October 23, 2016

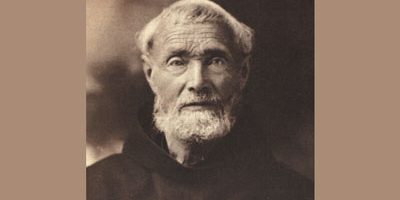

Blessed Frederic Janssoone

Dear Friends,

While leading a Way of the Cross at World Youth Day in Rio de Janeiro (Brazil), Pope Francis emphasized, “The Cross of Christ contains all the love of God; there we find His immeasurable mercy. This is a love in which we can place all our trust, in which we can believe… Let us entrust ourselves to Jesus, let us give ourselves over to him, because he never disappoints anyone! Only in Christ crucified and risen can we find salvation and redemption.”

The Cross of Christ was the great mystery preached by Blessed Frederic Janssoone, a great apostle of the 19th century whose zeal was exercised on three continents. He was born on November 19, 1838 in Ghyvelde, a Flemish village near Dunkirk, in the extreme north of France. His father, Pierre-Antoine, was a modest farmer with typical Flemish values: respect for work well done, the sense of family, a simple and robust faith. His mother, Marie-Isabelle, was an excellent wife, wise mother, and a passionate Christian, who gave birth to thirteen children from two successive marriages; she consecrated all her children to the Blessed Virgin and fervently longed for her sons to become priests. In this harmonious home, they prayed together, reciting the Rosary while meditating on the mysteries of the life of Jesus, inserting the name of the mystery into each “Ave Maria”. Frederic used to recount that one day, after having heard passages read from the life of the Desert Fathers, the four youngest children decided to become hermits and disappeared. That night, they were found praying behind a haystack! The Janssoone family was well-known for their charity to the poor, who would find shelter and welcome at their house. The Archbishop of Cambrai, having met the family during a pastoral visit, admitted, “I did not think that such a profoundly devoted Christian family still existed in our day.” Struck with stomach cancer, Pierre-Antoine Janssoone left this world in 1848, whispering to his family: “May the Good God keep you!”

The Cross of Christ was the great mystery preached by Blessed Frederic Janssoone, a great apostle of the 19th century whose zeal was exercised on three continents. He was born on November 19, 1838 in Ghyvelde, a Flemish village near Dunkirk, in the extreme north of France. His father, Pierre-Antoine, was a modest farmer with typical Flemish values: respect for work well done, the sense of family, a simple and robust faith. His mother, Marie-Isabelle, was an excellent wife, wise mother, and a passionate Christian, who gave birth to thirteen children from two successive marriages; she consecrated all her children to the Blessed Virgin and fervently longed for her sons to become priests. In this harmonious home, they prayed together, reciting the Rosary while meditating on the mysteries of the life of Jesus, inserting the name of the mystery into each “Ave Maria”. Frederic used to recount that one day, after having heard passages read from the life of the Desert Fathers, the four youngest children decided to become hermits and disappeared. That night, they were found praying behind a haystack! The Janssoone family was well-known for their charity to the poor, who would find shelter and welcome at their house. The Archbishop of Cambrai, having met the family during a pastoral visit, admitted, “I did not think that such a profoundly devoted Christian family still existed in our day.” Struck with stomach cancer, Pierre-Antoine Janssoone left this world in 1848, whispering to his family: “May the Good God keep you!”

Frederic was only ten years old and first in his class in primary school when he told his mother of his desire to become a priest. Peter, the eldest of the family, had just entered the seminary. The studies were expensive, but Marie-Isabelle did not hesitate: it was worth the sacrifice to make this dream come true. Frederic began his high school studies brilliantly, but they were soon ended by misfortune: his mother fell ill. Frederic had to leave school to find work; his brother Peter also left the seminary for health reasons. The two brothers found work with a fabric merchant in Estaires. Frederic began modestly as an errand boy, but his ability earned him a quick promotion. He viewed his professional future optimistically and even dreamt of marrying his boss’ daughter.

Under the Franciscan habit

Following the death of his mother in 1861, he resumed his studies alongside his work. Madame Janssoone took with her to heaven a still lively desire to have one or more priests among her sons (one of her daughters was already a religious sister). Peter entered the Foreign Missions, and served as a missionary for forty-two years in India, where he died in the odor of sanctity in 1912. Another son, Henry, joined the Franciscans, and died by drowning in 1867. At the time, Frederick no longer thought of God’s call; but the death of his mother, who he knew had made an offering of herself to the Lord, led him to return to his own total consecration. He knocked on the door of the Cistercian Abbey of Mont-des-Cats, but the Abbot, unnerved by his worldly manners, turned him down. Frederick then looked to the Franciscans. He entered their convent in Amiens in June 1864 and soon received the brown habit. Life in the novitiate was austere—the winter cold severe and the poverty very real. After overcoming a period of doubts about his vocation, he pronounced his vows on July 18, 1865. He began his studies in Limoges and continued them in Bourges, where he was ordained in 1870 at the age of thirty-two.

France declared war on Prussia. Father Frederick was mobilised as chaplain of a military hospital established in the convent of the Sisters of the Sacred Heart in Bourges; there, he helped many soldiers who were wounded or stricken with typhus to be reconciled with the Lord. When hostilities ended in 1871, he was sent to Bordeaux, to a newly founded monastery, where he soon was made superior. He excelled in organizing many religious celebrations. In particular, on August 2nd, the day of the indulgence of the Portiuncula, granted to the faithful who devoutly visit a Franciscan church (the Portiuncula in Assisi is the place that St. Francis loved most in the world, because, in this small church, he received the assurance that his sins had been forgiven), he gathered 25,000 people around the shrine of Our Lady of the Angels. Up till his death, Father Frederic made the feast of August 2nd a great celebration of salvation. But he was not cut out to be a superior, and in 1873, he was discharged from this burden that was crushing him in order to preach parish missions. These “domestic missions” were to be a “new evangelization” of Christians who had forgotten their religious duties. However, in 1876, Father sought and obtained permission to be sent to the Holy Land for six years. Since 1342, the Church has entrusted the Franciscans “custody” of the Holy Land, that is, the mission to maintain and welcome pilgrims to the places sanctified by the life and Passion of Christ. Over the centuries, 6,000 Franciscans have been sent there, of whom 2,000 irrigated the Holy Land with their blood. Upon his arrival in Jerusalem, Father Frederic began by making a four month long retreat at the convent of the Holy Sepulchre, the very place where Jesus was buried and rose again.

Artisan of peace

In 1878, he was appointed Custodial Vicar, that is, the senior assistant to the superior of the Franciscans of the Holy Land. The Vicar has three roles: a diplomatic role on behalf of France; the duty of providing spiritual services for the French-speaking communities there; and an administrative role to oversee the construction and maintenance of Catholic convents and churches. In that last role, Father Frederic had the Church of St. Catherine of Bethlehem built, to compensate for the loss of the Church of the Nativity, occupied by the Orthodox since the 18th century. This church was completed in 1882, after lengthy negotiations with the Orthodox bishop, the Turkish pasha and the consul of France. Father Frederic also built the Church of the Holy Savior in Jerusalem.

In 1881, the anti-clerical French government decreed the expulsion of 5,000 monks and nuns belonging to unauthorised religious congregations. This measure proved to be a severe blow to Catholic missions supported by France. In August of that year, Father Frederic sailed to Canada to preach on behalf of the Holy Land missions. There he fell gravely ill, a victim of the Quebec winter. Upon recovery, he returned to Palestine in June 1882. He faced the need to pacify sometimes bloody conflicts among Christians of various denominations (Catholics, and Orthodox divided into various national patriarchates) with respect to the use of the Basilica of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem and the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. In a spirit of broad consultation with representatives of various Churches, Father Frederic applied himself to writing down regulations that previously had existed only in oral form. To that end, with the aid of a Friar, he had the customs existing in the sanctuaries minutely observed day and night, and wrote two books of 500 and 300 pages, devoted to the customs of the Holy Sepulchre and of Bethlehem respectively. These regulations are still in force today. During his innumerable travels in the Holy Land, Father Frederick also acquired a perfect knowledge of the history of the Holy Places. He took care of Catholic pilgrims during their stay in what was at the time a rough and primitive land. For them, he built the hostelry Our Lady of France and organised retreats there. In 1884, he welcomed his own brother there, who was a missionary.

A path of compassion

Since the 14th century, the Franciscans of the Holy Land have had the practice on Fridays of accompanying pilgrims along the Via Dolorosa, the route followed by Jesus during His Passion from Pilate’s court to Golgotha and the Holy Sepulchre, praying along the path where the Lord had suffered and given His life. This practice is the origin of the devotion of the Way of the Cross, spread throughout Christendom by the Franciscans. In the 17th century, the number of Stations in the Way of the Cross was fixed at fourteen. In the first half of the 18th century, St. Leonard of Port Maurice, an Italian Franciscan, was known as one of the major promoters of this devotion. In 1878, Father Janssoone discreetly restored this practice in Jerusalem; soon after, the Ottoman political authority granted him the privilege to officially preach in public on Good Friday. Many pilgrims regarded his sermons as the high point of their pilgrimage. Since then, each week the Franciscans have led the Way of the Cross down the “Via Dolorosa” in the Old City of Jerusalem.

Opening wide the spiritual treasure held by the Church—a treasure made up of the infinite merits of the Saviour and the superabundant merits of the Virgin Mary and the saints—the Church grants a plenary indulgence to all the faithful who practice the Way of the Cross devotion (or, if unable to, unite with the one conducted by the Pope, or broadcast on television or radio, or meditate on the Passion for fifteen minutes). The Way of the Cross is a way of compassion with the sufferings of Christ, and it is a way of conversion which encompasses the recognition of our sins, the true cause of the suffering and death of Jesus on the Cross, and asks pardon of God the Father. The devotion is arranged around two pillars: the contemplation of scenes of the Passion, and its corollary: our walk in the footsteps of Christ in our daily life, following the Virgin. Tradition tells us that Mary was the first to walk the path followed by her Son to Calvary. Each of the fourteen stations consists of meditation on a moment of the Via Dolorosa (not always mentioned in the Gospel, such as the encounter with St. Veronica), supplemented by a prayer and singing of a verse of the Stabat Mater or another suitable hymn.

Birth of a sanctuary

Asked to return to Canada by many priests who had not forgotten his first visit, in April 1888 Father Frederic was made, by a papal brief, the Holy Land Commissioner of Canada. His mission was to find the necessary resources for the safe keeping and better functioning of the Holy Places in Palestine. To that end, he would preach, collect offerings and organise pilgrimages. As soon as Father Frederic arrived in Trois-Rivières, a city located between Montreal and Quebec, he was invited to preach at the consecration to Our Lady of the Rosary of a small church, built in 1720 in Cap de la Madeleine, on the bank of the Saint Lawrence River. On June 22, 1888, he enthroned a statue of Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal in this church, and prophesied that “Our Lady of the Cape” would become the primary Marian shrine in Canada. That same evening, around 7:00 pm, three men entered the church to pray: Father Frederic, Father Désilets, the parish priest, and Pierre Lacroix, a disabled man. They suddenly saw the eyes of the statue, which are normally lowered, open wide. The Virgin looked straight ahead with an expression of severity mixed with sadness. This miracle lasted five to ten minutes. From that day on, Father Frederic became a tireless apostle of pilgrimage to Our Lady of the Cape, which he would make known everywhere during his travels and through the magazine “Annals of the Most Holy Rosary”. The growing number by pilgrims justified, in 1897, the construction of a deep water dock and a railway branch to the sanctuary. In 1902, burdened by too many tasks, Father Frédéric entrusted the sanctuary to the Oblates of Mary Immaculate; two years later, the Holy See granted the statue of Our Lady of the Cape the rare privilege of “coronation”. During the ceremony, it fell to Father Frederic to carry the crown, which the bishop placed on the forehead of the statue as a sign of Mary’s spiritual royalty. In 1955 the Oblates began the construction of an imposing basilica beside the original small chapel to accommodate the faithful. It was completed in 1964.

The apostolate of Father Frederic in Quebec, where he spent twenty-eight years, reached out to other places as well. He generously devoted himself to the service of his adopted homeland as a preacher, itinerant missionary and journalist. From parish to parish, he preached the great truths of the faith, particularly the “four last things”—death, judgment, heaven, and hell—of which the Pope Paul VI said: “One of the fundamental principles of the Christian life is that it must be lived in the light of its eschatological destiny, future and eternal. Yes, it makes one tremble. The prophetic voice of St. Paul still warns us: Work out your own salvation with fear and trembling (Phil. 2, 12). The gravity and uncertainty of our final fate have always been a rich subject of meditation and a source of unparalleled energy for morality and holiness in the Christian life” (April 28, 1971). The same Pope also remarked: “Our final ends are spoken of rarely and little. But the Council reminds us of the solemn eschatological truths that concern us, including the terrible truth of the possible eternal punishment that we call Hell, of which Christ openly speaks of (cf. Mt. 22:13; Mt. 25:41; Lumen Gentium, 48)” (September 8, 1971). Moved by Father Frederic’s strong and simple eloquence, many of the faithful sought to confess their sins. To hear them all, an “army” of priests would accompany him. As to the stunning favors received by those who asked for his prayers, Father attributed them all to the intercession of Our Lady of the Cape, and to the relics he had brought from the Holy Land.

Fruitful trips

A true Franciscan, Father Frederic practiced the strictest poverty, not only eliminating the unnecessary, but even allowing necessary things sparingly. As a fundraiser, large sums of money passed through his hands; but his clothes, his food, his furnishings, all reflected great detachment. As an itinerant missionary, he adopted a rhythm of life that would have exhausted a man of far more robust health than his. The urgency to evangelise souls to save them from perdition was obvious for him. St. Paul’s words echoed in his heart: Woe is unto me, if I preach not the gospel… For the love of Christ compels us (1 Cor. 9:16; 2 Cor. 5:14). He never missed the opportunity to preach at St. Anne de Beaupré and Saint Joseph’s Oratory, built by St. (Brother) André in Montreal. He made use of his boat journeys on the St. Lawrence River—twenty-four hours from Trois-Rivières to Montreal, and thirty-six hours from Trois-Rivières to Beaupré near Quebec—to preach to the passengers. A witness who heard him speak for four hours straight said that no one had gotten tired of it. Father Frédéric also built three “Ways of the Cross” to develop this devotion in Canada.

On Good Friday 2005, a few days before the death of John Paul II, Cardinal Ratzinger preached the Way of the Cross at the Coliseum. By way of introduction, he explained the meaning of this devotion: “The prayer of the Way of the Cross is a path leading to a deep spiritual communion with Jesus; lacking this, our sacramental communion would remain empty. This vision contrasts with a purely sentimental approach to the Way of the Cross. In the 8th Station our Lord speaks of this danger to the women of Jerusalem who weep for him. Mere sentiment is never enough; the Way of the Cross ought to be a school of faith, the faith which by its very nature ‘works through love’ (Gal. 5:6). This is not to say that sentiment does not have its proper place. … In the Way of the Cross we see a God who shares in human sufferings, a God whose love does not remain aloof and distant, but comes into our midst, even enduring death on a cross (cf. Phil. 2:8). The God who shares our sufferings, the God who became man in order to bear our cross, wants to transform our hearts of stone; He invites us to share in the sufferings of others. He wants to give us a ‘heart of flesh’ which will not remain stony before the suffering of others, but can be touched and led to the love which heals and restores…

“We also see more clearly the meaning of the words…: If any man would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me (Matt. 16:24). Jesus himself interpreted for us the meaning of the Way of the Cross; He taught us how to pray it and follow it: the Way of the Cross is the path of self-denial, the path of true love. On this path He has gone before us…” On Good Friday, 2013, the Pope Francis remarked that the Way of the Cross helps us decide for (or against) Jesus: “The Cross is also a judgment: God judges us while loving us. If I welcome His love I am saved, if I refuse it I am condemned, not by Him but by myself, because God does not condemn, He only loves and saves” (March 29, 2013).

Door-to-door preacher

Father Frederic used all forms of the media to reach the public at large with the Good News. Until the end of his life, he also went ‘door-to-door’ to raise funds, to sell pious books, and above all to bring the Gospel to souls. At the age of seventy-two, he spend an entire month going door-to-door twelve hours a day. Nights, he frequently used desperately needed sleep time to engage in the apostolate of writing. He published, in a simple and popular style, countless articles, as well as over thirty books and brochures, in particular a life of Our Lord Jesus-Christ and a biography of St. Francis, which became best-sellers in Canada in their time. But the book he liked best was Heaven, Abode of the Elect.

Even though he was able to hide it with his drive and exceptional endurance, Father Frederic had poor health. He confided to a close friend that he had continual stomach pains that made eating almost impossible. His rest was his apostolic work; he always ended a parish mission in better shape than he started. In 1916, he collapsed during a pilgrimage; the diagnosis was advanced stomach cancer. During his fifty days of hospitalisation in Montreal, assailed by temptations of despair and other diabolical vexations, he was comforted by the sacrament of Extreme Unction which, as explained by the Catechism of the Catholic Church, “strengthens against the temptations of the evil one, the temptation to discouragement and anguish in the face of death” (CCC 1520). Father Frederic died on August 4, 1916. His tomb is in the Franciscan church in Trois-Rivières. He was beatified by Saint John Paul II on September 25, 1988.

Let us ask this ardent apostle of the Cross to help us to recognize the truth of the words Pope Francis said on July 26, 2013: “What has the Cross given to those who have gazed upon it and to those who have touched it? What has the Cross left in each one of us? You see, it gives us a treasure that no one else can give: the certainty of the faithful love which God has for us!”