June 11, 2020

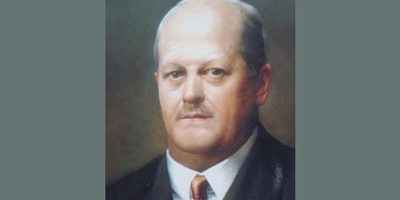

Blessed Ladislaus Batthyány-Strattmann

Dear Friends,

During a colloquium on Hungary in October 1996, Saint John Paul II gave vibrant homage to three Hungarian Catholics of the 20th century: Doctor Ladislaus Batthyány-Strattmann († 1931), Bishop Vilmos Apor († 1945), and Cardinal Josef Mindszenty († 1975). While the Pope recognized the last two as martyrs of resistance to atheist dictators, he described Ladislaus as a “hero of brotherly love.” In March 2003, Saint John Paul II raised this “doctor of the poor” to the honors of the altar.

Ladislaus Batthyány-Strattmann was born on October 28, 1870 in Dunakiliti (Austria-Hungary), 55 miles (90 km) east of Vienna, into an illustrious and wealthy family of the Austro-Hungarian aristocracy. His childhood was marked by heavy trials: first his father abandoned the family, and then before he was twelve his beloved mother died after a long illness. He was a mediocre student, and due to his bad behavior he had to change schools three times. In Vienna he first studied chemistry, then philosophy and astronomy, but his life had no purpose, and his irascibility irritated others. An irresponsible romantic relationship left him with a daughter whom he took care of all his life.

Ladislaus Batthyány-Strattmann was born on October 28, 1870 in Dunakiliti (Austria-Hungary), 55 miles (90 km) east of Vienna, into an illustrious and wealthy family of the Austro-Hungarian aristocracy. His childhood was marked by heavy trials: first his father abandoned the family, and then before he was twelve his beloved mother died after a long illness. He was a mediocre student, and due to his bad behavior he had to change schools three times. In Vienna he first studied chemistry, then philosophy and astronomy, but his life had no purpose, and his irascibility irritated others. An irresponsible romantic relationship left him with a daughter whom he took care of all his life.

At the age of twenty-five, however, there was a decisive change in his life. Contrary to the norms of his social milieu, he decided to adopt a “bourgeois” profession, and began medical studies. Deep reflection before God, and the errors of his youth, contributed to this conversion, which he also attributed to the patient intercession of a good priest he knew. Three years later, on November 10, 1898, he married Countess Maria Teresia Coreth, a union that produced thirteen children. A teacher recalled, “I never saw anywhere as close a family, or as loving and joyful an atmosphere, as in the Batthyány home.” Bit by bit, thanks to prayer, Ladislaus placed God in the center of his work as a doctor, his role as a husband, and the formation of his children. In 1926 he wrote, “In the first place, love is the adornment of life; God is love, and all noble love is a reflection of divine nature.”

In 1898, the young medical student built a modern hospital near his chateau in Kittsee, at the time in Hungary but which would be annexed to Austria in 1920. He put more than two-thirds of his income into this hospital to help his “dear patients.” In 1900 he received his medical degree, specializing first as a surgeon and later in ophthalmology. He was soon treating 80 to 100 patients a day, often himself paying not only for the medicines he prescribed, but for his patients’ travel expense. Although he spoke fluent German and Hungarian, he learned to speak Slovakian and Croatian to better communicate with all the residents of this border region.

In 1915, on the death of Prince Edmund, his uncle, Ladislaus received from Emperor Franz Joseph the title of prince. Ladislaus then left the hospital in Kittsee and moved with his wife and children to the family castle in Körmend, Western Hungary. He immediately opened another hospital, becoming the head physician. The Great War was in full swing: the prince hospitalized countless wounded soldiers, and, moreover, built for them a building that could hold a hundred beds. He never seems tired of caring for his patients. “Whoever visits me as a patient is already a friend, even before I meet him or her,” he said one day. It was nevertheless necessary for him to make an effort to leave his bad mood at the patient’s door. He strove to be patient, to listen attentively to his “dear patients,” and to treat their bodies with gentleness and respect. He knew he was only an instrument of God’s work, and wanted to heal not only the body, but also the soul. He began and ended his service to the sick each day with a visit to the Blessed Sacrament in the family chapel. Before each operation, he prayed to God for assistance. His wife, a certified nurse, often assisted at his operations.

“Mister Prince, I can see again!”

One of his aunts recounts, “One day, a man in rags who had fallen head first into a quick lime pit arrived at Laci’s (Ladislaus’) surgery—one eye had been instantly destroyed, and the other seemed untreatable; he was virtually blind. With a heavy heart, Laci operated on him immediately. A long hospitalization and two more operations followed. Laci and his large family prayed for him, and God heard their prayer; the day came when the patient ecstatically announced, ‘Mister Prince, I can see again!’ When the time came to leave the hospital, he broke down in tear and knelt before his ‘savior’. Ladislaus cried out, ‘No, don’t kneel before me!’ and he also dropped to his knees to thank God. We found both of them on their knees, thanking God. Laci then took some shoes and clothes from his own closet, dressed his patient in them, and wished him well.”

Doctor-Prince Batthyány was covered in honors: the Emperor received him into the Distinguished Order of the Golden Fleece and the Royal Hungarian Order of Saint Stephen, the Pope bestowed the Golden Spur upon him, the Hungarian people elected him to the Upper House, and he was inducted into the Hungarian Academy of Science. Despite all these honors, he fled the spotlight, not wishing to draw attention to himself. “Both greatness and simplicity were at home in him,” stated one of his frequent guests. He drew generously from his personal fortune for the welfare of his patients, as well as to support thirteen parishes and several schools. He raised his children with the ideals of humility and hard work.

Though very welcoming, the doctor nonetheless did not like worldliness. “He detested the small talk of salons, which easily turned to gossip,” his sister wrote. “He never spoke ill of others, and did not tolerate hearing such talk. If he was unable to prevent it, he left the room or managed to change the topic.” In his journal, Ladislaus wrote, “Every human being is worth only what he is worth in the eyes of God; the praiseworthy qualities are justice, truth, charity, and those others that flow naturally from the love of God.”

There was no separation between his spiritual life and his professional activity. In 1926, he wrote in his journal: “Several days ago I operated on a horrible cancer of the tongue. Yesterday, I attended the joyous birth of a child and healed three cataracts. Of all these joys and pains, modern humanity in lounge chairs, glass of sherry in hand, knows nothing. And yet, I would trade not places with anyone. Even if I were to be born a thousand times, a thousand times I would tell my good Lord in heaven: ‘Lord, let me become a doctor again, to work for You and your glory!’”

Even in the middle of the night

Doctor Batthyány’s professional zeal could be illustrated by many examples, for instance: a child was collecting pine branches for a school celebration; a large needle penetrated his eye. He screamed as though he were being skinned alive, but his sister ran to inform their mother in soothing terms: “Mommy don’t worry, nothing serious happened, Karl just stabbed himself in the eye.” Rushing over, the mother noticed a yellow liquid running from the wounded eye. “Quick, let’s go to the prince!” she ordered. But it was 4 o’clock in the afternoon and the surgery was already closed. That meant nothing! The doctor prepared the operating room and told the child’s father, who was ashamed of having disturbing the prince: “Even if it were the middle of the night, it would be my duty to help a sick person!” The operation was a total success; the child’s eye was saved!

“I love my job,” said the doctor. “The sick teach me to love God more and more, and I love God in the sick. My patients help me more than I help them! They pray for me, and obtain immense graces for me and my family. Thanks to the goodness of God, my patients have made me into another Simon of Cyrene who can help them with love to carry their cross.” As for his ophthalmology specialty, he wrote: “Because the eye is the mirror of the soul, when I have the chance, with God’s help, to enable someone to see the light of day again, usually I can also have an influence on their soul.” To patients who maintained contact with him, he sent a small brochure he titled “Open your eyes and see!” to help them open the eyes of their souls to spiritual realities.

When a poor patient would ask him, in embarrassment, how he could thank him for the free care, the doctor inevitably replied, “Say an ‘Our Father’ and a ‘Hail Mary’ for me.” It was not uncommon for a patient treated “pro bono” to return home with a “pain bonus”—alms that the doctor offered as “compensation” for the suffering they endured! His Jewish patients he asked to pray for him using prayers from their own Bible.

Pope Francis wrote, “‘You received without payment; give without payment’ (Mt 10:8). These are the words spoken by Jesus when sending forth his apostles to spread the Gospel, so that his Kingdom might grow through acts of gratuitous love. The Church—as a Mother to all her children, especially the infirm—reminds us that generous gestures like that of the Good Samaritan are the most credible means of evangelization. Caring for the sick requires professionalism, tenderness, and straightforward and simple gestures freely given, like a caress that makes others feel loved. Life is a gift from God. Saint Paul asks: ‘What do you have that you did not receive?’ (1 Cor 4:7). Precisely because it is a gift, human life cannot be reduced to a personal possession or private property, especially in the light of medical and biotechnological advances that could tempt us to manipulate the ‘tree of life’ (see Gen 3:24). I urge everyone, at every level, to promote a culture of generosity and of gift, which is indispensable for overcoming the culture of profit and waste. Catholic healthcare institutions must not fall into the trap of simply running a business; they must be concerned with personal care more than profit. We know that health is relational, dependent on interaction with others, and requires trust, friendship and solidarity. It is a treasure that can be enjoyed fully only when it is shared. The joy of generous giving is a barometer of the health of a Christian.” (Message on November 25, 2018, for the 2019 World Day of the Sick).

Do not forget your soul

When Doctor Batthyány’s Catholic patients left the hospital, he gave them a small picture of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. On the back was printed, “Take this image as a pious memory of our hospital, and if you think you owe thanks to someone, pray for us. You came to us to find a remedy for your body, but do not forget your immortal soul, which is so valuable that the Lord Jesus himself died on the cross for it. Life is very short, and we will soon find ourselves before God, who will judge us as we are. ‘What good is it for someone to gain the whole world, yet forfeit their soul? Store up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where moths and vermin do not destroy.’ Go quickly and receive the sacraments, for only good works can offer consolation in the face of death. Receive with an open heart these words that come from my love for you, think of them often, and may the Lord Jesus, whose image I have given you, bless you on the path of life!”

One of his patients, a distinguished woman who had surely known better days before the war, could not hide her poverty. She was happy, while at the hospital, to be able to eat her fill. At the end of her stay, Doctor Batthyány, who didn’t know how to help her without embarrassing her, suddenly had an idea: when she came to say goodbye, he said “Here, take this image of the Virgin Mary hanging on the wall. It is for you.” Touched, the lady took the picture and noticed that several large bank notes were slipped into the lining. Pretending to be surprised, Ladislaus told her, “You see, it is a gift from the Blessed Virgin!”

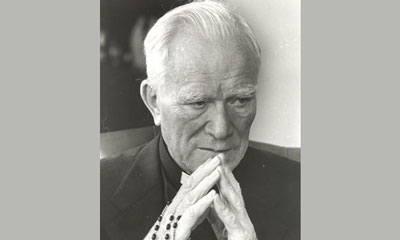

The religious life of the doctor, who was absorbed in his daily duty, was marked by an intense devotion to Mary, the Mother of God. He loved to pray the Rosary; in many photographs of him, a careful observer can note that he is discretely holding a rosary in his hand. From it he drew the strength to unite himself to God and to love his neighbor. Thus God was not an idea to him or an abstract concept, but someone entirely real and present. From December 20, 1905 on, the day of Pius X’s decree encouraging the faithful in a state of grace to receive frequent Communion, Ladislaus received communion daily at the Holy Mass with which he started his day. After a period of illness, he wrote in his journal, “Praise God! Today, on this Marian feast, I was able to once again attend Holy Mass and receive communion. A day without it is not good. Holy Communion is the best moment of the day!” His pastor wrote, “For the prince, the Eucharist is not simply a pious practice, but the real presence of Jesus to whom he could turn, could see, could joyfully adore.” He placed all his financial affairs and his family’s concerns in the hands of Saint Joseph. One day in 1914, confronted with the material suffering resulting from the war, he wrote, on the back of an image of Saint Joseph, a prayer of supplication, affectionately calling him “my minister of finances.”

A stained-glass saint

But Doctor Batthyány was not a stained-glass saint. One day, when he had worked at the hospital long past his usual lunchtime, he was walking quickly across the courtyard to his home when an unpleasant looking man blocked his path. Worn out by the intense work of his long morning, Ladislaus lost his patience and muttered, “Goodness, what is it this time? This is all I need! What do you want from me?” Completely unperturbed, the man kissed his hand and said: “Prince, I just wanted to thank you with all my heart for restoring my elderly mother’s sight. I’m here to bring her home.” Ladislaus was taken aback. The voice of his conscience said, “My dear Laci, what you have just said to this good man is not consistent with the First Epistle to the Corinthians that you cite so often: “Love endures all things’ (1 Cor 13:7).” Soon thereafter, in a letter to his sister-in-law, a Benedictine nun, Ladislaus recounted this event, commenting, “This man brought me roses, and I threw a cactus at him.” Drawing a lesson from the incident, he concluded, “I do not love my neighbor enough. The shortest path to the perfection of fraternal charity is to love the good Lord more.”

In 1921 Ladislaus faced the greatest trial of his life, the loss of this eldest son, Ödön (Edmond), a boy as intelligent as he was pious. After having saved so many lives, the doctor faced his own powerlessness in the face of the incurable tumor that afflicted his son. The young man, twenty-one years old, asked “Papa, am I going to die?” His heart torn, Ladislaus said to himself, “Should I tell him the truth, or leave him in ignorance so that he does not lose hope?” He finally replied softly, “The Good Lord’s power is infinite, while ours is limited. He can in an instant restore you to health, but medicine cannot save your life.” Nevertheless, in the hope of at least delaying the fatal outcome and to reduce his son’s suffering, the doctor gave him chemotherapy injections, but to no effect. After Edmond’s death, Ladislaus’ only consolation was the thought that he would see him again one day in Heaven. In 1926, looking back over his life, Ladislaus wrote in his journal, “I made one of the main tasks of my life to serve my human brothers by means of my medical skills, and thus offer to God what pleases Him. By his grace, I was able, over the long years, day after day, to work in my hospital for the good of my patients. This work was the source of countless graces and of the great spiritual joy that filled my soul and those of the members of my family. For this reason, I thank with all my heart—as I have always done throughout my life—my Creator for having called me to be a doctor.”

Even as he approached sixty years old, Doctor Batthyány refused to slow down. After consulting a cardiologist who implored him to spare his endangered health, he agreed to stop performing surgery and devote himself solely to ophthalmology. In September 1929, during a family vacation in Belgium, he met the exiled Empress of Austria and Queen of Hungary, Zita de Habsbourg, whom he admired along with her late husband, Blessed Charles I. On his return in November, cancer of the kidneys was discovered, and he was operated on in Vienna, but to no avail. The 14 months of illness, spent at the Löw sanatorium in Vienna, was for him a hard Way of the Cross. He admitted to his wife, “I am suffering enormously. I never would have thought a human being could suffer so much. But it is good. Everything that God wants is good!”

“Never say that again!”

A witness wrote, “His hospital room became a sort of place of pilgrimage, from which people left distressed and upset, but with their faith bolstered.” Many came intending to console him, but the effect was the reverse; they left healed of their spiritual wounds. His patience and goodness seemed so extraordinary that one of his children said to him one day, “Papa, you are a saint!” Horrified, he began to tremble and cried out, “I beg you, never say that again! I never want to hear such a thing again!” Plugging his ears, he raised his eyes to heaven as though to beg forgiveness for what his child had said and continued humbly, “I am so far from sanctity! I am a poor sinner!” And yet, the priest who came to give him last rites the night before he died later confided, with tears in his eyes, “Only a saint could make a confession like that which I heard!”

On January 22, 1931, Ladislaus Batthyány-Strattmann returned to God. The evening before, he asked his family, “Carry me onto the balcony, so I can cry out to the world, ‘God is good!’” The next day, a woman wrote an article in the local paper that concluded with this wish: “Just as you, my dear prince, allowed my son to see the light of day, may the Good Lord immediately admit you to the eternal light.” The apostolic nuncio to Vienna, Msgr. Schioppa, wrote to Pope Pius XI: “The people consider the prince to be a saint. I can assure your Holiness that he is!” Ladislaus Batthyány’s remains are in the church of the Franciscan monastery in Güssing, in the Austrian diocese of Eisenstadt, close to the Hungarian border.

During the beatification of Ladislaus, Pope John Paul II summarized thus the life of the one called the “Franciscan-Prince”, due to his love for the poor and poverty: “He used the fortune he inherited from his noble ancestors to treat the poor for free and to build two hospitals. He had no interest in material things, or success, or career… He never placed the treasures of earth above the real good which is in Heaven. May the example of his exemplary family life, anchored in the faith, and generous Christian solidarity encourage all to faithfully follow the Gospel!” Let us remember this advice from of Blessed Ladislaus, which is a striking summary of the Gospel: “If you wish to be happy, make others happy!”