February 26, 2020

Saint José Sánchez del Rio

Dear Friends,

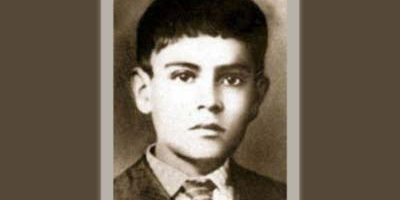

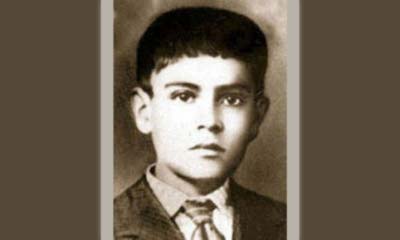

During the years 1926 to 1929, Catholics in Mexico faced violent persecution, resulting in many martyrs, some of whom have since been raised to the honor of the altar. On November 20, 2005, Cardinal Saraiva Martins traveled to Guadalajara, a large city in Mexico, to beatify thirteen of these martyrs on behalf of the Pope. In his homily, he said that “The feast of Christ the King has particular meaning for Mexican people. Pope Pius XI proclaimed it as a feast for the universal Church at the end of the 1925 Jubilee. Several months later, persecution against the Catholic faith began in Mexico, and a number of the Church’s sons died as martyrs, crying out, ‘Long live Christ the King!’ José Sánchez del Río should be mentioned in particular, because of his courage and his youth. Only fourteen, he bore courageous witness to Jesus Christ. He was an exemplary son: obedient, compassionate, with a strong spirit of service. When the persecutions in Mexico began, a desire to be martyred for Christ was born in him.”

José (Joseph) Sánchez del Río was born on March 28, 1913, in Sahuayo, a city in the State of Michoacán, in west central Mexico. His father, Macario, was descended from a Spanish family that had been living in the state for centuries. His mother, María, came from an ancient line of indigenous people called the Purhépechas. José had two older brothers, Macario and Miguel, as well as a little sister, María Luisa. The del Río family, deeply Catholic, had a prosperous ranch south of the city and was wealthy and well regarded. Doña Mariquita, as María was called, was known for her kind heart and boundless generosity. She was devoted to her household duties and raising her children. At the age of four and a half, José received the sacrament of Confirmation. He was a boy like others, given to play like other children of his age. His character was agreeable, lively, bright, and mischievous, and he was very easy, obedient, and affectionate with his parents. He gladly accompanied his mother to church and diligently studied the catechism.

José (Joseph) Sánchez del Río was born on March 28, 1913, in Sahuayo, a city in the State of Michoacán, in west central Mexico. His father, Macario, was descended from a Spanish family that had been living in the state for centuries. His mother, María, came from an ancient line of indigenous people called the Purhépechas. José had two older brothers, Macario and Miguel, as well as a little sister, María Luisa. The del Río family, deeply Catholic, had a prosperous ranch south of the city and was wealthy and well regarded. Doña Mariquita, as María was called, was known for her kind heart and boundless generosity. She was devoted to her household duties and raising her children. At the age of four and a half, José received the sacrament of Confirmation. He was a boy like others, given to play like other children of his age. His character was agreeable, lively, bright, and mischievous, and he was very easy, obedient, and affectionate with his parents. He gladly accompanied his mother to church and diligently studied the catechism.

Following the 1910 revolution, in 1917 Mexico adopted a new constitution. It contained several articles that were hostile to the Catholic Church, which began to be applied in some states in 1920. To avoid the persecution, the del Río family moved to Guadalajara, the capital of the State of Jalisco. There José made his first Communion at the age of nine. He was deeply devoted to Our Lady of Guadalupe, the Heavenly Patroness of Mexico, and gladly prayed the rosary.

“Long live Christ the King!”

In 1924, Plutarco Calles, an atheist and Freemason, was elected as President of Mexico. The following year, a schismatic Mexican church was founded by a priest, with the government’s support. The troubles for those who remained loyal to Rome intensified. Calles, inspired by Bolshevism, declared that the anticlerical articles were to be applied to the letter in all states starting on July 31, 1926. In response, the bishops voted to suspend services in all churches. Priests went into hiding. The government forbade them from celebrating Mass and giving the sacraments under pain of imprisonment or death, and public prayer was prohibited. The army enforced these laws. Within a few months, many Catholics were executed or imprisoned for violating the prohibitions. Those who opposed the Calles laws were shot, hanged, or displaced. This violence angered the population, leading to an uprising of thousands of people across the country. Small groups of civilian fighters formed who became known as Cristeros, a name they considered an honor. Farmers, tradespeople, and public figures joined. While the officers of the federal army led their troops into combat with the cry “Long live our father Satan!” the Cristeros’ rallying cry was “Long live Christ the King! Long live the Virgin of Guadalupe!”

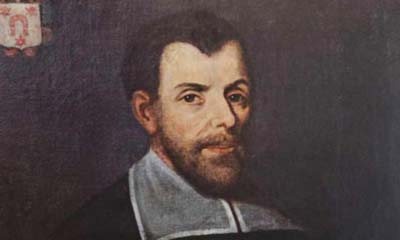

In Guadalajara, a young lawyer named Anacleto González Flores aroused Christian youth with his vibrant speeches. After having received a strong Christian education, he devoted himself to defending the most vulnerable. Knowing well the Church’s social doctrine, he sought, in the light of the Gospel, to protect the fundamental rights of Christians and founded the Popular Union to oppose the anticlerical laws. He was cruelly assassinated on April 1, 1927, at the age of 38. As he fell, he cried out “I die but God does not! Long live Christ the King!” Also spilling their blood that day were other members of the Popular Union—the brothers Jorge and Ramón Vargas González, and Luis Padilla Gómez. Their names were on the list of the thirteen martyrs beatified on November 20, 2005. “Among the key rights that Anacleto González and his fellow martyrs defended,” said Cardinal Martins, “was the right to freedom of religion, a right that is essential to human dignity itself. As the Second Vatican Council affirmed, ‘in regards to religion, no one should be forced to act in a manner contrary to his own beliefs nor prevented from taking action, within due limits, whether privately or publicly, whether alone or in association with others’ (Dignitatis Humanæ, No. 2). Bolstered by a deep love for Jesus Christ and neighbor, these new Blesseds defended this right peacefully, even at the price of their lives… Anacleto González and his fellow martyrs sought, to the greatest extent possible, to be the architects of forgiveness and a source of unity during a time of great division.”

To gain Heaven

After Anacleto’s assassination, José’s two older brothers joined the Cristero uprising under the command of General Ramírez, who oversaw the region of Sahuayo. That same year, in 1927, the del Río family returned to Sahuayo, where the population supported the Cristeros. Wealthy families offered financial assistance, weapons, and food. Priests risked their lives to offer the sacraments. José also expressed the desire to give his life for the cause. During a pilgrimage to Anacleto’s grave, he asked for his intercession that he might attain the grace of martyrdom. Not old enough to follow in his brother’s footsteps, he nonetheless asked to join the Cristeros, but his parents strongly objected. As months passed, José’s determination to join the resistance did not weaken. His mother continued to refuse, thinking him too young, to which he replied simply, “Mama, it has never been as easy to gain Heaven as it is today.” Nothing could dissuade him. He wrote to the leaders of the Cristeros asking for admission. Their repeated refusals—since he was only fourteen—only bolstered his resolve, until he finally obtained the consent and benediction of his father.

Enlightened by his faith, José ardently desired to attain Heaven, the sole goal of all human life. In his Rule, Saint Benedict tells his monks “to long for eternal life with all spiritual desire” (Chapter 4). The Catechism of the Catholic Church states: “This perfect life with the Most Holy Trinity, this communion of life and love with the Trinity, with the Virgin Mary, the angels and all the blessed is called ‘Heaven.’ Heaven is the ultimate end and fulfillment of the deepest human longings, the state of supreme, definitive happiness. To live in Heaven is ‘to be with Christ.’ (cf. Jn 14:3). The elect live ‘in Christ,’ but they retain, or rather find, their true identity, their own name (cf. Rev 2:17)” (Nos. 1024-1025).

In the summer of 1927, with the support of his aunts María and Magdalena, José went to the Cristero camp in Cotija with Juan Flores Espinosa, an adolescent with the same ideals. Despite obstacles, the two boys met the famous General Prudencio Mendoza, who warned them of the dangers of war and the hard life in the camps. José responded that he could help the soldiers with various tasks in camp: taking care of the horses, preparing meals. Noting the resolve and sincerity of their offer, the general placed the two teenagers under the command of Cristero leader Rubén Guízar Morfín.

Flag-bearer and bugler

José immediately began to serve his brothers in arms, fulfilling his role with deep charity and admirable dedication. His attitude and virtues won him the esteem of all, and his religious fervor and bravery were praised. José feared that President Calles’ supporters would take retribution on his family if they learned of his activity, so he added Luis to his name, becoming José Luis, and so would he be called for posterity. On the evening of December 12 (the feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe), in front of all of his men, General Guízar said to him: “Come here José Luis. As a sign of my trust, I officially appoint you flag-bearer and bugler of the unit. As bugler you will help convey my orders to the fighters. This means that you will go out with the troops on reconnaissance missions to observe the enemy.” José Luis was overcome with joy.

In early 1928, ambushes intensified in the region of Cotija. On February 6, during a serious clash with federal troops, General Guízar’s horse was shot, putting his life at risk. In an act of heroism, José Luis cried out, “My general, take my horse and save yourself. You are more important to the cause than I!” Guízar escaped, but José and a companion Lazarus were taken prisoner. They were brought to Cotija and presented to General Guerrero, one of the most ferocious persecutors of Cristeros. Despite blows, José let escape no complaint; he sought in prayer the strength to withstand the humiliations and torments. The general severely reproached him for fighting against the government, then invited him to join his troops. The adolescent replied without hesitation: “Fight for you? You are dreaming! I am your enemy! I would rather die!”

Surprised by so much fervor and humiliated by his refusal, Guerrero had José imprisoned. In his cell, José realized it was time to prepare to give his life to God. That night, he asked his jailers for pen and paper, and wrote a letter to his mother: “My dear Mother, I was taken prisoner in battle today. I now think I will die, but it doesn’t matter, mama. Resign yourself to the will of God; I die very happy, because I die faithful to Our Lord’s commandments. Do not worry yourself about my death… and tell my brothers to follow the example that their youngest brother leaves them, and do the will of God. Be brave and send me your blessing along with father’s. I greet everyone for the last time, and you, receive a last time the heart of your son who loves you so much and who wanted to see you before dying.”

The next day, on February 7, José Luis and Lazarus were transferred from Cotija to Sahuayo, because Guerrero had just learned that José was none other than the son of the rich and well-respected Macario del Río. José’s godfather for his first Communion was the Deputy Rafael Picazo, a local political leader who was a Calles sympathizer known for his ruthless opposition to the Cristeros. Picazo offered José several opportunities to flee abroad, then proposed that he enter to military school to continue his studies, all in vain.

“Don’t touch Lazarus!”

The prisoners were then brought to Saint John’s church, which had been converted into a prison. Upon entering, José was horrified to see how the sacred place had been desecrated. In addition to the soldiers’ terrible behavior, straw covered the ground, horses were tethered here and there, and a chapel was used as a chicken coop. Worst of all, the tabernacle had become a roost for the deputy’s fighting cocks, and the altar was soiled with their droppings. When night fell and the guards fell asleep, José managed to free himself. He killed the roosters and cleaned the altar. When he learned of this, Picazo entered in a fury. He asked José if he understood the gravity of his actions. The teen calmly replied, “The house of God is for prayer, not to house animals!” When the deputy threatened reprisal, Jose replied, “I am ready for anything. Shoot me, so that I can go immediately before Our Lord and ask Him to stop you!”

Picazo ruthlessly ordered his men to “Go get young Lazarus and hang him from a tree in the main square. José will watch the hanging.”

“Don’t touch Lazarus! He hasn’t done anything!” cried José. That evening, the prisoners were taken to the city’s main square, and Lazarus was hung from a tree before José’s eyes. He cried to his executioners, “Come, now kill me!” However, Lazarus did not die; thanks to a Good Samaritan, he was cared for and rejoined the Cristeros.

José, whom they had sought to frighten, was brought back to the church-prison. Locked in the baptistery chapel, from time to time he climbed to the small window to watch passersby. Recognizing him, several were able to exchange a few words with him. They later testified that José was at peace and spent his time praying, saying the rosary, and singing the praises of God. Because of his young age and his father’s position, the political and military authorities considered releasing him in exchange for a large ransom. Picazo seemed at first to be in favor of such an arrangement. Informing Don Macario of his son’s imprisonment, he told him that if he wished ever to see him again, he would have to pay 5,000 pesos. Terribly distressed, José’s father did everything he could to save his son; he was ready to sell everything he owned. When José learned of the proposal, and that he would in any case have to publicly renounce his faith, he said no to it all: “For the love of God, tell my father not to give a cent to Picazo, for I have offered my life to God.” The deputy, who could not tolerate that his friends, the Sánchez del Río family, had taken a position against the government that he represented, hardened towards their child, to the point of finally demanding that José die.

Communion as Viaticum

On Friday, February 10, around 6 PM, José was led to an inn called the Refuge, which had been turned into a prison. There he was told that he would be executed that night. José immediately asked for a pen and paper to write to his aunt María: “My dear aunt, I have been sentenced to death. At half past eight this very night the moment that I have so greatly desired will come. I thank you and aunt Magdalena for all you have done for me. I am not capable of writing to my dear mama. Please write to her for me, as well as to my little sister María Luisa. Tell aunt Magdalena that I have gotten my guards to let her come to see me one last time, so that she can bring me Communion as Viaticum. I think she will not refuse to come. Greet all my family, and you, receive as always and for the last time the heart of your nephew who loves you dearly and would like to see you again. May Christ live, may Christ reign, may Christ govern! Long live Christ the King and Our Lady of Guadalupe!—José Sánchez del Río, who died in defense of the faith. Please come! Farewell!”

Magdalena arrived in time to give him Communion, but José’s martyrdom was far from finished. Knowing that he had a great deal of information about the Cristeros, his jailers stripped the skin from the bottom of his feet to obtain some names from him. But the Lord gave him strength, and José gave no one away. At 11 PM, he was led to the cemetery, forced to walk barefoot. He cried with pain. His executioners tried to make him renounce his faith, whipping him with the branches of thorn bushes, but in vain. Nonstop, José shouted with all his strength: “Long live Christ the King and Our Lady of Guadalupe!” Hidden witnesses watched the scene with profound admiration, praying for him. He was promised he would be let go if he?would agree to say, “Long live the government!” In response, José began to sing, “To Heaven! To Heaven! I want to go to Heaven!” To shut him up, one of the soldiers struck him with a rifle butt, fracturing his jaw. At the edge of his grave, José continued to shout continually: “Long live Christ the King!” The soldiers stabbed him, and with each blow, in a weaker and weaker voice, José continued to profess his faith. The officer asked him cruelly: “Do you want to send a message to your father?”—“We will see each other in Heaven!” replied José, in one breath. “Long live Christ the King! Long live Our Lady of Guadalupe!”—“Ah! what a fanatic!” muttered the soldier, pulling out his gun and shooting him in the back of the neck. José, not yet fifteen, received the palm of martyrdom that Friday night, February 10, 1928, at 11:30 PM. Some Christians collected his body, washed it, wrapped it in a sheet, and after rendering their last respects, buried him.

“The young Blessed?José Sánchez del Río,” said Cardinal Martins on the day of his beatification, “must encourage us, and especially you, the youth, to be a witness to Christ in your daily lives. Dear young people, Jesus Christ will probably not ask you to spill your blood, but he does ask you to bear witness to the truth in your life, in a climate of indifference towards transcendent values, and materialism and hedonism that seek to stifle our consciences.”

Changing ourselves

The martyrs of Mexico gave their lives so that Christ could reign over their country. The Catechism of the Catholic Church reminds us of “the kingship of Christ over all creation and in particular over human societies” (No. 2105). Indeed, human reason can understand that societies, just like individuals, are dependent on God for all the benefits they receive from Him. In return, they have a public duty of praise, demand, recognition, and even reparation. For as public authorities they depend on God for their benefits. The exercise of this kingship begins of course by working on oneself, which is the first condition for effective action in the service of a Christian civilization, inspired by love. Saint John Paul II said: “Do not make the mistake of believing that we can change society simply by changing the external structures or by seeking the satisfaction of material needs above all else. We must begin by changing ourselves, by opening our hearts sincerely toward the living God, by morally transforming ourselves, by destroying the roots of sin and selfishness in our own hearts. A transformed person can effectively contribute to the transformation of society” (Homily on October 10, 1984, in Zaragoza, Spain).

In 1996, José’s mortal remains were transferred to the chapel of the baptistery where he had been imprisoned. Blessed José Sánchez del Río was canonized in Rome on October 16, 2016. May the young Mexican martyrs, who distinguished themselves by their intense Eucharistic life and their filial devotion to the Blessed Virgin under the title Our Lady of Guadalupe, help us bear witness to our faith in all circumstances! May Christ the King, the Good Shepherd, reign over the Nations, over all peoples, in all hearts! Long live Christ the King! Long live the Virgin of Guadalupe!