March 19, 2021

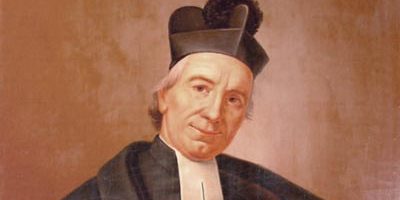

Saint Joseph-Benedict Cottolengo

Dear Friends,

Everybody in Turin (northern Italy) knows “The Little House of Divine Providence,” and calls it by the name of its founder: “The Cottolengo.” It houses over four hundred disabled people. Adjoining the home for the disabled stands a hospital with 203 beds. More than six hundred nuns devote themselves to caring for the sick. A total of twelve hundred volunteers from the Benedetto Cottolengo Organization work with the institute, which gives shelter to some two thousand people in Turin and elsewhere. According to Pope Francis, “This Little House’s raison d’être is not welfarism, or philanthropy, but the Gospel: the Gospel of the love of Christ is the strength that brought it into being and which makes it go forward: the love of Jesus’ predilection for the frailest and weakest. This is at the center. And for this reason, a work such as this does not go forward without prayer, which is the first and most important work of the Little House, as your Founder was fond of repeating, and as is demonstrated by the convents of the Sisters of Contemplative Life who are connected to the same Work” (June 21, 2015).

Joseph Benedict Cottolengo was born on May 3, 1786, in Bra, a large town south of Turin. He was the eldest child in a modest middle-class family. His father was a tax collector. His mother was very pious and attended Mass every day. She went on to bear eleven more children, six of whom died in infancy. Two of them followed their elder brother’s example and consecrated themselves to the Lord. Joseph Benedict soon stood out for his generous heart and wise judgment, but also for his spirited character. Under the direction of the parish priest of Bra, he gradually overcame his tendency to get carried away and lose his temper. At school however, lessons just would not enter into his head: “You understand everything right away, and I don’t understand a thing,” he complained to his classmates. Joseph Benedict did not seek to be educated to obtain a good position in life, but to become a saint. His mother suggested that he invoke St. Thomas Aquinas. His prayer was answered: he slowly climbed to the top of the class. He soon showed a keen awareness of the presence of God, writing in his notebooks, “God sees me.” He would often repeat, “In Domino!” (always to be and to act in God). His devotion to the Virgin Mary was awakened early on; he would often invite the members of his family to pray the rosary with him. His mother taught him to be caring for the poor, and would entrust him with giving them money, food, and clothing. As a teenager, he became a master in the art of begging for the poor he called his “own” from relatives, friends, and acquaintances. Combining asceticism with charity, he would often put his dessert or his afternoon snack in his pocket to give away. When he reached the age of seventeen, he sought to determine which path he should follow, as yet unsure whether he was called to the religious life or the secular clergy. He prayed often and earnestly to discover God’s will.

Joseph Benedict Cottolengo was born on May 3, 1786, in Bra, a large town south of Turin. He was the eldest child in a modest middle-class family. His father was a tax collector. His mother was very pious and attended Mass every day. She went on to bear eleven more children, six of whom died in infancy. Two of them followed their elder brother’s example and consecrated themselves to the Lord. Joseph Benedict soon stood out for his generous heart and wise judgment, but also for his spirited character. Under the direction of the parish priest of Bra, he gradually overcame his tendency to get carried away and lose his temper. At school however, lessons just would not enter into his head: “You understand everything right away, and I don’t understand a thing,” he complained to his classmates. Joseph Benedict did not seek to be educated to obtain a good position in life, but to become a saint. His mother suggested that he invoke St. Thomas Aquinas. His prayer was answered: he slowly climbed to the top of the class. He soon showed a keen awareness of the presence of God, writing in his notebooks, “God sees me.” He would often repeat, “In Domino!” (always to be and to act in God). His devotion to the Virgin Mary was awakened early on; he would often invite the members of his family to pray the rosary with him. His mother taught him to be caring for the poor, and would entrust him with giving them money, food, and clothing. As a teenager, he became a master in the art of begging for the poor he called his “own” from relatives, friends, and acquaintances. Combining asceticism with charity, he would often put his dessert or his afternoon snack in his pocket to give away. When he reached the age of seventeen, he sought to determine which path he should follow, as yet unsure whether he was called to the religious life or the secular clergy. He prayed often and earnestly to discover God’s will.

In 1802, Napoleon Bonaparte’s armies took over the Piedmont and closed the University of Turin. This gave Joseph Benedict the opportunity to receive classes from two Professors of the Faculty of Theology who had taken refuge in Bra. In 1805, he entered the seminary in Asti since his birth-town was affiliated with that diocese. He soon became known there for his piety, his good conduct, and his natural eloquence. He was nicknamed “Cicero.” He was ordained a priest at the age of twenty-five, on June 8, 1811; back in Bra, he lost no time in putting his zeal for the poor and for sinners in action, before being appointed a vicar in Corneliano. In 1814, after the fall of Napoleon, the University of Turin reopened its doors and the young priest continued his theological studies there. In 1818, his excellent defence of his doctoral thesis attracted the attention of the Canons of the Most Holy Trinity, who offered to receive him into their society. This congregation of six priests in Turin served the church called Corpus Domini, which was built in the 15th century to commemorate a Eucharistic miracle that had occurred there. It was an honour that Cottolengo had not sought after; besides, he had not been born in Turin—a requirement of the congregation’s statutes. However, an exception was made. The new canon was known for his obligingness to be of service to all. He found all kinds of ways to alleviate the work of his brothers, particularly through his regular presence in the confessional and his zeal in visiting the poor and sick. But he saw his time there as merely temporary.

“Grace has been granted!”

In September of 1827, a young couple, the Ferrario’s, were traveling from Milan with their three young children and made a stopover in Turin before going on to Lyons. The young woman, who was six months pregnant, suddenly experienced a serious malaise. The local hospital refused to admit her because of her advanced pregnancy. The maternity hospital would not admit her either, since she was not ready to give birth. Frightened and distraught, her husband could find only one refuge for his agonizing wife, the depot at the police station. It seemed pointless to give her treatment; a priest must be called. The priest who was found happened to be Don Cottolengo. With a heavy heart, crushed at the sight of the family’s despair, he prepared the young mother for death. How could the great city of Turin, the capital of a kingdom at the time, allow a sick woman to die like that, he wondered. Having carried out his painful duty, he went to kneel before the Blessed Sacrament: “My God, why? Why did you want me to witness this? What do you want from me? Something has to be done!” He rose, rang all the bells, and lit all the candles in the church. Welcoming curious onlookers into the church, he exclaimed, “Grace has been granted!” Don Cottolengo had just been transformed by the conviction that all his abilities, particularly his managerial and organizational skills, would be placed at the service of those most in need.

He presented his brothers with his plan to establish a modest dwelling with a few beds for foreigners who could not be admitted to public hospitals. When they agreed, the canons did not realize that they had just launched a great work. As it gained in importance, they did all they could to help their brother as much as possible. The beginnings were most humble, with charity as the only source of income. In January of 1828, Cottolengo rented two rooms in the house of the Red Vault. Soon after, other rooms were added as the number of patients increased. He received help from volunteers such as Dr. Granetti, who gave free treatment; the pharmacist Anglesio, who donated medicine; “ladies of charity,” served as nurses. But these pious people were unable to carry out all the tasks a hospital requires. With the help of a young widow, Marianna Nasi, Cottolengo created a society inspired by the “Daughters of Charity” who would receive a rule and be called the Vincentian Sisters.

The work was met with a great deal of goodwill, but its founder also faced a lot of criticism. Cottolengo was accused of having embarked on projects that were obviously beyond his means. Those around him, his family, and his brothers were worried and told him to give up his foolish plans. Creditors made claims and threatened him. At the archdiocese, the poor canon was accused of grabbing fortunes under the pretense of helping the poor. But the biggest ordeal was the cholera outbreak in Piedmont in 1831. Local house owners and neighbors became worried, and had the small hospital shut down. Don Cottolengo, fully abandoned to God’s will, considered the ordeal as no more than a call to rebuild a bigger place elsewhere. In the meantime, he took in abandoned little girls in the empty premises and set up a school. He soon found a small house for rent in the disreputable suburb of Valdocco in the Northern part of Turin, and dedicated it to the Blessed Virgin on April 27, 1832. Thus began the Little House of Divine Providence, which has since then ever retained its humble name of Piccola Casa. As its founder explained, “I chose this name because compared to the entire world, which is a house of the divine Providence, it is surely a very little house… and because it is not the work of man, but a work of divine Providence, which alone commands, guides, and directs.” Over its entrance are inscribed these words of St. Paul, which served as Don Cottolengo’s motto: “Caritas Christi urget nos—For the charity of Christ presseth us” (2 Cor. 5:14).

Immediate assistance

Cottolengo would often say: “I am a good-for-nothing… But surely, Divine Providence knows what it wants. All I need to do is to follow it. Onward, in Domino!” The Little House depended entirely on the charity of its benefactors. When asked where the money needed for his hospital came from, Father Cottolengo always replied: “Providence sends me everything.” Many stories illustrate this. A creditor who had failed to obtain a sum he was owed was starting to leave, uttering angry words. Cottolengo held him back, inviting the creditor to come and pray with him in the chapel. While they were reciting the litanies of the Blessed Virgin, a servant arrived and gave the Sister Portress two bags of coins with these simple words: “Thank Divine Providence.” While paying his due, Cottolengo told the creditor, “See how the Blessed Virgin immediately came to our assistance!” Stories like that were common at the Little House. Our Lady herself even came to comfort the Father after a difficult ordeal, as he once confessed to Sister Gabrielle, who had witnessed the visit of a most noble and regal woman.

Father Cottolengo foresaw the incredible expansion of the Little House. Within a few months, cafés and other buildings in the surrounding area were bought and transformed. A sort of village took shape, where each building was given a meaningful name: “House of Faith,” “House of Hope,” “House of Charity.” True communities developed, on the model of families, made up of volunteers: men and women, religious and laypeople, united in facing and overcoming the difficulties that arose. In 1833, three pavilions opened for epileptics, and two more for orphans. In 1834, two new homes started taking in the mentally ill, whom the founder called “good children.” In the following years, the Little House would welcome the deaf, young people in trouble and abandoned children who were educated in all areas: “Study the catechism well,” the Father told them, “and live according to its teachings. The catechism is everything: if you know it well, you know enough; if you don’t know it, you know nothing.” The homes were equipped with workshops so that convalescents could avoid idleness and learn a trade.

When some miserable wretch was referred to him, Cottolengo would reply, “If he’s a good-for-nothing, we’ll take him!” If the person’s situation was a new one, the Father would create a new “family” of the sick or needy. When advised to be careful, he would retort: “It is not up to us to look for the causes of the illness. We only know that someone is sick, with an illness that no one else will be willing to treat. Therefore, it was Providence that sent this person here.” He told those who worked at his side: “Those who you should cherish most are the most abandoned, the most repulsive, the most unwanted. They are all precious pearls. If you really understood whom the poor represent, you would serve them on your knees.” He was guided by a deep conviction: “The poor are Jesus, not his image. They are Jesus in person and they should be served as such. All the poor are our masters, and those who are most repulsive at first sight are even more our masters, they are our true treasures.”

Close relationships

According to Pope Benedict XVI, “From the outset, a fundamental principle of Saint Joseph Benedict’s work was the exercise of Christian charity for all. This permitted him to recognize great dignity in every person, even those on the fringes of society. Cottolengo had understood that those hit by suffering and rejection tend to withdraw and isolate themselves and to express distrust of life itself. Thus, for our Saint, taking on the burden of so much human suffering meant creating relations of affective, family, and spontaneous closeness by opening establishments that would favor this closeness in that family style which still endures today” (Turin, May 2, 2010).

The untimely death of Marianna Nasi in 1832 did not stem the increase in the number of Vincentian nuns. The Brothers of Saint Vincent worked alongside them. Don Cottolengo also came to found five monasteries for contemplative sisters and one for hermits. In the monastery for deaf Sisters, the Blessed Sacrament was exposed day and night for adoration. The founder viewed these houses of prayer as the most important of his achievements, as the “heart” that must beat for the totality of the Work. A seminary was also established for the specific training of priests for the Piccola Casa. In 1838, a school for professional nurses followed. After many prayers, the Father decided to open an asylum for women victims of debauchery in 1840. The redeemed sinners, who soon numbered thirty, were noted for their fervor and mortification. The libertines were annoyed and sent Cottolengo death threats. He was beaten several times and on one occasion received a serious chest wound, that would mark the beginning of slow deterioration of his health.

Everyone at the Little House had a very specific assignment: one to work, the other to pray; yet another to serve, instruct, or look after the administration. But most of all, there was a lot of praying: the sick, children, and nuns took turns in the chapel throughout the day. For the founder, the communion of saints was not a disembodied idea.

During his visit to the Little House, Pope Benedict XVI emphasized the role of the sick: “Dear sick people, you are carrying out an important activity: by living your suffering in union with the Crucified and Risen Christ, you share in the mystery of his suffering for the world’s salvation. By offering our pain to God through Christ, we can collaborate in the victory of good over evil, because God makes our offering, our act of love fruitful. Dear brothers and sisters… do not feel irrelevant to the world’s future but rather feel that you are precious pieces of a most beautiful mosaic that God, like a great artist, continues to create day by day, also with your contribution. Christ, who died on the Cross to save us, let himself be nailed to it so that life in its full splendor might blossom from that wood, from that sign of death. This house is one of the ripe fruits that the Cross and Resurrection of Christ have produced and shows that suffering, evil and death do not have the last word, for life can be reborn from death and suffering” (May 2, 2010).

Another spirit

Cottolengo, whose life was so full of material works, who cared for the sick and often spent recreation time playing with the mentally handicapped youngsters, also had a contemplative soul: he spent nights long in prayer. He never took an important decision without praying over it. Of his “families,” he asked that they should seek only the glory of God and holiness. “It is not forbidden to pray for something in particular,” he said. “The Church gives us an example of this when she makes us ask for earthly goods. But another spirit should drive us. Our Lord has taught us to first seek the kingdom of God and His justice; and all these things shall be added on to us. For me, the way to follow is absolute trust. We must not just believe in Providence; we must throw ourselves into its arms… Providence knows better than we do what is right for us.” But on some days, heaven seemed to be shut. More than once, Cottolengo was overwhelmed by debts. Creditors came after him and he was summoned to court. “You think I’m on a bed of roses,” he wrote to his brother; “Not at all! If I listened to myself, I would stop all of this. But God wants this from me. Woe to me if I stop working! If I stop, I hear the reproaches of the poor.” When donations dwindled, he would say, “If Providence lets us lack something, it cannot come from Providence; it is surely our fault. Let us examine our consciences, there is surely some sin among us!” One day, he cried out in the middle of a sermon: “Sin exists in this house. It is in our midst. One of us has deeply offended the Lord… This person should leave at once, or reform and make amends. At the Little House, sin is a great injustice, a dark ingratitude. Do we not live in a house that is overwhelmed every day by the weight of God’s bounties, a house that each day witnesses the renewal of the miracle of the multiplication of the loaves?”

Don Cottolengo was not a sad saint. He was always smiling, prancing around, and ready for a joke, spreading joy all around him. The poor people who were hospitalized at the Piccola Casa always sought out his company: “Just seeing him is enough,” they said. “His presence consoles us and when on top of that he speaks to us, he gives us joy.” As he said to the Vincentian sisters, “You serve Jesus in the poor, in the sick, in the children. You should therefore always be joyful, for otherwise you would seem to receive our good Jesus reluctantly.”

An unusual invitation

In 1841, a typhoid epidemic broke out in Turin. Many residents of the Little House fell ill, and six of the ten priests serving the institution died. Cottolengo was spared, and he devoted himself tirelessly. “All this has happened because God wants me to be more detached,” he said. “Deep inside, I feel something unusual inviting me to go up to heaven. It is time to pack up to go in Domino (to the Lord).” But Providence was watching over him: he held on until his successor, Don Anglesio (the generous pharmacist from the early days who had since become a priest), had completely recovered from typhoid. By now the disease had hit Cottolengo: exhausted, he took leave of each one of his “families;” blessing them, he promised them his protection when he would reach heaven. He withdrew to the house of his brother, the parish priest of Chieri, near Turin. He was nearly fifty-six when he died on April 30, 1842. His last words were “Misericordia, Domine! (Mercy, My Lord!) Good and holy Providence! Blessed Virgin, it is your turn now!”

After his beatification in 1917, the “Italian St. Vincent de Paul” was canonized by Pope Pius XI on April 29, 1934. There are now thirty-five branches of the Piccola Casa in Italy. Cottolengo’s Brothers and Sisters are also present in Switzerland, Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, India, the United States, and Ecuador.

Not everyone can undertake such spectacular works, but each of us can do our part with small acts of charity and works of mercy in order to spread, wherever Providence has placed us, the love of God and the knowledge of the one and only Savior, Jesus Christ. The Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches, “Works of mercy are charitable actions by which we come to the aid of our neighbor in his spiritual and bodily necessities. Instructing, advising, consoling, comforting are spiritual works of mercy, as are forgiving and bearing wrongs patiently. The corporal works of mercy consist especially in feeding the hungry, sheltering the homeless, clothing the naked, visiting the sick and imprisoned, and burying the dead. Among all these, giving alms to the poor is one of the chief witnesses to fraternal charity: it is also a work of justice pleasing to God” (No. 2447).

At a time when many of our contemporaries place their hopes in earthly goods alone, let us ask, through the intercession of St. Joseph Benedict Cottolengo, the grace to seek first the kingdom of God and to trust in His divine Providence for everything. As the Saint put it: “God will respond extraordinarily to all those who trust extraordinarily in Him.”