July 24, 2024

Blessed Henri Planchat

Dear Friends,

“Have you ever come across a small priest in Paris with a reddish hat, a shabby cassock and holes in his shoes, who is very poor because he gives everything to the poor, and who only visits the rich to ask for alms; who, whatever the weather, roams the most remote suburbs, climbing into every garret, visiting the sick and helping the most abandoned?… Citizen, if you have come across such a priest, well, he is my son!” It was with these words that the mother of Henri Planchat, a priest detained in 1871 by the leaders of the Paris Commune, petitioned a judicial delegate for a pardon for her son. She had invented nothing, it was all true. The Church now honors this priest as a blessed and a martyr.

Marie-Mathieu Henri Planchat was born on November 8, 1823 in Bourbon-Vendée (now known as La Roche-sur-Yon, in western France), the eldest of four children. His father was a local court judge. The family loyalty to the Catholic faith was absolute: Henri’s grandfather had risked his life to hide fourteen priests during the dark days of the French Terreur (1792–94). Three of the Planchat children, Henri and his two sisters, embraced the religious life.

Marie-Mathieu Henri Planchat was born on November 8, 1823 in Bourbon-Vendée (now known as La Roche-sur-Yon, in western France), the eldest of four children. His father was a local court judge. The family loyalty to the Catholic faith was absolute: Henri’s grandfather had risked his life to hide fourteen priests during the dark days of the French Terreur (1792–94). Three of the Planchat children, Henri and his two sisters, embraced the religious life.

In 1832, the magistrate and his family moved to Lille, where Henri received First Holy Communion in 1835. From that moment on, he had a burning desire to receive Jesus in the Holy Eucharist; however, his confessor allowed him to do so far too rarely to his liking (at the time, the faithful’s admittance to Holy Communion was limited to certain days). He also experienced a great devotion to the Blessed Virgin.

In 1837, Henri entered the Collège Stanislas in Paris as a boarder. Although he did well at school, he struggled to adapt to boarding school life and became gloomy and taciturn. His father then placed him in the care of Fr. Poiloup, headmaster of the Collège de Vaugirard. After obtaining his baccalaureate in 1842, the young man was admitted to the Faculty of Law, remaining at Vaugirard as a monitor and tutor. His spiritual diary bears witness to the battles he waged against his fiery and proud temperament. At the same time, he had to fight against discouragement at his slowness in correcting his weaknesses: “The tree of my soul must bear fruit in patience. I must put up with my imperfections, not to the point of liking them, but without making them worse by being troubled and discouraged. Just as a seed sown in the earth grows imperceptibly, so does good grow but slowly in our souls.”

In 1843, Henri asked to enter the Parisian seminary of St Sulpice and was admitted to do so. But his father, who for political reasons had been relegated to the presidency of the court of Oran in Algeria, asked him to complete his law studies first; the young man believed he had to obey him. A layman by force, he joined the Society of St Vincent de Paul, where he learned about the harsh realities of poverty and how to alleviate them. He soon became a member of a group of Catholics who had recently opened an oratory in the Rue du Regard, where apprentices and young workers could find a place of Christian education and wholesome recreation.

In August 1847, Henri graduated in law and obtained his father’s permission to enter the seminary. Judge Planchat died in June 1848, and Henri left for Algiers for a few months to be near his mother and sister. On his return to Paris, he distinguished himself at the seminary by his spirit of poverty. In his diary, he wrote: “When you want to convert, you don’t go to confession to those who have fine clocks and beautiful rugs in their apartments… I shall avoid anything that smacks of elegance in my furnishings.” As his ordination to the priesthood approached, the young seminarist wrote to his mother: “I am happy, my happiness is growing every day, in the complete and irrevocable immolation of my whole being to the Lord.” He added: “For a long time now, grace has been calling me to the service of the poor, out of a spirit of faith. I firmly resolve never to lose a single opportunity to follow this impulse.” Yet he was wary of any agitation, even when caused by his zeal for good: “I may have imagined that I possessed charity, because I was inclined to agitation in good works. That is not true charity. Natural activity is the venom of charity. True charity is intimate to the soul; it envelops it, it penetrates it. Let its fire live in the depths of my soul, and my outward operations will be perfect!” On December 21, 1850, Father Planchat was ordained a priest.

Bringing the Workers Back to Christ

On March 3, 1845, a layman, Jean Léon Le Prévost (1803–1874), founded the association of the Brothers of St Vincent de Paul in Paris with two friends, Maurice Maignen and Clément Myionnet, with the aim of evangelizing the working classes. Made up entirely of lay brothers, it specialized in the development of oratories where workers would find hospitality and support in the harsh social context of economic liberalism that had emerged from the French Revolution of 1789. The founders’ intention was to bring the workers back to Jesus Christ and the Church. Three days after his ordination, Fr. Planchat joined this young congregation, humbly accepting submission, as a priest, to a lay superior. It was not until 1860 that Brother Le Prévost was ordained a priest; in 1869, the Holy See stipulated in the decree of approval: “The Institute must be priestly.”

The February 1848 revolution had revealed the pressing nature of the social question. Faced with a socialist movement that advocated the abolition of private property, lay Catholics (Armand de Melun, Blessed Frédéric Ozanam) were reflecting on ways to restore justice and humanity to social relations, while at the same time avoiding the risk of slipping from the liberal “law of the jungle” to socialist utopias that would destroy the natural order. Fr. Planchat began his apostolate in Grenelle, south-west of Paris. In 1850, because of the social crisis that had led to the closure of a great number of factories, 80 % of its 8,000 inhabitants were living in destitution; religious life was virtually non-existent. The Brothers of St Vincent de Paul settled there in 1847 and founded an oratory. In December 1850, the “Stove of St Vincent” provided the district’s destitute with an all but free soup kitchen.

From the moment he arrived, Fr. Planchat became a “soul hunter”, reaching out to the poor who were no longer churchgoers. No amount of misery or mockery could deter him. To washerwomen who insulted him, he responded by offering medals and images, so that these same women, seized with shame, gave him five francs, a large sum, to say Holy Masses. In August 1851, he fainted from exhaustion at the edge of the pavement. He was seriously ill and soon had to leave for Italy to restore his health. Before returning to Paris a year later, Pope Pius IX granted him a private audience and offered him his encouragement. In April 1853, Fr. Planchat resumed his apostolate in Grenelle, where he remained for eight years.

Henri knocked on every door, even those of the poorest hovels; he confessed and made converts, and regularized hundreds of marriages. He always went straight to the point, speaking of God, indifferent to the taunts attracted by his shabby greening cassock and frail appearance. His influence on souls can only be explained by his profound union with God. “A hundred words to God, for one to men” was his motto. But he did not work in isolation; he enlisted the help of local lay people, who in 1853 formed the “Association ouvrière de la Sainte-Famille” (Workers’ Association of the Holy Family), which had as its goal “mutual aid and support, but also the evangelization of workers by workers”. He soon became responsible for an oratory for young female workers.

Fr. Planchat provided assistance to both bodies and souls, giving of himself without counting the cost. One very cold day, he returned to the community in his bare feet, to the outrage of the caretaker. The offender apologized to her, explaining: “I gave my shoes to a poor man who had none, on the esplanade of the Invalides. What can I say, but that he was older than I!” His saintliness irritated the established clergy. In 1861, the parish priest of Grenelle started a slanderous campaign against him out of jealousy. Fr. Planchat’s superiors were forced to move him away from Paris and sent him to Arras to take over as sub-director of an educational establishment for orphans and apprentices. He stayed there for two years, encouraging the boarders to receive Holy Communion often.

A Pressing Appeal

Over the centuries, lay Christians had slowly become estranged from frequent Communion, contenting themselves with receiving Communion on the major holidays. In the 17th century, the Jansenist heresy even contended that sacramental communion should be the privilege of a small number of the most perfect members of the faithful. However, many saints argued in favor of frequent Communion. This spiritual movement culminated in the publication, at the behest of Pope St Pius X, of the decree Sacra Tridentina (December 20, 1905). Referring to a directive of the Council of Trent, the decree states:

“I. Frequent and daily Communion, as a practice most earnestly desired by Christ our Lord and by the Catholic Church, should be open to all the faithful, (…) so that no one who is in the state of grace, and who approaches the Holy Table with a right and devout intention can be prohibited therefrom.

“II. A right intention consists in this: that he who approaches the Holy Table should do so, not out of routine, or vain glory, (…) but that he wish to please God, to be more closely united with Him by charity, and to have recourse to this divine remedy for his weakness and defects.”

The Catechism of the Catholic Church specifies: “The Lord addresses an invitation to us, urging us to receive him in the sacrament of the Eucharist: Truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of man and drink his blood, you have no life in you.” (Jn 6:54)… “The Church strongly encourages the faithful to receive the holy Eucharist on Sundays and feast days, or more often still, even daily.” However, quoting the apostle St Paul (1 Cor 11:27-29), the Catechism reminds us that “anyone conscious of a grave sin must receive the sacrament of Reconciliation before coming to Communion” (nos 1384, 1385, 1389).

The Three Pillars

Returning to Paris in 1863, Fr. Planchat was soon placed in charge of the Sainte-Anne oratory in Charonne, a working-class neighborhood in the 20th arrondissement. Due to personal conflicts, he was unable to live there until 1870, but had to return every day to sleep in Vaugirard, at the other edge of Paris. It was not long before five hundred young apprentices and workers were coming to Sainte-Anne in search of wholesome distractions and the means to lead a truly Christian life. The Father built a chapel, which was blessed in 1867, as well as a home for apprentices without families, who lived there permanently. His method was based on three pillars: religious instruction, the reception of the sacrament of Penance and frequent Eucharistic Communion. He believed that it was up to each spiritual father to determine whether the children under his guidance were in a condition to receive frequent Communion. On Sundays, he was always available in the confessional as early as six o’clock in the morning, and other priests would come to help him so that everyone could go to confession before High Mass.

Fr. Planchat believed in the sanctifying virtue of the Blessed Sacrament and of Holy Communion to protect his young men from harmful influence. Before long, he set up the “Work of First Communion for late-comers” for the benefit of adolescent and adult workers. He strove to make it easier for these young workers who were already in the factory or workshop to prepare themselves doctrinally and spiritually for Communion. This enabled him, three or four times a year, to lead a hundred or so people of all ages to the Holy Table for the first time, after a three-day retreat at the expense of the oratory. In order to encourage the perseverance of adult men who all too often abandoned their religious practice, he also organized retreats for fathers.

“By the same charity that it enkindles in us, the Eucharist preserves us from future mortal sins. The more we share the life of Christ and progress in his friendship, the more difficult it is to break away from him by mortal sin. The Eucharist is not ordered to the forgiveness of mortal sins—that is proper to the sacrament of Reconciliation. The Eucharist is properly the sacrament of those who are in full communion with the Church” (CCC 1395).

Charonne was home at that time to many Italians who had come to Paris in search of work, but who as yet had no knowledge of French. Fr. Planchat organized retreats for them in Italian, preached by a religious from their country; at the final ceremony, each participant received a scapular of Mount Carmel. He was not content with attracting just two hundred participants to each retreat: he reckoned that there were 20,000 Italian workers in Paris, most of whom did not practice their religion. He therefore founded an Italian “Holy Family” in Charonne, which was to serve as a model for several others established in different districts. This Catholic ministry for Italians continued long after the death of its founder.

In the Besieged City

At the beginning of 1870, the Sainte-Anne patronage was at its most flourishing: four hundred apprentices and workers attended regularly and more than five hundred former members remained in touch with him. The Charonne district was being transformed by the work of the Centre, which was now staffed day and night by religious workers. But September 2 brought the news of the French military disaster at Sedan. On the 19th, the Prussian army besieged Paris, and was to remain there for four months. Parisian workers and their families were reduced to joblessness as trade and industry ground to a halt. Soon they were gripped by hunger. Fr. Planchat went from door to door looking for food and managed to collect enough money to maintain an open table despite the extortionate price of food. Not long after, he created an ambulance in Sainte-Anne that took in hundreds of war victims. He provided thousands of soldiers, left idle in the besieged city, with the necessities of body and soul. He went to the front lines every day to help the wounded and offer the last rites to the most severely wounded. On February 7, 1871, the patronage was attended by 8,000 soldiers, 5,000 of whom received Holy Communion after going to confession. Its popularity displeased the socialist and anarchist leaders. A commanding officer ordered the Father, “in his own interest”, to stop distracting soldiers from their military duties by luring them to the patronage, which was a false accusation. Fully committed to his ministry, Fr. Planchat did not seek to protect himself.

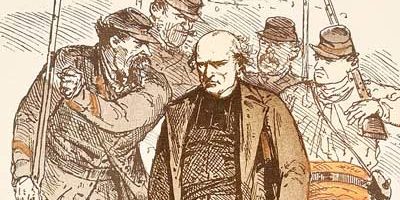

On March 18, 1871, the uprising of the Paris Commune broke out against the regular government presided over by Adolphe Thiers, who had fled to Versailles. The “federates”—socialists, communists and anarchists—established a dictatorship in the capital. Paris had fallen into the hands of extremist factions. Churches were desecrated amid an outburst of anti-religious hatred fueled by the press. On Maundy Thursday, April 6, 1871, a group of federates entered Sainte-Anne, looking for Fr. de Broglie, whose brother was a member of the National Assembly in Versailles. When they failed to find this priest (whom Henri Planchat had ordered to go somewhere safe), a commissaire, revolver in hand, notified to “citizen Planchat” that he was under arrest. They took him to the town hall in the 20th arrondissement, where he was questioned. On Good Friday, he was transferred to the Police Headquarters, where he spent Easter in a miserable, tiny cell. On April 13, he was taken to the Mazas prison where twenty-five clergymen were already being held hostage, including Archbishop Darboy of Paris. The prisoners would remain there for thirty-nine days in individual cells, with no possibility of celebrating Mass. The populace was inflamed because of the repeated failure of the Communards and was hunting for “traitors” on whom to take revenge.

When the local community in Charonne learned of Fr. Planchat’s shocking arrest, they took action. A petition was organized and collected over three hundred signatures: “We certify that M. Planchat is incapable of harming the government, whichever it may be. In our neighborhood, he is the succor to our miseries; we miss his inexhaustible charity, especially in our present situation. We therefore ask the committee to release this citizen who has been known and honored in the neighborhood for so many years.” The petition remained unanswered, but the prisoner was provided with food until the end by the parishioners of Charonne, at their own great risk.However, Fr. Planchat’s health was deteriorating; he slept badly and “felt irritation and inflammation gripping his nerves”, especially when thinking of his abandoned apprentices.

Strike the Priests First!

On May 21, the “Versaillais” entered Paris by surprise; it would take them a week to gain control of the entire city. From that moment there were no bounds to the violence. Rigault, the Commune’s public prosecutor, cried out: “We have hostages, and among them are priests: let’s strike them first!” On May 22, fifty-four prisoners from Mazas were transferred to the prison of La Roquette. For a moment, they were all together, and were able to confess and receive Holy Communion, as the Jesuits had the Blessed Sacrament with them.

“In addition to the Anointing of the Sick, the Church offers those who are about to leave this life the Eucharist as viaticum. Communion in the Body and Blood of Christ, received at this moment of ‘passing over’ to the Father, has a particular significance and importance. It is the seed of eternal life and the power of resurrection, according to the words of the Lord: He who eats My flesh and drinks My blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up at the last day (Jn 6:55)” (CCC 1524).

On May 24, a mob headed by women broke into the prison of La Roquette and seized six hostages, including Archbishop Darboy and four priests who had been picked at random. They were shot dead in full view of the other prisoners. On the 25th, five Dominicans from the convent of Arcueil were shot dead on the Avenue d’Italie, along with eight staff members of their college. Fr. Planchat devoted all his time to hearing the prisoners’ confessions. On the afternoon of May 26, he was removed from the prison, along with nine other clergymen and some forty civilians, by “colonel” Émile Gois. The convoy passed through Belleville; on the way, voices from the frenzied crowd hurled insults at the hostages, demanding their lives. One witness later remembered: “Fr. Planchat was walking with his eyes downcast, in profound recollection, no doubt thinking only of making a sacrifice of his life to God.” At about 6 o’clock, when the prisoners reached the Rue Haxo, the assembled mob struck them and shoved them towards the low wall of a vacant lot in front of which they were lined up.

Fr. Planchat begged that fathers of children be spared, and offered to die himself in their place. Some of the Communard leaders were reluctant to give the irrevocable command. Then, out of the blue, a revolver shot rang out, followed by haphazard shooting; the carnage lasted half an hour, with rifle and revolver shots and the wielding of bayonets. The assassins loaded and fired again and again. According to several witnesses, Fr. Planchat died on his knees, praying unto his dying breath. Not one of the fifty hostages survived. “It appears not to have been an organized execution, but a form of mass lynching”, the historian Robert Tombs later explained.

Henri Planchat, the “Apostle of Charonne”, was recognized as a martyr by Pope Francis and proclaimed Blessed in the church of St Sulpice on April 22, 2023, along with four religious from the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary (known as “the Picpus”), who, like himself, were victims of the massacre of the Rue Haxo. Through Fr. Planchat’s intercession, we can ask God for the grace to become missionaries of the Eucharist, this Sacrament of love of which Jesus said: The bread that I will give is My flesh, for the life of the world (Jn 6:52). May Blessed Henri also help us, following his example, to devote ourselves to the service of the poor and the suffering whom God places in our path. As long as you did it to one of these My least brethren, you did it to Me (Mt 25:40).