz moved to Lisbon, and, dressed in civilian clothes, visited imprisoned Jesuits. One night, in a presbytery in which he had taken refuge with other priests, he was surrounded by a group of armed soldiers. Rioters approached crying out, “Die!” The priests, who had done nothing wrong, bolted themselves inside, and the oak door held fast. The men of God confessed to each other. Father Cruz was unafraid, and comforted the others. At dawn, the soldiers left, but the rioters remained. Father Cruz stepped out, looked at the men with kindness, and proceeded to the church, greeting them as passed. The rioters responded softly, and dispersed as the priest rang the bell for the first Mass.

Don Francisco da Cruz visited the prisoners in Limoeiro. He was permitted to bring them provisions, but not to speak to them. For breaking this rule, he was himself once imprisoned for eight days. Afterwards, he went to see the Minister of Justice, Alphonse Costa, and obtained a safe conduct to visit the prisoners. Nevertheless, approaching the prisoners remained difficult, since many were not Catholic and cursed him. But his kindness, perseverance, and tact eventually softened their hearts. The Father gave all he had. He never refused a favor, helped with appeals and pardons, and found lawyers. He often appealed to the Minister of Justice. One day, someone said to him, “By intervening on behalf of such people, Your Reverence, you risk damaging your reputation.” “My reputation,” he replied, “is the only thing I possess. If it can help save someone, I offer it happily.” One day, he defended a prisoner who was going to be severely punished for attempting to attack him; moved to tears in the face of such goodness, the prisoner asked him to hear his confession. In four years, the Father had become the unfailing friend of the prisoners; he was expected, welcomed. One day, in a common area, he noticed that his wallet had disappeared. Addressing the group, he said, “We are all going to face the wall, you on one side, me on the other. I’m putting a bench between us and whoever found my wallet please place it on the bench.” The Father left with his wallet and all of its contents. Often, former prisoners would greet him in the street. He would be escorted through unsafe neighborhoods, “just in case.” Three hundred former prisoners attended his funeral.

“Look, a Jesuit!”

Father Cruz also extended his compassion to poor street children. No longer having to conceal his cassock, he was surrounded one day by a gang of excited children who cried out the worst insult they knew—“Look, a Jesuit, a Jesuit!”—before running off. He called them back by offering to buy them some bread. “I love being called a Jesuit,” he admitted to these children, whose hunger conquered their fear. In 1915, the Patriarch of Lisbon founded an association to strengthen the priestly spirit, and named Father Cruz as director. He led monthly meetings, urging his fellow priests to “Work, work continually! Look at Satan—he rests neither night nor day! Our mission is to hear confessions and preach as long as we have a flock of faithful, and to pray until we can pay no more!” He led by example.

The priestly ministry is essential to the Church, as Pope Benedict XVI recalled: “As Church and as priests, we proclaim Jesus of Nazareth Lord and Christ, Crucified and Risen, Sovereign of time and of history, in the glad certainty that this truth coincides with the deepest expectations of the human heart. In the mystery of the Incarnation of the Word, that is, of the fact that God became man like us, lies both the content and the method of Christian proclamation. The true dynamic center of the mission is here: in Jesus Christ, precisely. The centrality of Christ brings with it the correct appreciation of the ministerial priesthood, without which there would be neither the Eucharist, nor even the mission nor the Church herself. In this regard it is necessary to be alert to ensure that the ‘new structures’ or pastoral organizations are not designed for a time when we might ‘do without’ ordained ministry (the ministry of deacons, priests, and bishops), on the basis of an erroneous interpretation of the proper promotion of the laity” (Address to the Plenary Assembly of the Congregation for the Clergy, March 16, 2009).

In 1917, Sidónio Pais came to power. Though he was a Freemason, he nonetheless sought to reconcile the people and the Church, to put an end to arbitrary arrests, and to bring order back to the country. That same year, at Cova d’Iria in Fatima, three children who said they had seen the Blessed Virgin were waiting beside a well. They had a rendezvous with a priest they were told could read hearts; it would be in vain to try to lie to him, and their interest lay in being truthful from the start. “All the better if he reads hearts,” little Jacinta said to her cousin Lúcia. “He will then see that we are telling the truth.” Two churchmen slowly approached them, and an old priest mounted on a donkey got off and, his face lit up with a gentle smile, asked them, “Dear children, would you please lead me to the location of the apparitions?” It was Father Cruz. Hope sprang up in the young seers. Arriving at the foot of the holm oak, the priest slowly prayed his rosary, then reassured the children, “Have no fear, it is not the demon that you saw, as you have been told, but the Blessed Virgin!” Lúcia and Francisco relaxed, and Jacinta joyfully cried out, “You are a sweet old man!” The Father, who was only fifty-eight, laughed heartily. From then on, Jacinta always thought of him as “the Father who reads hearts.” After this encounter, Father Cruz often mingled with Fatima’s pilgrims. When asked if he had seen the sun dance, he responded, “No, I did not. I was not there on the day of the miracle, but I have seen so many tears dancing in the eyes of so many repentant sinners thanks to the miracle of Fatima, that it matters little to me!”

Mood swings

Filled with radiant joy, the Father did everything he could for others. However, he still sometimes had mood swings, and his bad temper sometimes led him to say hurtful words. As soon as he would realize what he had done, he would ask pardon. Despite his precarious health (he had pneumonia in 1927, 1945, and 1947) and persistent mental fatigue, Father Cruz continued his non-stop activity. He drew his energy from constant prayer, and crisscrossed the country in service to religious and prisoners, and seeking out sinners, particularly the most hardened. One day, on mission, he led a true Stations of the Cross in a railway car. Some of the travelers joined in the prayers. During another trip, he was reciting his rosary when two women asked him if he was not tired of praying all the time. He responded, “And you, Ladies, are you not tired of chattering all the time?” Once, during an illness, he called for a doctor. After an hour, the doctor came out of the room, overcome with emotion: “I came here to give an injection, and just made my first confession!” Father Mateo Crowley-Boevey, the tireless apostle of the Sacred Heart, wrote: “After having traveled the world, I can assert without hesitation that among many excellent priests, I have never met one as conformed to our adorable Model, another Christ as perfect as dear Father Cruz.”

Pope Francis said, “Let us ask ourselves what mercy means for a priest, allow me to say for us priests. For us, for all of us! Priests are moved to compassion before the sheep, like Jesus, when he saw the people harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd. Jesus has the ‘bowels’ of God, Isaiah speaks about it often: he is full of tenderness for the people, especially for those who are excluded, that is, for sinners, for the sick who no one takes care of… Thus, in the image of the Good Shepherd, the priest is a man of mercy and compassion, close to his people and a servant to all. This is a pastoral criterion I would like to emphasize strongly: closeness. Closeness and service, but closeness, nearness!” (Address to the Parish Priests of the Diocese of Rome, March 6, 2019).

“I have given all!”

Father Cruz gave freely, not keeping anything for himself. At the end of a Triduum, organizers realized that they mistakenly paid him the musicians’ fees, ten times higher than his own. He was asked to correct the situation. “Alas, it cannot be corrected. I’ve already given it all to the poor!” Another time, a barber who had just cut his hair saw him rooting through his black bag in which stole, surplice, holy water, needles, thread, paper, pencils, provisions and money were jumbled together. “My dear brother, I’m afraid that I have given everything away today, and have nothing left to pay you. The Good Lord will repay you.” The hairdresser was doubtful, but did not protest. The next day, he went to the parish and told the pastor. “I will pay you,” he said, “I know Father Cruz.” “No, no. Tell him that he is always welcome. Scarcely had he left when customers came pouring in. I have never earned so much money!” On his way to preach in Bragance, the Father got on the train without a ticket. En route, he explained to the conductor that he didn’t have any money but had to get there. The agent was unmoved and made him get off at the next stop. There, the Father remained at the platform, but the train did also: an inexplicable breakdown was announced. No one was able to identify the problem, so the conductor approached the mechanic: “I kicked Father Cruz off the train because he didn’t have a ticket, perhaps I shouldn’t have?” The Father got back on, and the train immediately departed!

In 1925, during a pilgrimage to Rome, Father Cruz asked Father Ledochowski, General of the Jesuits, to admit him into the Society of Jesus, but he refused to accept a sixty-six-year-old novice in poor health. Four years later, nonetheless, the Father General obtained from Pius XI permission rarely granted: Father Cruz could take his vows at the end of his life. In 1940, at the age of eighty-one, he asked for and obtained from Pope Pius XII, the grace to take his vows without delay, fearing he might die suddenly, without a chance to say them: it was his last great consolation. Bit by bit his strength faded. His nurse recounted, “Everyone was convinced that he was a saint. I felt in me something indescribable I never felt with other patients. I always tried to see Christ in them, but around him, so humble and so simple, so consumed with God, I also felt in my depths a great desire to love the Lord.” Father Cruz died on October 1, 1948, the first Friday of the month of the Rosary. He was buried on the feast day of St. Theresa of the Child Jesus, whom he loved deeply. Cardinal Cerejeira wrote, “Holy Father Cruz will remain one of the purest glories of our patriarchate. The clergy of Lisbon will always venerate him as a perfect example of apostolic ministry, of a priest entirely devoted to the glory of God and the salvation of souls. They will have in him a model and an advocate.” The cause for the beatification for Father Francisco da Cruz was opened on March 10, 1951.

“The priest is a gift of the Heart of Christ: a gift for the Church and for the world,” said Pope Benedict XVI (Angelus of June 13, 2010). “From the Heart of the Son of God, brimming with love, flow all the goods of the Church. In particular, originates in it the vocation of those men who, won over by the Lord Jesus, leave all things to devote themselves without reserve to the service of the Christian people, after the example of the Good Shepherd. The priest is molded by the charity of Christ himself, that love which impelled him to lay down his life for his friends and also to forgive his enemies. For this reason all priests are first and foremost workers of the civilization of love.”

Let us ask Father Francisco de Cruz to obtain from God many and holy priests for us.