February 5, 2019

Lisa Guidotti

Dear Friends,

“It is to Mary, Mother of tender love,” wrote Pope Francis, “that we wish to entrust all those who are ill in body and soul, that She may sustain them in hope. We ask Her also to help us to be welcoming to our sick brothers and sisters. The Church knows that she requires a special grace to live up to her evangelical task of serving the sick” (Message for World Day of the Sick 2018, no. 7). The Virgin Mary granted to Luisa Guidotti the grace to use her medical expertise to serve those who were suffering, and to go so far as to give her life for them.

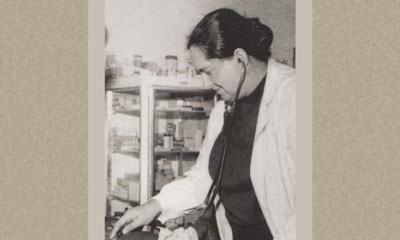

Born in Parma, in central Italy, on May 17, 1932, Luisa Guidotti came from a middle-class family. Her father was chief engineer for an Italian government office. The family spent winters in Parma and summers in the country, where the family owned a lovely second home. The girl was temperamental and stubborn. She was just fifteen years old when she lost her mother. The family then moved to Modena. Luisa was not interested in worldly life, but preferred to dedicate her free time to the parish, particularly in the Young Women’s Catholic Action, of which she became the local president, and later on the diocesan director. Since childhood, her ambition had been to become a missionary doctor. After finishing secondary school, she enrolled in the medical school in Modena. “It was the years before the council,” she would later write, “when the laity was becoming aware of its opportunities within the Church—I wanted to leave on mission as a doctor, a lay person among lay people.”

Born in Parma, in central Italy, on May 17, 1932, Luisa Guidotti came from a middle-class family. Her father was chief engineer for an Italian government office. The family spent winters in Parma and summers in the country, where the family owned a lovely second home. The girl was temperamental and stubborn. She was just fifteen years old when she lost her mother. The family then moved to Modena. Luisa was not interested in worldly life, but preferred to dedicate her free time to the parish, particularly in the Young Women’s Catholic Action, of which she became the local president, and later on the diocesan director. Since childhood, her ambition had been to become a missionary doctor. After finishing secondary school, she enrolled in the medical school in Modena. “It was the years before the council,” she would later write, “when the laity was becoming aware of its opportunities within the Church—I wanted to leave on mission as a doctor, a lay person among lay people.”

Doctors for the mission

During her studies, while she was attending a missionary congress, Luisa discovered the Women’s Medical Missions Association, recently founded (1954) by Adele Pignatelli. Bishop Giovanni Battista Montini, the future Pope Paul VI, had played a significant role in establishing this foundation; Adele had met him when he was serving as chaplain to the Italian Catholic Federation of University Students (FUCI). From her contact with him the idea had gradually emerged to found a new religious family, for doctors destined to work in mission lands. In 1960, at the end of her studies, Luisa asked Adele to be admitted to the association as an auxiliary member, that is, with a provisional commitment. The foundress advised her to choose a specialty, and Luisa chose radiology. She completed these additional studies in December 1962. In the meantime, Luisa opened a Women’s Medical Missions Association house in Modena for students from mission countries. She also expressed the desire to become a full member of the association, but Adele advised her to wait. In 1962, during a trip to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), Bishop Montini visited an unassuming health clinic that had been established on a huge sugar cane plantation, close to Chirundu. He suggested to Adele that she make this into a medical mission. Adele agreed without hesitation. After his election as Pope in June 1963, Paul VI received Adele and the missionary team heading for Chirundu. The Holy Father gave each member of the team a rosary and a cross. He sent them in the name of the Church, to represent Christ the Savior among the sick.

Luisa was not part of the team going to Chirundu. She had not yet completed her missionary formation, and her strong temperament made her full integration into the group of aspiring missionaries difficult. In the end, it was decided that she would complete her formation in the field, in Africa. After visiting her family in Modena, where the archbishop gave her the missionary’s cross, she left for Africa on August 9, 1966. On arrival, she wrote to the community back in Rome: “Chirundu is magnificent. Study hard, so that you will be ready to come soon. The Missions are a wonderful thing.” Oppressed by the heat and the mosquitos, Luisa faced exhausting hard work—in addition to the seventy patients staying at the clinic, both children and adults, there was the drop-in clinic, as well as three other clinics on the other side of the river, that had to be crossed by dugout canoe with all the necessary medical equipment. As many as a hundred patients could come in a single day.

Precious legacy

“The memory of this long history of service to the sick is cause for rejoicing on the part of the Christian community,” wrote Pope Francis. “Yet we must look to the past above all to let it enrich us. We should learn the lesson it teaches us about the self-sacrificing generosity of many founders of institutes in the service of the infirm, the creativity, prompted by charity, of many initiatives undertaken over the centuries, and the commitment to scientific research as a means of offering innovative and reliable treatments to the sick. This legacy of the past helps us to build a better future, for example, by shielding Catholic hospitals from the business mentality that is seeking worldwide to turn health care into a profit-making enterprise, which ends up discarding the poor. Wise organization and charity demand that the sick person be respected in his or her dignity, and constantly kept at the center of the therapeutic process. This should likewise be the approach of Christians who work in public structures; through their service, they too are called to bear convincing witness to the Gospel” (Message of November 26, 2017, for World Day of the Sick 2018, no. 5).

Since 1965, Rhodesia had been in a state of war. Ian Smith’s government in Salisbury had rejected the decolonization process and had declared the country’s unilateral independence from England. It was not long before Rhodesians of African origin, inspired by Marxism, formed guerrilla groups. First, the border with neighboring Zambia was gradually closed, blocking many Zambians from access to care at the clinic in Chirundu. Then, since the company that was managing the plantation had decided to go into exile in Zambia, the clinic found itself completely isolated. Having lost her job, Luisa was sent to Salisbury for additional training in pediatrics. With her somewhat unkempt appearance and her dreadful English, Luisa stood out among the English-speaking medical staff, which caused her suffering. Thirty-four years old at that time, with a specialist’s degree, she wrote to her superior: “I am still in the apprenticeship phase (of life at the hospital), but, as the Pope said, ‘initial sacrifices will make apostolic work fertile.’”

In 1967, Luisa returned to Italy. To her great joy, she was allowed to make her first vows. Returning to Rhodesia in 1969, she was put in charge of an area in Nyamaropa, which included the rural Regina Cæli Mission hospital and a leper colony. She wrote, “I am quite well at Regina Cæli. I do not at all understand why before now I could accomplish nothing, while here everything is smoothly rolling along.” She could not have been more dedicated. The clinic had received a child whose condition required care that the clinic could not provide. Luisa did not hesitate—she traveled approximately 160 km of trails at night to take him to a better equipped center.

We lack everything here

In December 1969, she was sent to “All Souls Mission” in Blantyre (150 km north of Salisbury). The mission consisted of a church served by two Jesuit Fathers assisted by a small community of Sisters, a school, a clinic and a rudimentary country hospital. Luisa wrote to her fellow Women’s Medical Missions Association sisters who had remained in Rome: “I have arrived at the new mission. Here all are Africans, even the Sisters and the priests. The hospital has buildings with roofs and walls, but not much else. I am assisted by two nurses. We three have knowledge but little experience. We lack everything here… Ninety-six beds are already on their way. As for money, we don’t have much. We are forced to cut corners on everything. We need more staff, and are considering starting a school to train nurses. When transfusions are needed, we ask for blood from the patient’s relatives. But when that isn’t enough, the sisters, the priests, the nurses, we all become donors.” Thanks to donations collected by the Women’s Medical Missions Association in Italy, Luisa was quickly able to set up basic equipment. Shortly before her death, she would obtain an electrical generator and an x-ray machine. During acute epidemics of malaria, a disease transmitted by the bites of mosquitoes, this hospital would accommodate as many as 150 patients. In the years that followed, local farmers were encouraged to raise chicken and rabbits to supplement the diet.

In another letter, Luisa explains that the local culture recognizes two major roles for women in society—that of mother and of grandmother. When they were speaking to her, patients regularly called her “doctor,” and sometimes, in a respectful and affectionate manner, “ambuya,” grandmother. She relates again: “In the missions, life is simple and joyous, even if there is too much work to do. I am happier than I’ve ever been. The Lord has been good to me. I love the people, I love my patients, and they love me. And this love will grow until it reaches the fullness of Christ’s love.” In 1975, despite much advice to the contrary, Adele Pignatelli, the superior general, allowed Luisa to fully join the community, to her great joy. From that point on, her devotion only grew. She also began to serve lepers in Mtemwa, fifteen kilometers from Blantyre, where she showed her missionary role in its fullness, bringing the joy of Christ there, and leading others to love Him and give themselves to Him.

At the beginning of the 1960s, there were approximately 600 lepers in Mtemwa being well cared for. Later on, a new treatment made it possible to cure most of them, although it did not repair the horrible ravages the disease had already wrought. The government decided at this time to send home the patients who had been cured and to dismantle the infrastructure. However, seventy former patients had not found anyone to take them in. A meager sum was allocated to provide for their food, and a warden was placed in charge of the village. This warden quickly proved to be a heartless man. Little by little, each member of this community withdrew into the solitude of his misery. Informed of this situation, the local superior of the Jesuits arranged for the warden to be dismissed immediately, and found an exceptional person to replace him: John Bradburne. A descendant of Baden Powell, the founder of scouting, and a former officer in the British army, he had fought the Japanese in Malaysia and Burma. Marked by terrible experiences, he had become a pilgrim hermit, continually traveling, until Providence brought him to Mtemwa. At once he felt the desire to dedicate himself to the unfortunate lepers: “Me, the eternal reject,” he said, “here at least I will be welcomed among these rejected ones.” Appointed warden, this man, “God’s vagabond,” brought them the human warmth that had been lacking.

A beautiful collaboration

After outfitting her clinic/hospital in Blantyre, Luisa began to explore the territory, and simultaneously discovered the leper colony and its leader, John Bradburne. The first contacts were not easy. Luisa’s demeanor was often somewhat brusque, even domineering, and John, as a result of his past experiences, had become very sensitive. They soon came to know one another better, and a beautiful collaboration began. Luisa examined the inhabitants of the village, one by one, and found that twenty of them were still sick and contagious. As for those who were cured, they suffered from various diseases, but many of them had never had leprosy!

A young woman who had attended the mission school as a student, Elisabeth, became friends with the devoted group alongside Luisa, and occasionally helped them. But her great sensitivity around the patients posed an obstacle to her admission. The first time she was taken to the leper colony, she was so terribly disturbed that for six months she refused to return. Later on, she managed to overcome herself completely, to the point that she could be admitted to the Women’s Medical Missions Association community. As a native, she was a great help, especially in overcoming difficulties in communication. Thanks to her, the little group brought the leper colony human warmth and divine love. The inhabitants of the neighboring town were stunned when they saw Luisa’s jeep pass by full of lepers that were being taken to the hospital for exams—they were singing and joyfully clapping their hands! Luisa wrote: “I have a serenity and joy now that I would never have been able to imagine. The Lord is good. I am nothing at all, but it is in my poverty that His strength has reached me most forcefully. … I am much happier now than when I was twenty.”

Committed to her patients

Around this time Father David Gibs reported to the mission. Born of European parents and raised in Rhodesia, he had just been ordained a priest, and his first mission was All Souls, where he arrived in 1975. He described Luisa as having an unaccommodating manner “with her hair pulled back and tied up on the back of her neck, and always dressed in dark clothes.” This first impression disappeared right away. Louisa in fact was easy-going and affectionate, always ready to chat, without worrying about the work that remained to be done. She helped people, as much as an affectionate advisor as an attentive doctor. “She was totally disorganized,” he would say. “Time did not exist for her. If she was immersed in reading a medical article, or studying ways to improve the quality of care in the mission, nothing could distract her, and patients sometimes had to wait for hours. When she finally appeared, she saw all the patients one by one, without worrying about the time. In the end, no one was upset about her delays… Every time she was running late, she apologized with such humility that people were forced to forgive her… Her skill as a doctor was exceptional. I have never known anyone who was as committed to her patients as Luisa was. Nothing was too tiring for her. I never saw her refuse to help someone, no matter who it was or what time it was. Often she slept only a few hours a night.”

“Sometimes we would go to a little clinic run by an African Sister. From the moment she got on the overloaded bus, everyone greeted her, and it was often a rather elderly man who offered his seat to her. Everyone was happy to see her. Many had benefited from her care, either themselves, or relatives or friends. Immediately it was as though a joyful family had formed around Luisa, and she was the mother. This was my impression of her—a woman profoundly alive and happy, loving people, loving her occupation and her role as a missionary, willing to endure all the blood, sweat and tears to serve these people she loved. The five-hour bus ride was difficult, but there was still more walking before arriving at the clinic. Luisa immediately set to work, attentive to each of the patients, who had sometimes traveled many kilometers on foot. After having cared for the last of them, she went to bed, to get up again at four thirty in the morning, take the bus back at six and start again elsewhere… She also taught at the nursing school.”

However, the Communist rebellion was spreading. Already in 1972, the superior of the mission had prohibited Luisa and her colleagues from visiting certain remote villages that were considered too dangerous. Shots were sometimes heard not far from the mission. Luisa wrote to her superior in Rome: “We are at peace and, for now, not afraid: the Lord is my shepherd and there is nothing I shall want (Ps. 22). The sentence that you sent me has done me a great deal of good: ‘Be careful, but charity prevails over caution.’” And also: “It seems to me that our presence is important. The young Christianity in Rhodesia must feel that the Church is close to her when people are suffering, and that she is not tied to any political system.”

In May 1976, the mission found itself in the midst of a war zone—battles, flyovers by military helicopters… people, and even families, were injured by irresponsibly placed anti-personnel mines. On June 24, a young man, wounded by bullets, was brought to the mission. Luisa and the others took care of him without asking any questions. A short time later, he left on foot, accompanied by a Brother to take him to a better equipped hospital. On the way, he was arrested and suspected of being a rebel. Shortly thereafter, the police arrived at the mission, and accused the nursing staff of helping rebels instead of reporting them as terrorists. Four days later, an entire police detachment arrived. Luisa was arrested. After intense suffering, even though she was not ill-treated physically, she was granted a provisional release thanks to numerous interventions, including by Pope Paul VI himself, who, informed of the facts, intervened before the trial.

Moral solitude

Luisa triumphantly returned to the mission while awaiting her trial. The village was declared “protected” by governmental forces, and surrounded by barbed wire. A military contingent was permanently placed there. However, fighting took place, even in the village, when rebels stormed in. The rebels tried to spare the hospital buildings, but were not always successful. Refugees flooded in; the Red Cross stepped in, feeding as many as 7,000 people in this “protected asylum”. In February 1977, seven missionaries were murdered in an area a short distance away from the mission. Civil war was raging. The police harassed the mission, which was suspected of providing (medical) assistance to the rebels. Once, Luisa said to the police chief: “I would care for even you myself, if you had a heart attack in front of me. Know that I am a doctor.” In 1978, she cared for the mother of Robert Mugabe, leader of the Communist rebels and future dictator of Zimbabwe. In spite of all the discretion surrounding this hospitalization, Luisa suffered its consequences. In 1979, most of the people were evacuated to less dangerous areas. Luisa refused to follow them, in spite of the invitation sent her by her superior general, who nonetheless did not want to order her, so as not to cause her a crisis of conscience. Luisa then found herself in great moral solitude, in spite of the loyal support of Father Gibs, who had also remained in the area. Two months before her death, she wrote to a friend: “It is hard to remain alone, without anyone to talk to. At times, I have the impression that I am useless and unloved. Then, the sadness and anger pass. Perhaps it’s necessary for me to learn to count on God alone. I have tried to achieve this trust and, out of nowhere, I have felt His real, though mysterious, presence. They can shoot me, but God is with me.” Another day: “It is beautiful to give a little more each day, to be completely and confidently in the hands of the Father, and to ask the Holy Spirit, Who is in us, to teach us to do the will of the Father.”

On July 6, 1979, as she was taking a patient to a hospital in an ambulance, against everyone’s advice. The vehicle was stopped by a military barricade “for inspection.” Suddenly, a burst of machine gun fire broke out—Luisa was fatally shot. She died a few hours later, before reaching the hospital. Luisa’s cause for beatification has concluded at the diocesan level, and has been sent to the Congregation for the Causes of Saints.

“May our prayers to the Mother of God see us united in an incessant plea that every member of the Church may live with love the vocation to serve life and health,” wrote Pope Francis. “May the Virgin Mary … help the sick to experience their suffering in communion with the Lord Jesus; and may She support all those who care for them” (Pope Francis, Message for World Day of the Sick 2018, no. 7).