June 28, 2019

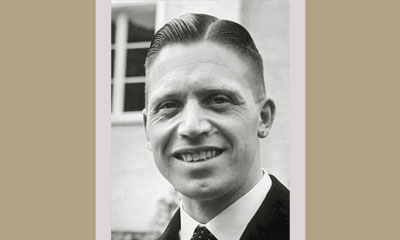

Blessed Joseph Mayr-Nusser

Dear Friends,

In 1980, Hildegarde Mayr-Nusser, a woman in South Tyrol who had been widowed for 35 years, received an unexpected letter from a former German soldier named Fritz Habicher: “Your husband died for Christ, I am sure of it. I am convinced that I spent fifteen days with a saint, who is now a great intercessor for me with God.” This soldier from Nazi Germany’s “Special Section” had led a train of prisoners condemned to death across Germany. Josef Mayr-Nusser, arrested for refusing to swear an oath of loyalty to Hitler, was one of them. He never arrived at his destination, dying en route. On July 8, 2016, he was decreed a martyr by the Roman Congregation for the Causes of Saints.

Josef was born in 1910 on Nusserhof farm, near Bozen (Bolzano in Italian), the capital of South Tyrol. His father was drafted into the army in 1914, and died the following year on the front. Maria, Josef’s mother, ably managed the family estate. Even though very busy raising her children and running the farm, she attended Mass every day. Prayers and the rosary were part of daily life for this family with six children. Jakob, the eldest brother, was ordained a priest in 1934. Josef, nicknamed Pepi, was a lively, playful, but unruly boy. To avoid being scolded by his mother, he forged his dead father’s signature on his report card. However, he rapidly improved and became a good student. He loved nature, but lacked the practical sense and skills required for farm work. His family’s modest means prevented him from pursuing higher education. However, he did obtain a degree from a business school in Bolzano.

Josef was born in 1910 on Nusserhof farm, near Bozen (Bolzano in Italian), the capital of South Tyrol. His father was drafted into the army in 1914, and died the following year on the front. Maria, Josef’s mother, ably managed the family estate. Even though very busy raising her children and running the farm, she attended Mass every day. Prayers and the rosary were part of daily life for this family with six children. Jakob, the eldest brother, was ordained a priest in 1934. Josef, nicknamed Pepi, was a lively, playful, but unruly boy. To avoid being scolded by his mother, he forged his dead father’s signature on his report card. However, he rapidly improved and became a good student. He loved nature, but lacked the practical sense and skills required for farm work. His family’s modest means prevented him from pursuing higher education. However, he did obtain a degree from a business school in Bolzano.

The 1919 Saint-Germain peace treaty gave South Tyrol to Italy, without consulting the German speaking population of this region, which until then had belonged to Austria. When Benito Mussolini took power in 1922, he instituted a policy of forced Italianization, changing place names and dictating that only Italian be used in schools and public places. The population passively resisted, discreetly preserving its languages and traditions. Josef studied Italian for his work, but at home and in church he spoke German or the Tyrolean dialect. Serious and studious, he read many religious books. His bedside reading included Saint Thomas of Aquinas’ Summa Theologica and the spiritual writings of the martyr Saint Thomas More. He became very active with the Catholic Action movement, becoming head of the local chapter. The Chaplain, Father Josef Ferrari, was his spiritual father.

Winning hearts

In 1931, Josef was drafted into military service and took the oath of loyalty required of all Italian soldiers. Pope Pius XI had authorized Catholics to take the civil oath by making the mental reservation, “except for the commands of God and his Church.” After 18 months of unenthusiastic service, Josef returned to Bolzano where he worked as a salesman for the Eccel company. In 1932, he joined the Saint Vincent de Paul society. He visited the poor, who were often elderly and neglected. In 1937, despite his young age, he was named president of a new chapter in Bolzano. He was well regarded for his social and organizational skills, as well as his spiritual depth. In an article in the “Saint Vincent Journal,” he shared his experience for others who visited the poor: “The ability to listen is the secret to winning hearts quickly. Often the brother is the only person the poor can speak with: how happy they are to see that someone understands their struggles and patiently listens to everything they have to say. Take the chair they offer, even if it is not very clean. Sit and listen with cordial openness to everything they have to say about their worries and distress. Suffering shared is suffering halved. This attentiveness is even more precious than any money we give. It enables them to see that we come as a disciple of the Savior who has taught fraternal charity, not Mr. X, a clerk giving out money.” Josef took care to insist, “It is not just a matter of providing the poor with material support. We have another responsibility: spiritual support for the poor… More than their temporal wellbeing, it is their eternal salvation we must put in first place.” In 1934, Josef was elected head of the young men’s section of Catholic youth for the German-speaking part of the Archdiocese of Trent. The Catholic youth meetings were discreetly held in isolated chalets, to avoid surveillance by suspicious police. Sport, games, singing, and music were an important part of these meetings, but the goal remained “the establishment of the reign of Christ in our nation.” In 1939, 72 Catholic youth organizations operated in the area under Josef’s authority. Every village was visited, to encourage the Christians there to persevere in their life of faith.

A clear assessment

In 1936, during the Auxiliary Bishop of Trent’s visit to Bolzano, the young leader gave a clear assessment of the situation: “Our region is almost 100?% Catholic if you look at certificates of baptism. But how many can truly be considered good Catholics? At best maybe 10?%. The old liberalism, which has infiltrated so deeply in the last century, remains firmly entrenched. Economic, social, and cultural life has been profoundly contaminated by this liberalism. For many Catholics, religious practice has become a duty to be dispensed with as quickly as possible… But we are Christians, and Christians must always remain optimistic. There is a movement among some youth who are disgusted with the superficial, materialistic, and hedonistic spirit of modern culture. These youth understand the ultimate goal of creation: the glory of God. They reject any separation between two visions of the world: a private life in which one is Christian, and a public life in which one is atheist. They seek to glorify God not only in private, but also in their daily work and social lives… It is only if we give God the glory due Him, not only at church but at work and in our public lives, that the second part of the message of Christmas will be realized: ‘…peace on earth to men of good will.’” Josef thus expressed his commitment to the teachings of the Quas primas and Quadragesimo anno encyclicals, recently issued by Pope Pius XI.

Frequent attendance at Mass was a fundamental component of his Christian life: “Participation in the sacrifice of the Mass and access to the Holy Table fortify us in our daily struggles against all the dark forces that threaten our salvation.” To this end, the youth of Catholic Action decided to restore a beautiful little church, Saint John. Father Ferrari gave them missals that included the Latin text along with a German translation, still relatively uncommon at the time.

The only “leader”

Three years after Adolf Hitler rose to power in Germany, Josef first alluded to the enthusiasm for Hitler among many Tyroleans: “This worship of the Führer (“leader”) that we see is often nothing other than paganism. Today, Catholic Action must show the masses that the only leader who has the right to unlimited authority and power is Christ. Two great currents are colliding: one whose motto is ‘the world for Christ,’ the other which honors Satan as its supreme leader.” The political rapprochement between Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy that began in 1936 culminated in the Pact of Steel, an offensive and defensive alliance between the two powers. South Tyrol, claimed by Germany, was the only point of disagreement. In October, Hitler and Mussolini reached a compromise: all South Tyroleans who wished could emigrate to Germany and be provided for; those who wished to remain must give up their culture and become “100?% Italian.” Of the German-speaking population of South Tyrol, suffering from the economic misery and vexations of fascist Italy, 80?% chose to emigrate to Germany (though many were unable to leave because of the war). Father Ferrari convinced the Mayr-Nusser family to stay. The South Tyroleans who did not go into exile decided to organize. In the fall of 1939, in great secrecy, they founded a movement called the Andreas Hofer Bund (after a hero of the Tyrolean resistance to Napoleon’s invasion) to defend Tyrolean identity and culture. Josef Mayr-Nusser joined this resistance and held secret meetings in his home.

In 1928, Josef began working closely with Hildegarde Straub, his manager at Eccel. Like him, Hildegarde was also active in Catholic Action. He asked her to marry him, but because she was from a higher social class, she hesitated. Yet Josef’s intelligence and heart won her over and they married on May 26, 1942. Thanks to Pius XI’s encyclical Casti Connubii (1930), Josef had a very comprehensive Catholic teaching on Christian marriage, which Jesus Christ had raised to the dignity of a sacrament, and on the complementarity between men and women. The newlyweds traveled to Rome for their honeymoon, staying at the Vatican. There they met a number of Jews sheltered by Pope Pius XII who were waiting for visas to the United States. Hildegarde appreciated her husband’s qualities, his affection, his loving presence, his patience, and his positive view of others, particularly the clergy, whom he refused to criticize. On August 1, 1943, little Albert was born, to their great joy.

But the political situation worsened dramatically. On July 9, 1943, the Allied Powers (the US and England) landed in Sicily. Fifteen days later, leaders of the fascist party toppled Mussolini. In September, under the impetus of King Victor-Emmanuel III, Italy surrendered and joined the allies. In response, the German army disarmed the Italian troops and occupied the peninsula. South Tyrol was part of the German Reich, which was now being attacked on three fronts by the Soviets and Anglo-Saxons. The Nazis conscripted the men of South Tyrol into the army. Even though he was an Italian citizen by choice, Josef was mobilized at the end of August 1944. To avoid retaliation against his family, he refused to avoid his service. But he expressed his fear of being enrolled in the Waffen-SS, Himmler’s parallel army. The SS were very fanatic and noted for their extreme brutality. Josef was determined to refuse at all costs any orders that violated his Christian conscience. On September 7, 1944, along with 80 other recruits, Josef left for Konitz, in Western Prussia (now Poland). Josef wrote to his wife: “Do not worry about me darling, for we are in God’s hands. Forgive me for speaking of material things, but I would be happy to receive some warm clothing, and also something to fill my stomach. The state of total war can be seen everywhere here in the Reich.”

A very painful thorn

Josef and his comrades were put through rigorous military training and subjected to constant indoctrination. To his great displeasure, they wore the SS uniform. He tactfully confided to his wife that he would refuse to swear the oath of unconditional loyalty to Hitler, adding: “The thought of the unhappiness my decision may cause you is a very painful thorn in my heart… But my certainty, my dear wife, that you understand me and share my view is a great consolation to me. Your prayer will strengthen me at the critical moment.” Yet Josef still hoped he could count on his superiors’ understanding, and dispense him from the oath, as had been done for one of his South Tyrolean comrades. At the end of the training period, the sergeant in charge of the company announced to the 80 recruits that the next day, October 5, they were to take the SS oath of loyalty. He read out the text: “To you, Adolf Hitler, Führer and Chancellor of the Reich, I swear loyalty and courage. To you and the leaders you designate, I swear obedience until death. So help me God!” Josef raised his hand and declared that he could not take this oath. The sergeant went to get the head of the unit, who asked Josef to explain his refusal. He replied that he could not take the oath for religious reasons. The officer asked him: “Are you not then 100?% National Socialist?” “No, I am not!” Josef calmly replied. The commander then told him to put his refusal in writing, which Josef did immediately, indicating “for religious reasons.” Petrified, Josef’s comrades felt that he had just signed his death warrant. A few days earlier, when Josef told his roommate, Hanskarl Neuhauser, that he intended to refuse the oath, Hanskarl replied, “I don’t think that the Lord our God requires that of us.” Josef responded: “If no one ever has the courage to say they don’t agree with the Nazi ideology, the situation will never change.” He knew this decision would cost him at least his freedom, if not his life, but his conscience demanded it. That very day he was imprisoned, and a trial for treason begun.

An urgent message

On November 12, Josef wrote Hildegarde a long letter to try to reassure and console her. He ardently wanted to see her and their little Albert again; he wrote that he was sure that their love would survive this hard trial to emerge even stronger. “My profession of faith will cause you immense suffering. The need for such a witness is now undeniable. Two worlds are colliding. My superiors have clearly shown that they reject and hate all that is sacred to us Catholics, and which we cannot renounce… Hildegarde, my dearest wife, be strong! God will not abandon us! When the Lord demands a sacrifice, he gives us the strength for it. ‘Who shall separate us from the love of Christ? Neither fire, nor sword…’ (Rom. 8:35). I have never experienced this as deeply as I do today… Here I have no friend with whom I can share my faith, no religious support; how this lack weighs on me! But oh how I am consoled by the thought of so many people praying for me back home!” On the 14th, he was transferred to Danzig to stand trial before a military tribunal. On December 5, he thanked his wife effusively for her letters, which the judge had given him. He encouraged her to remain hopeful and abandon herself to Providence. It would be the last she would hear from him. On April 5, 1945, Hildegarde received official word that “SS soldier Josef Mayr-Nusser has died at Erlangen station from bronchopneumonia.”

Fritz Habicher’s letter to Josef’s widow informed her of the circumstances of her husband’s death. In early February 1945, Habicher, who had been forcibly conscripted, and four other SS soldiers were ordered to escort a convoy to the Dachau concentration camp made up of soldiers who had been sentenced to death for refusing to bear arms. The five guards were told that Josef Mayr-Nusser, one of the condemned, was a traitor who had abandoned his comrades in full battle. But Fritz was struck by Josef’s gentleness, his kindness, and his expressions of gratitude for the smallest favors, and suspected that Josef was not the traitor he was accused of being. At the train station in Danzig, the convicts were locked in a wagon and taken for ten days, with barely any food or drink, across a Germany in ruins. The train halted in Erlangen, near Nuremberg, because the tracks were too damaged to continue. Josef suffered from an edema due to hunger, and severe diarrhea. The prisoners were fed a little, but were not allowed to leave the wagon. After eight days, the officer in charge obtained authorization to transfer the sickest prisoners, including Josef, to barracks that had been converted into a hospital. They had to walk several kilometers across the city, and in the end Josef, completely spent, had to be carried by his comrades. After a long wait, the doctor sent him back to the wagon, telling him that his case was not serious, and to go to the hospital the next day. Josef accepted this assessment without protest. He was taken back to Erlangen station and thanked his comrades with a warm: “May God reward you for everything!” A few hours later, on the night of February 23-24, 1945, Josef died alone in the wagon, without the aid of a priest (which the SS had not thought necessary). Habicher found a New Testament, a missal, and a rosary next to Josef’s body, which made him certain that so exemplary a Christian would never have betrayed his comrades. He and the other SS soldiers buried him with military honors in the presence of a priest from Erlangen.

In 1947, an autopsy on the body confirmed the cause of death: Josef Mayr-Nusser “died of hunger.” In 1958, his body was brought back to Bolzano. He was re-buried in 1963, inside a newly built Lichtenstern church, dedicated to Saint Joseph. In 2005, a monument to his memory was erected. In giving the benediction, the Bishop of Bolzano-Bozen, Bishop Wilhelm Egger, declared, “Today we live in a so-called free society, yet there is an enormous, even coercive moral pressure which is difficult to escape on families and especially young people, encouraging sexual freedom, marital infidelity, divorce… Josef Mayr-Nusser offers us an example of being faithful to one’s conscience, regardless of the always shifting trends of the time. The ideals for which Nusser died—charity, faith, freedom—are the formative ideals families need.

He was the victor

Josef Mayr-Nusser was beatified in Bolzano on March 18, 2017, in a ceremony presided over by Cardinal Angelo Amato. The next day, during the Angelus message in St. Peter’s Square in Rome, Pope Francis said: “He died a martyr because he refused to adhere to Nazism out of fidelity to the gospel. Because of his great moral and spiritual intelligence, he constitutes a model for lay faithful.” For Bishop Ivo Muser, the current Bishop of Bolzano, “Josef Mayr-Nusser has a great deal to say to us and to our time. He is not just the person who refused to pledge his loyalty to Adolf Hitler; he is also someone who was strengthened by and lived out his Christian identity. I see in this brave and uncomfortable figure, who forces us to face a dark and painful chapter in our history, a credible and consistent witness of fidelity to one’s own conscience; a conscience that is aligned with the gospel and the teachings of the Church. Blessed Josef acted out of the biblical conviction that ‘we must obey God rather than men’ (Acts 5:29). Now, we can and must assert confidently: Josef Mayr-Nusser may have been vanquished by a system that was scornful and destructive of men, but in the eyes of God, he was the victor!”

Let us ask Blessed Josef to intercede on our behalf, that we may also have the courage to follow his example of perfect fidelity to the Lord.